Birch and gorse - October on the heath.

… Where are the songs of spring? Ay, Where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,—

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

John Keats, To Autumn (extract)

Sweet chestnuts in the churchyard at Crostwight, Norfolk.

Happy new moon in Libra!

In this issue of Bracken & Wrack:

Bats in the Belfry

Upon the Wing of a Swan

There’s Rosemary

The Goose Summers of the Autumn Saints

Saint Luke’s Apple and Ginger Crumble

Poems by John Keats, Hilary Llewellyn-Williams and Dylan Thomas

Bats in the Belfry

It’s not just the ruined abbey that invites nature to skip into the dance of its crumbling stones. Many a church still in use today is home to beautiful, wild, uninvited guests. Bats. One of our most magical and misunderstood mammals. The phrase ‘bats in the belfry’ means just that, and I have stepped through dusty porch after dusty porch into a space where I know bats to be sleeping high above my head.

I wonder why bats are held to be sinister? Is it their mysterious society; their night flight; their leathery wings? True, it can be disconcerting on a warm summer’s night to suddenly feel a shift in the currents as a bat skims your hair. But exhilarating too, to momentarily feel part of a world which so intimately knows both the barrow-field and the broken stone archway.

Perhaps it’s because bats have ‘dark’ wings in contrast to the ‘light’ ones of cherubs and angels? I have seen many a gravestone carved with bat-winged hourglass or skull. Likewise the gargoyles, imps and demons that stare from corbels and the underside of fonts. It goes without saying that their dark lord is similarly endowed.

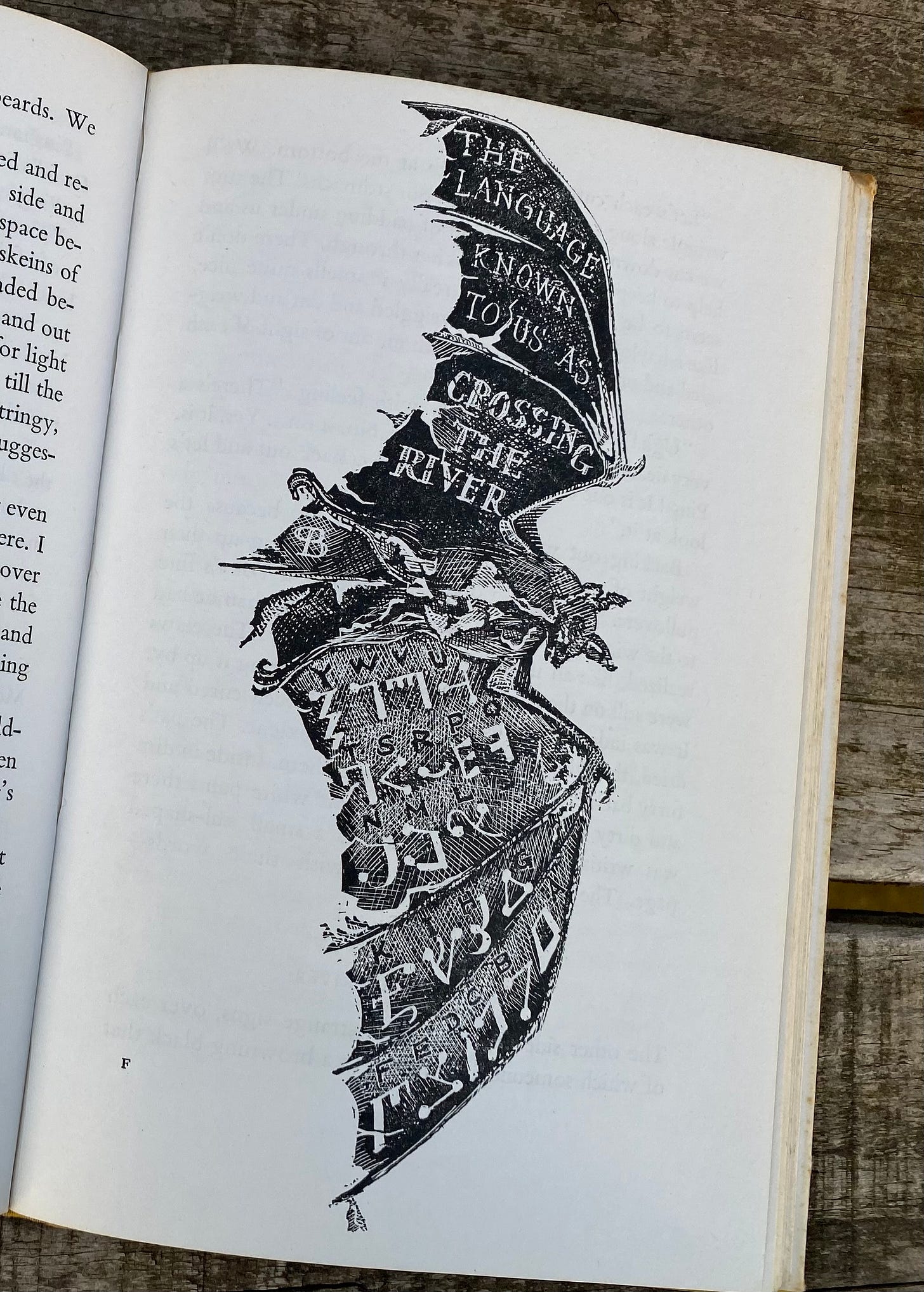

I don’t know whether it’s this that led bats to be linked with witches and held to be their familiars, or whether it’s the other way around. But the association is definitely there. And witches are known to haunt churchyard and lichened standing stone alike; anywhere in the landscape where power can be sensed and gathered. In Lucy Boston’s ‘An Enemy At Green Knowe’, Tolly and Ping find a mummified bat with a witches alphabet scribed on one wing and ‘The Language Known To Us As Crossing The River’ on the other.

I once left a camera in a medieval church overnight, set to take a photo every hour from dusk to dawn. How exciting it would be to take the film into the darkroom not knowing what it had witnessed! I got permission to set up my tripod one summer evening and went home to try to sleep.

Sadly, nothing dramatic showed up in my grainy photos. No nocturnal goings-on of any kind. But - the anticipation! There was a beauty, too, in seeing the light gradually fading and rising over the crooked rows of chairs.

And how many times has it done that, before and since?

Upon the Wing of a Swan

Added to the natural significance of these birds is the possibility that they may also be regarded as spirit helpers imbued with supernatural qualities, being able to fly to the Upper World, dive through the water to the Lower World and exist on land in the Middle World.

Jill Cook, Ice Age Art (British Museum exhibition catalogue)

Around 6000 years ago in Bronze Age Denmark, an 18-year-old girl died. She was buried tenderly, curled on her side like an unborn child. But this young woman was herself a mother. Her newborn baby lay beside her in the grave, nestled upon the wing of a swan.

A story-snatch, swansdown floating through our outstretched fingers.

Throughout his life, the artist Joseph Beuys was fascinated by swans. From his childhood bedroom window he could see a large golden swan that sat atop the tower of Schwanenburg (Swan Castle) in his home town of Cleves. He painted swans often, seeing them as mediators between states of being, and between realms. In Schwanger und Schwan (Pregnant Woman and Swan), a tiny swan swims serenely inside the woman, replacing her unborn baby. Did you notice the similarity between these German words? My heart turned over.

Millennia before this - at least 25,000 years ago - at Ma’lta in Siberia, on the shores of Lake Baikal, people honoured their dead with beautiful mammoth ivory carvings. Discovered among them were 13 pierced pendants, interpreted as flying swans. Wings strong and sure, necks outstretched, what better companions on the journey to the afterlife? After all, we know that swans chart their migratory passage by the patterns in the stars.

Who knows what rites may have accompanied the start of these final journeys?

25,000 year old flying swan pendants from the shores of Lake Baikal in Siberia.

In early bereavement I found myself in the company of a pair of swans, who would fly in daily as I sat with my cafetière on the jetty at the lake. Once, I unearthed the thin sliver of pearl I later discovered to be a swan mussel. I thought of the day we had sat together on the grassy rampart of a Norfolk Iron Age fort. My beloved was sick. I scanned the skies for a sign, a clue from the ancestors. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a pair of swans flew directly over the monument.

Another moment and they were gone. Gone from sight, perhaps, but surely their wingbeats echo there still?

Swan mussel found at my special lake: Booton Clay Pit, Norfolk.

In the dawn fields, white fogs are breathing,

making a Chinese landscape -

the Nine Kings of the North Pole descend.

Cattle shifting in the near distance

sidle away from winter:

step by step, it has surrounded them.

The trees look thinner in this long sun:

drawing their juice in, they

contemplate dark traceries of mould.

Brown and gold brushstrokes over the hills.

A smell of frost and wood fires:

ivy increasing as the leaves fall.

Flowering ivy for the late bees

full blown and glossy, tightens

its massive grip, defies the cold Kings,

keeping slow but certain purposes:

enveloping the whole world

in patterned mounds of vegetation.

Here is a ruined cottage, sprouting

leaves, snake-stemmed and rustling:

part of the woods now, splitting apart.

The roof gone, how can the structure stand?

Ivy has loosened its knots.

Stone by stone, it is undone again.

From a roost above the fallen hearth

an owl calls in full daylight:

the Nine Kings of the North Pole descend.

But they step down from whatever heights

they journeyed in, with keen joy,

trailing blue air, a ripened sun.

There is a large fruit, still uneaten.

Look through a crack in the door.

Nine Kings treading ivy on the floor.

Hilary Llewellyn-Williams, ‘Ivy (30 September - 27 October)’ from The Tree Calendar

The approach of frost on the heath. 11 October 2022.

There’s Rosemary

Arthur Hughes, Ophelia, 1852.

Ophelia: There’s Rosemary. That’s for remembrance.

Pray you, love, remember.

(William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 5)

Fanned against the old churchyard wall stands a rosemary bush, its topmost branches almost peeping over the capstones. On warm days, its spicy incense floats over the path to the south porch. A pinch between thumb and forefinger releases its aromatic oils even on a chill twilit afternoon in late October.

From the time of its introduction by the Romans who used it in their funerary rites, rosemary has been prized for the remedial properties of these oils. Its fragrance was believed to preserve bodies and there was a fashion to plant it around tombs, the lasting green of its leaves making it a symbol of immortality. This memory persists, and sprigs of rosemary are often carried in funeral processions and thrown onto a coffin before the grave is filled.

In the language of flowers, rosemary stands for love, fidelity, remembrance and friendship. This makes the plant a beautiful expression of our feelings about dear ones who have passed from this world to the next. Indeed, rosemary has such a deep folk association with graveyards and funerals that just the sight of it growing can help us to remember friends and family who have died.

When used in aromatherapy, rosemary helps to reduce stress levels and nervous tension, boost mental activity, encourage clarity and insight, relieve fatigue, and support respiratory function. It’s also used to improve alertness, banish negativity and increase the retention of information by enhancing concentration.

Those little drops of oil have so many more qualities than ‘just’ helping us to remember.

But then again, perhaps there is no greater work they can do.

Rosemary in Crostwight churchyard.

It was my thirtieth year to heaven

Woke to my hearing from harbour and neighbour wood

And the mussel pooled and the heron

Priested shore

The morning beckon

With water praying and call of seagull and rook

And the knock of sailing boats on the net webbed wall

Myself to set foot

That second

In the still sleeping town and set forth.

My birthday began with the water-

Birds and the birds of the winged trees flying my name

Above the farms and the white horses

And I rose

In rainy autumn

And walked abroad in a shower of all my days.

High tide and the heron dived when I took the road

Over the border

And the gates

Of the town closed as the town awoke.

A springful of larks in a rolling

Cloud and the roadside bushes brimming with whistling

Blackbirds and the sun of October

Summery

On the hill's shoulder,

Here were fond climates and sweet singers suddenly

Come in the morning where I wandered and listened

To the rain wringing

Wind blow cold

In the wood faraway under me.

Pale rain over the dwindling harbour

And over the sea-wet church the size of a snail

With its horns through mist and the castle

Brown as owls

But all the gardens

Of spring and summer were blooming in the tall tales

Beyond the border

And under the lark full cloud.

There could I marvel

My birthday

Away but the weather turned around.

It turned away from the blithe country

And down the other air and the blue altered sky

Streamed again a wonder of summer

With apples

Pears and red currants

And I saw in the turning so clearly a child's

Forgotten mornings

When he walked with his mother

Through the parables

Of sun light

And the legends of the green chapels.

And the twice told fields of infancy

That his tears burned my cheeks, and his heart moved in mine.

These were the woods the river and the sea

Where a boy

In the listening

Summertime of the dead

Whispered the truth of his joy

To the trees and the stones and the fish in the tide.

And the mystery

Sang alive

Still in the water and singingbirds.

And there could I marvel my birthday

Away but the weather turned around. And the true

Joy of the long dead child sang burning

In the sun.

It was my thirtieth

Year to heaven stood there then in the summer noon

Though the town below lay leaved with October blood.

O may my heart's truth

Still be sung

On this high hill in a year's turning.

Dylan Thomas, Poem in October

The Goose Summers of the Autumn Saints

Probably the best known piece of weather folklore associated with a saint - apart from the one about it raining for 40 days if it rains on Saint Swithin’s feast day - is that of Saint Luke’s Little Summer. Certainly I was aware of it long before all the other bits and pieces I’ve picked up over the years.

Saint Luke’s feast day is 18 October, and the old saying goes that we always enjoy fine sunny weather for the few days before and after this date. Now, it may well be that this lore stuck in my mind early on because my mum’s birthday was 14 October and it nearly always turned out to be a glorious day. That was my own mythic marker of this point in the season and meant that I really did notice the weather from year to year.

Now comes the strange part. I first knew of Saint Luke’s Little Summer many years before I encountered the Julian calendar. As you may well know (and certainly will if you’ve been reading Bracken & Wrack for any length of time!) in 1752 the calendar was altered to take account of the slippage between calendrical and astronomical time. In the September of that year, eleven days were removed, giving us the Gregorian calendar that much of the world uses today. As time stands still for no-one, we are now thirteen days adrift of the Julian calendar, meaning that any seasonal or weather lore originating from before 1752 refers to conditions nearly two weeks later. And of course, the whole ‘feel’ of the season can have changed dramatically during that time.

This is odd, because I have certainly observed the reality of Saint Luke’s Little Summer. Even looking ahead at the BBC weather forecast for 18 October here in Norfolk I see it’s currently predicting sunshine all day. Not for the days around it, it has to be said: it’s a tiny summer this year :)

I wonder whether Saint Luke has garnered for himself TWO little summers? An old and a new? We shall have to gather again on All Hallows’ Eve (31 October, thirteen days later) to find out. But then again, according to folklore there can be several distinct spells of good weather in autumn. As well as Saint Luke’s Little Summer we have All Hallows’ Summer (now 13 November) and St Martin’s Summer around the saint’s feast day on 11 November (now 23 November). It’s really interesting to note how the old and new intersect at some points.

Spells of fine autumn weather used to be known as gossamer, a contraction of ‘goose summer’. The name refers to the time when geese were eaten, having been fattened up in the previous months and after grazing in the stubble fields.

These spells were notable for the visibility of gossamer threads, the mass of fine spider webs which catch the sun on a bright autumn morning. Now gossamer is used only to describe fine threads rather than ‘goose summer’ weather.

Other countries have similar traditions. In Greece, the Little Summer of St Demetrios is said to occur during the last two weeks of October, when sheep are led down from summer pastures to their winter grazing grounds. A final burst of fine weather before the saint’s feast day on the 26 October brightens the long and arduous walk. In Greek tradition, this is the event which marks the start of winter. But in compensation, St Demetrios’ Day is also when the first bottle of new wine is tasted ;)

Who was Saint Luke, anyway? He wasn’t one of the Twelve Apostles so is rarely painted on medieval rood screens in churches. But he is very often present somewhere in a church, often in the shape of his special symbol carved in stone or perhaps hiding, gilded, in a spandrel. The four evangelists whose names adorn the four gospels of the New Testament each have their own mythical beast ready to step in to represent them at a moment’s notice. Saint Mark’s is a winged lion, Saint Matthew’s a winged human (angel), Saint John’s an eagle (winged, obviously, and not really mythical to be honest) and Saint Luke’s a winged bull or ox.

Those ‘four living beings’ are mentioned in the Old Testament by the prophet Ezekiel as the bearers of the four-sided throne or chariot of God. Now, the number four is a very resonant one with many primal correspondences, so it’s not surprising that each of these mythical beings was associated with one of the gospel writers.

(Sorry for the digression, but where this gets really interesting is that these beings can also be linked to the four cardinal Zodiac signs - the lion for Leo, the angel/human for Aquarius, the eagle for Scorpio and the bull for Taurus …)

Saint Luke and his winged bull from The Book of Cerne, early ninth century.

Apparently, Saint Luke was allocated the bull because his gospel emphasises the sacrificial aspect of Jesus’ life and the bull was the archetypal sacrificial animal. Perhaps that’s pushing the metaphor a bit far. Still, it’s fascinating to realise that the saint’s feast day on 18 October is actually very close to the full moon known as the Hunter’s Moon or Blood Moon, when animals that could not be fed over the winter were killed and butchered.

But let’s not dwell on that. I think Saint Luke would prefer to share a recipe with us that uses the fruits of the season and packs a little bit of gingery heat too.

SAINT LUKE’S APPLE AND GINGER CRUMBLE

4 red eating apples - one each for the evangelists :)

1 thumb-sized piece of ginger, peeled and chopped

80ml apple juice

1 teasp cinnamon

2 tbsp dried apple pieces, roughly chopped

70g ground almonds

70g pumpkin seeds

75g coconut sugar

1 tbsp coconut oil

2 teasp ground cinnamon

1 teasp chia seeds

drizzle of maple syrup

Oven 180 C (fan setting)

Peel and core the apples, then slice into bite-size pieces. Place into a saucepan with the ginger and apple juice.

Bring to the boil, then simmer for 10-15 minutes until soft, adding water or more juice if it needs it.

While the apple cooks, place the dried apple, ground almonds, pumpkin seeds, coconut sugar, chia seeds, melted coconut oil, maple syrup and cinnamon into a bowl and give it a good mix.

When the apple is cooked, put it into a small baking dish and mash the pieces a bit with a fork. Sprinkle with cinnamon and drizzle with maple syrup before spreading the crumble mixture on top.

Bake for 15 - 20 minutes until as golden as a Little Summer’s day.

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

Today is St Luke’s feast day here and I’m going to cook the apple & ginger crumble. Although we aren’t having a little summer (we are having a wintery day in spring, so I guess that’s acceptable!)

Since reading this post, I’ve been remembering the prayer that I said when I was little

Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

Bless this bed that I lay on

Now I’m surrounded by all those mythical beasts!

Thankyou thankyou Thankyou!!!

I loved reading this, especially about St. Luke. It’s something that I can somehow weave into my own wobbly year.