Past the huts

the ring ditch

the broken tree

her path is strewn

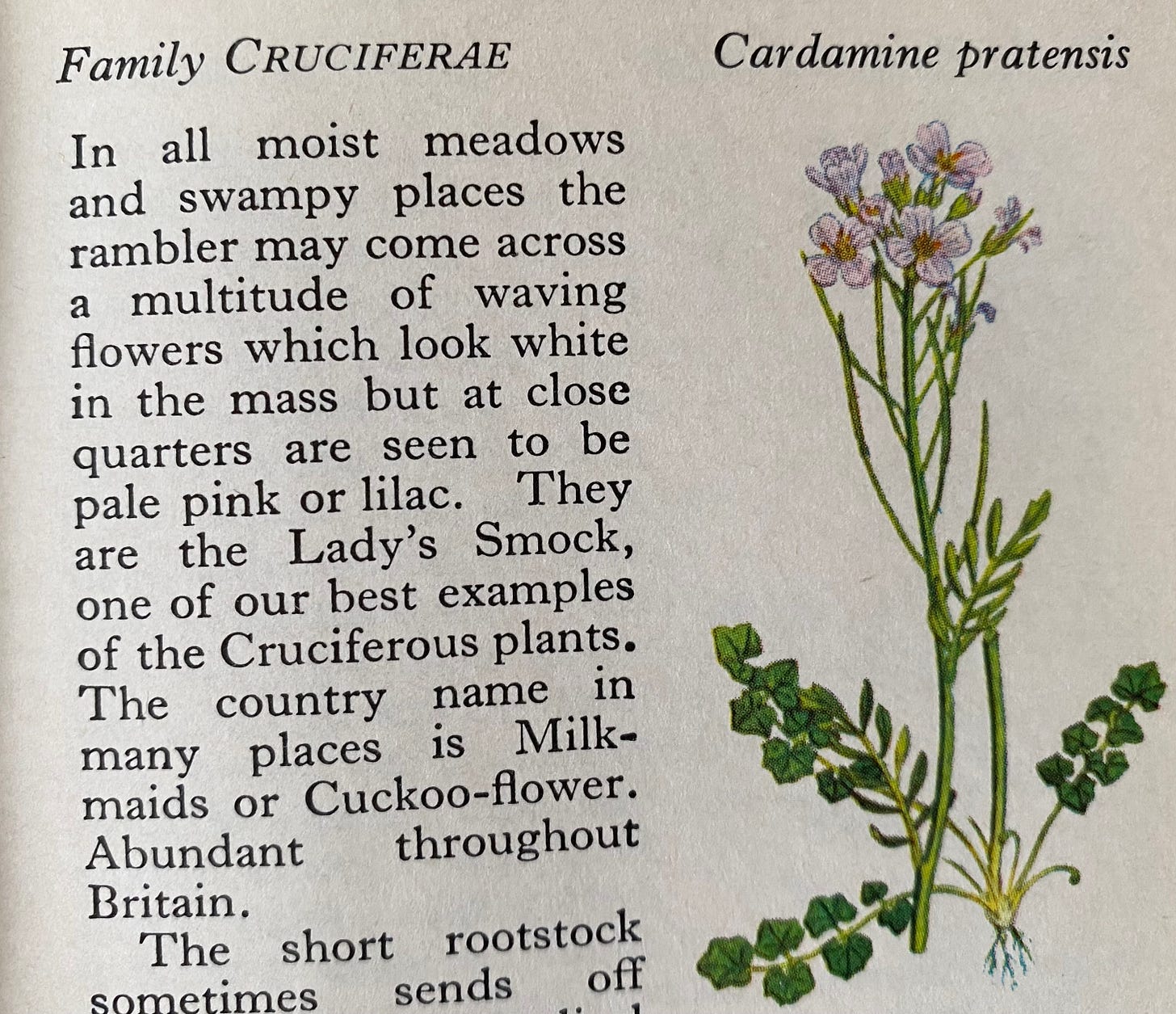

cuckoo-flower

chickweed

knotgrass

sloes

a woven dress

a trail

of heron feathers

in her hair

she rides

to the village

in the hunting boat

the girl who climbed

the broken tree

I offer with axes

I trade for peace

Victor Tapner, ‘Marsh Bride’, Flatlands

Marshes at Potter Heigham, Norfolk.

Hello and welcome to this full Snow Moon edition of Bracken & Wrack. Actually, there’s been no snow here in Norfolk this month (yet!) though we have had some frosty days so I may go with Catkin Moon instead, which was the name I plumped for last year. If you were reading this newsletter a year ago, can you remember what you chose for yours?

In this edge-of-spring issue we have:

Perseus: A Dazzling Stream of Stars

Croaks and Whistles (the not-so-secret life of toads)

Find Me In Your Own Face: Victor Tapner’s Flatlands

The Marsh Bride’s Flat-Cakes

On The Edge

Poetry by Ivor Gurney and Victor Tapner

PERSEUS: A DAZZLING STREAM OF STARS

Between the boughs the stars showed numberless

And the leaves were

As wonderful in blackness as those brightnesses

Hung in high air.

Ivor Gurney, ‘Between the Boughs’ (excerpt)

In Greek mythology, Perseus is the classical hero who is charged by King Polydectes with bringing back the head of Medusa the Gorgon, a monster whose gaze turns to stone all who look upon her. Perseus slays Medusa in her sleep, whereupon the winged horse Pegasus appears fully-formed from her body. Now riding Pegasus, Perseus continues to the realm of Cepheus, whose daughter Andromeda is about to be sacrificed to Cetus the sea monster in punishment for the vanity of her mother, Queen Cassiopeia. In the traditional telling of the myth, Andromeda waits, chained to a rock, for the sea monster to devour her and she is rescued just in time when Perseus kills it with his sword.

Now, according to Nigel G Pearson, some early depictions of the scene have Andromeda standing between two trees and also as actually holding the chain rather than being bound by it. This reading would, of course, put a different spin on things altogether and give a clue to another meaning of the myth. As the daughter of the great Queen Cassiopeia - whose story we will look at in a future full moon Bracken & Wrack - Andromeda is not beholden to any man and needs no rescuing. It is actually she who does the entrapping of the hero and initiates him into the mysteries of the feminine side of nature. As Pearson notes, the male powers are generally to be seen at the forefront of most activities but it is usually the feminine powers who are directing events behind the scenes ;-)

The story traditionally ends with Perseus using Medusa’s head to turn Polydectes and his followers into stone, whereupon he appoints Dictys as the Fisherman King. Perseus and Andromeda then marry, and have six children. All of this is remembered in the book of the skies, where Perseus lies close to the constellations representing Andromeda, Cepheus, Cassiopeia, Cetus and Pegasus.

Perseus appears within the river of the Milky Way as a brilliant constellation which can be recognised by its equilateral triangle marked by three bright stars, a fainter one glimmering at its heart. Issuing from this is a dazzling stream of stars. At this time of year, when I open my kitchen door and gaze at the stars before going to bed, Perseus lies straight above me in the western sky and a spectacular sight it is on a clear night.

I always look for Beta Persei or Algol (Demon or Ghoul). The ways of the ‘winking star’ seem to echo those of lunar magic which may be how the star acquired its Arabic name. Algol shines brightly for about two and a half days, the same period of time that the moon remains in each sign of the zodiac during a lunar month, after which it appears to go out. After glistening dimly for 15 minutes it regains its full lustre after nine hours, the number sacred to the moon. And as the Demon appears to be ebbing when it mysteriously retreats from the solar system and flowing as it re-establishes its lustre and travels back towards us, it even appears to behave like the moon-ruled tides of the sea.

Algol is Perseus’ second star. The first, Alpha Persei, is called Mirfak (Elbow), and like other beautiful old star-names it is always good to say out loud to fully taste of its syrup. As Claire Nahmad puts it - and doesn’t it tell you everything about the magic of stargazing - Mirfak is ‘festooned with stars gleaming like a precious bracelet around the elbow, their arrangement so pronounced in its symmetry that it seems possible that they are truly physically linked, veritable heavenly jewellery.’

Next time: Virgo

Webs on the heath, each covered in constellations of tiny droplets, 28 February 2021.

CROAKS AND WHISTLES

There is so much I could write about toads that it would be easy to fill a whole newsletter by exploring different aspects of their magic. And, as an occasional series, that might be a good idea. But here at the end of February we are slap bang in the middle of toad mating season, so let’s immerse ourselves in that truly amazing phenomenon this time around. Honestly, the more I discover about the workings of nature the more awed I am, and there was much about the journey between the twinkle in a toad’s eye and the hopping about of their offspring that was completely new to me.

So first let’s look at the starting point of the annual ritual: the mass migration of toads. As Lia Leendertz points out in The Almanac (2021), this migration may not seem epic compared to the round-the-world treks that some species make, but it’s happening right under our feet and is actually as perilous and fraught with danger as any other.

Throughout the earlier part of the month, toads will have been stirring from their hibernation where they have been tucked away in the mud at the bottom of ponds, under piles of leaves or deep in the ground.

Although they can live their whole lives on dry land, toads must have water to reproduce themselves. By the end of February they are on the move, the males setting out first towards the ponds where they were born. Their homing instincts are amazing and they travel several miles each night, making their way over every obstacle.

As toads walk rather than hop, crossing a road presents a great hazard and on known migration routes there are sometimes volunteer toad patrol groups who take turns to usher the line of toads across the road each night. I used to know where to turn into my parents’ driveway by looking out for the ‘toad crossing’ road sign that was almost opposite, indicating one such potent place for toad-kind. When you think about it, these routes resemble our own ancestral processional ways.

You have to hand it to those tricksy male toads. If one of them chances upon a female along the route, he jumps on her back and piggybacks a lift for the rest of the way. Once the home pond is reached, the couple will mate, or if a female arrives alone she will immediately be enveloped by lots of males all jumping on her to try their luck.

In the sexual embrace - known as amplexus - the male’s front legs are clasped around her to hold on, while his back legs are used to kick away any competitors :-) I have to tell you though that there is nothing romantic about this embrace, as his motive is simply to be the one closest to the female when she lays her eggs so he can immediately deposit his sperm to fertilise them.

Long double strings of eggs encased in jelly are laid right across the pond. The jelly disintegrates after 14 days, after which the tadpoles drop into the water (did you know that?!) to begin life in their own home pond.

This frenzy of breeding takes place late in February and lasts for 12 - 24 days. But there is a climax of 3 - 7 days when the males’ night chorus - described by Lia Leendertz as a sort of purring noise with croaks and whistles - reaches its height.

And the absolute pinnacle of that?

Often a full moon night, just like tonight.

‘Love Tunnel’ fishing jetty at Booton Clay Pit, Norfolk, heaving with spawn in the spring.

Long shines the thin light of the day to north-east,

The line of blue faint known and the leaping to white;

The meadows lighten, mists lessen, but light is increased,

The sun soon will appear, and dance, leaping with light.

Now milkers hear faint through dreams first cockerel crow,

Faint yet arousing thought, soon must the milk pails be flowing.

Gone out the level sheets of mists, and see, the west row

Of elms are black on the meadow edge. Day’s wind is blowing.

Ivor Gurney, ‘Early Spring Dawn’

First light from the bedroom window (video screenshot), 22 February 2024

FIND ME IN YOUR OWN FACE

‘These poems are laid out like a hoard of archaeological finds. They are glinting slivers of our ancient past in the East of England.’ - Tony Curtis

‘’Find me in your own time / find me in your own face’ says the centuries-old ‘Thames Idol’, and so say the others who people East Anglia’s prehistory in these spare, telling poems … These traders, lovers, refugees are part of us, and even the way the ‘Tidal Dwellers’ live at the mercy of the elements strikes an alarmingly contemporary note: ‘slowly / our houses / drown’. There is nothing distant about these people, nor the poems they inhabit: they are immediate, compelling, alive.’ - Sheenagh Pugh

You may have noticed that for several months now, I’ve been including Victor Tapner’s Flatlands poems in Bracken & Wrack. This slim volume has been on my shelf for several years, and although Tapner was born in Watford, grew up in Bedfordshire and now works as a writer in Essex, as a Norfolk girl his poems speak strongly to me.

What Victor Tapner has done with Flatlands is to place himself in a stripped-back East Anglian landscape during tribal times. Often it’s uncertain whether any given poem is set in the Neolithic or even back in the Mesolithic, or in the Bronze or Iron Ages. In truth, the needs, desires and preoccupations of people in many ways changed little during these millennia and have, in essence, changed little still. The poems that are set during Roman rule are more clearly of their period, but even so we recognise the same human emotions and reactions as those of earlier times. And as ours, too: we who tread the land in the here and now.

Always stark and spare, every word has to earn its place and for me as someone who adores both reading and writing, this is thrilling. We learn all we need to know from ‘our lame boats / trod the sleet sea’, or ‘let the trees carry / your hunting cries’, or ‘We sip from cups / rich with lime / and meadowsweet’.

These poems are visceral and place you right there among the chalk-torn faces, blood-flecked hands, rotted corn and dripping meat hooks. But we also glimpse fleeting moments of tenderness: ‘You rubbed a leaf / of willow-herb / I breathed your hand’ or, in ‘Shale Bracelet’, ‘Her band of darkest blue / glinting / like an eye glints / skin smooth / wrist round / thin / as her thinnest bone’.

Mostly though, there is a raw earthiness, a matter-of-factness that can’t be prettied up or shied away from. On a first reading of many, probably most, of the poems, I’ve thought, oh I can’t include that, the first stanzas were so beautiful but suddenly we’ve come to uncomfortable or graphic or jarring imagery that hits a nerve and will probably upset people. Or perhaps I come to a line I want to skip past like ‘we tell how we bled / the hungry wolf’ when from my contemporary perspective I think of the wolf as a powerful, magical creature, strong of heart and fleet of foot and don’t want to think of a hair of his head being harmed.

But as the months have gone on and I’ve often turned to Flatlands for a seasonally appropriate poem, I’ve come to feel that this very discomfort is where the treasure lies. By unflinchingly evoking the sounds, sights, tastes, smells and textures of the prehistoric world, Tapner gently but insistently forces us to meet the sublime face to face. By which, I mean that exquisite blend of the beautiful and the terrible that reflect back and forth between the natural world and our own human experience.

I find myself wanting, for example, the love poems (or what I take to be love poems) to be wild and exquisite. And they are, if you take the dictionary meaning of exquisite as ‘intensely felt pleasure or pain’ or ‘extreme in degree, power or effect’ But even these are not pretty. There’s no time to linger on the almost-tenderness at the start of Bees’ Nest: ‘Breakfast milk / still on her breath / I taste / her oaten tongue’ before we are thrust forward to the end where: ‘we bite like goats / snarl like dogs / plead like sheep / tethered for killing’. But that’s the way it is, and for me anyway, all the more powerfully affecting for its rawness.

With bare-bones poetry where every word hangs like wild honey, I sometimes find myself wondering whether the images I respond to would have the same effect on every reader, as I tend to naively imagine. Maybe some would, as certain motifs have resonance to us all in our common humanity. But over and above this there must be experiences and memories individual to each of us that lead us to be drawn to some pieces more vividly than to others.

For me Marsh Bride, the poem I chose to include the top of this newsletter, is like that. Does this title speak to you as it does to me, I wonder? It’s not that I can explain or articulate exactly what it is that pulls my heart. Partly, maybe, it’s because my maternal ancestry comes from deep within the East Anglian fens and also because I am drawn to the Anglo-Saxon anchorite Saint Pega who chose to travel deeper into the marshy fen rather than returning to her former life in a noble Mercian household.

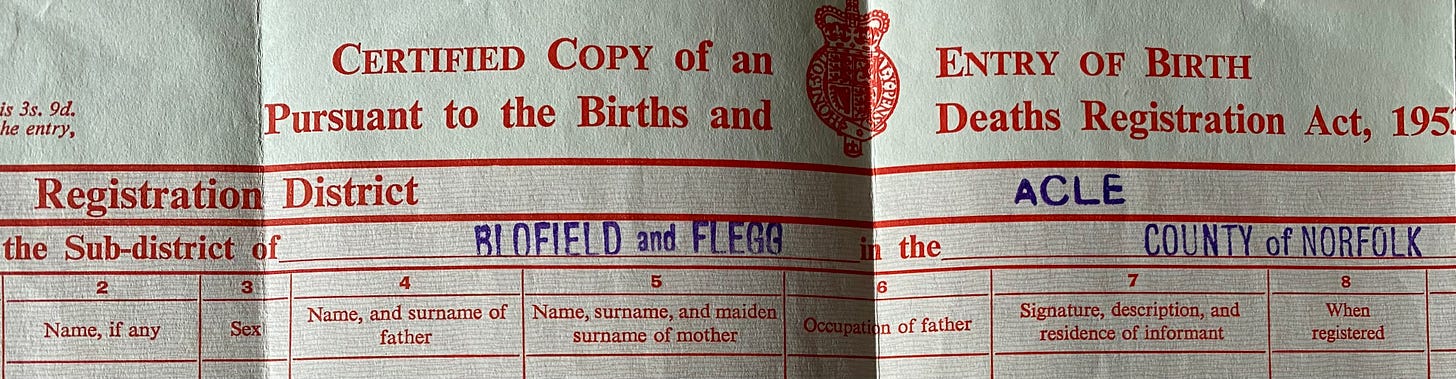

Then again, I’ve always been inexplicably proud of the fact that my birth registration district within Norfolk is Blofield and Flegg, a sub-district of Acle. Admittedly this happened through a strange quirk of county division as I was actually born in an eastern suburb of Norwich, but if you know Norfolk you will realise that the named places lie in one of the most watery, marshy areas of the county. Deep within the Broads, it’s an area still revealing its ancient secrets.

And it is very marshy. Indeed, the name Flegg comes from flaeg, an old Danish word used for all sorts of marsh plants. Properly called the ‘Isle of Flegg’, in times past the only way to approach this slightly higher ground from any direction was over water. The translation of its name as ‘the place where reeds grow’ is perfect as its extensive marshes and waterlogged peat soil are still very much in evidence. I must confess that I even feel a little surge of excitement when I see a signpost like this one that points only to the marshes.

And there’s the list of plant names: ‘cuckoo-flower / chickweed / knotgrass / sloes.’ I am endlessly enchanted by knowing that I can touch, smell, sometimes even taste or make dye or medicine from a wild plant, and that the same sensations will have been experienced in exactly the same way by my ancestors hundreds and maybe thousands of years ago. Wild plants make us all time travellers, or perhaps more properly can be said to exist outside of time.

The feel of a rough-woven dress. A trail of heron feathers. A girl who climbs trees. The weight of a stone axe in the hand.

Tell me about the words that conjure memories for you and bring you alive. A sentence from a book or film, a few words of poetry.

I would love that.

THE MARSH BRIDE’S FLAT-CAKES

For this recipe (based on a Deliciously Ella one) I have taken inspiration both from the Marsh Bride herself, who would need some simple cakes in her repertoire, and also from the lover in Bees’ Nest with ‘breakfast milk/still on her breath/I taste/her oaten tongue/spittle/sharp with berries’.

I imagined these as simple cakes made from a berry-studded batter dropped onto a flat stone heated at the edge of a fire. Of course the ingredients are not entirely correct and we will be using a frying pan so for us they’re pan-cakes but, well, half close your eyes and look over there. Can you see an earthenware vessel filled with a mixture of coarsely ground grain, sheeps’ milk, butter, a handful of poppy seeds, wild honey and berries?

300g self-raising flour (or use spelt, or gf - if you choose not to use self-raising flour the cakes will be flatter and more prehistoric looking)

50g porridge oats, ground or processed finely (or use oatmeal)

400ml plant based milk

a handful of berries (ideally wild berries such as wild raspberries, bilberries or cranberries or failing that use blueberries)

1 tablespoon maple syrup (or honey for authenticity if you’re not vegan)

2 tablespoons coconut oil, melted, plus extra for cooking

1 teaspoon chia seeds

pinch of sea salt

Stir all ingredients together except the berries, until a thick, smooth batter is formed. Once mixed, add the berries and mix again. Leave for 5 - 10 minutes to thicken.

Warm a little coconut oil in a pan over medium heat (if you use this pan to melt the coconut oil for the recipe you can begin by using the residue).

Once the pan is hot, spoon in a large tablespoon of batter, using a wooden spoon to spread out the mix.

Cook on one side for 3 - 4 minutes until golden before turning over and cooking the other side for 2 - 3 minutes until cooked through.

The alder carr, 24 February 2024.

ON THE EDGE

The renowned academic Oliver Rackham, whose specialist area was the history and ecology of trees and woodland, once said that if you seek the most ancient trees in the landscape don’t go looking for them in woodland. Yew trees can live for thousands of years, but the oldest are generally to be found in churchyards. Apart from the yew, our longest-lived native tree is the oak. And the most venerable oaks usually survive as remnants of ancient boundaries.

Often, the original boundary whether of enclosure, field or copse may not now exist, but one or two of the oaks that once formed an imposing row will still stand within a hedgerow or between two fields. Ordnance Survey maps even mark some lone trees and you will see the word ‘oak’ here and there in archaic writing, signifying age and, by implication, layers of story.

Occasionally the age of an individual tree is known with some accuracy. There is a boundary oak within Sheringham Park in Norfolk that is said to date from 1348, around the time of the Black Death. Norfolk’s most famous oak, Kett’s Oak still stands on the road between Wymondham and Hethersett, and was surely a boundary marker too. This is the place where, in 1549, Robert and William Kett assembled and addressed a group of hugely motivated angry and desperate men in what was to become Kett’s Rebellion. Later, nine of the men were actually hanged at Kett’s Oak.

Where the boundary has been more recently planted and the trees are younger - though visibly older than the other trees they stand sentinel over - you may still find a full row of oaks marking the edge of a wood. It’s then that you begin to get a feel for their true role. Yes, they guard the edges and stand firm while trees like the birches with far shorter lifespans come and go, safely held within their bounds. But the oaks do far more than this.

For one thing edges are, well, edgy. Liminal places, which the steadiness of the oak does much to stabilise in a psychic sense. The inside and the outside of any given space are clearly delineated by the massive trunks, their branches stretching protectively towards each other to touch fingertips, keeping the energies where they need to be. This can certainly be sensed when you walk a path beside an oaken boundary, as I do whenever I visit Acorn Wood.

Self portrait at the boundary oak, Acorn Wood.

Like humans, no two oaks are ever alike, and you get to know each one for its own personality and aura. In Earth Magic: a wise woman’s guide to herbal, astrological and other folk remedies, the eponymous Victorian Yorkshire wise woman speaks of a spell to commune with the spirit of a tree, and while you may be guided to befriend any tree that your heart selects as its own, I would say that a boundary oak would be a very safe choice.

In the book, the wise woman suggests finding a tree that you sense welcomes you. Give your tree a name that honours it, she says, and keep that name secret. You will be the tree’s spiritual friend, and it will be your magical companion. A bond of love and knowledge will begin to grow between you. Place your hands on the bark and embrace the tree, saying:

Tree-spirit, hear my prayer

True friendship with you I would share.

If all feels harmonious, a further charm is said to bind heart to heart and soul to soul, and a lock of your hair tied around a twig and buried among the roots. ‘Visit your tree often and enter a deep communion with it, but do not think this can only happen when you stand beside its greenery in the summer and its good bare bones in the winter. Think of your tree many, many times as you live your life day by day; tell it of your joys and sorrows and the secret longings of your heart. In happiness, rejoice with your tree; in pain, put your arms around its strong trunk and it will take the pain from you. In times of mental distress or unease, make a picture of your tree in your mind’s eye; see its stillness and its gentle exhalation of peace, and breathe with your tree.’

This, or something akin to it, would be a lovely, reciprocal practice to try.

Boundary oak, Acorn Wood, 23 February 2024.

You may feel that all this is a bit airy-fairy as I haven’t yet mentioned the incredible life of the oak in an ecological sense. After all, no tree supports more other forms of life than the oak. And then there is all the folklore surrounding oak trees, but to do justice to that would require not just a whole newsletter but a whole book. And speaking of books, there are plenty of good books out there that cover everything you ever wanted to ask about oak trees and plenty more besides. One example is The Glorious Life of the Oak by John Lewis-Stempel, another is The Oak Papers by James Canton, and there are many more.

But back to the oak as boundary keeper. The Acorn Wood oaks, although pretty old, are equally not among the most ancient of their kind that I’ve encountered. Sometimes the presence of the oldest ones is now marked only by a row of massive stumps along the line of a landscape feature like a footpath, holloway or field division. These may themselves be almost obscured by vegetation so that you suddenly come upon one of them and are led to the next, and from there you feel the need to see how far the line stretches, marvelling at the age the trees must have reached at the time of their felling. This is exactly what happened beside an ancient trackway close to my old home in Reepham in Norfolk.

This footpath or greenway followed an old orientation, focussed on a long-demolished manor house and running beside the last remnants of the village’s medieval strip field system. On either side of the path, the hedgerow had become in effect a linear woodland, forming a glorious green tunnel. In summer the waving leaves and shifting light and shadow made it feel a little like being underwater.

It was a favourite place in itself, but even more so when I walked into the field that bordered one side of it to discover massive oak stumps that helped to prove beyond doubt that this was a true ancient Way. At the time I was making a series of art interventions along the track to try to draw attention to the likelihood of its imminent destruction, unlucky as it was to lie in the way of developers. Fortunately it was saved at that time, as were the stumps which would also have been unceremoniously torn out. When magnificent beings have stood in place for hundreds of years, surely what remains to mark their lives (and to reveal the history of the landscape) should be honoured and respected.

So huge were the stumps, that I was able to use one of them as the background to arrange 30 quite large gingerbread people on it for a photoshoot to document one of the artworks. Under Your Feet was made from gingerbread people, each of whom carried a currant letter on its front, so that together they created the W B Yeats line: I have spread my dreams under your feet. Then they were separated, hung up in the trees along the footpath and left to their fate. It’s just occurred to me how much this fits in with what I was saying about the men who were hanged at Kett’s Oak, as this was one of the references I had in mind.

You can hardly see the boundary oak stump, but all these gingerbread people fitted on top of it. Location shot from ‘Under Your Feet’, Reepham, Norfolk.

I have the feeling that the Acorn Wood boundary oaks will be left to their fate, too. At least two of them were toppled in fierce September storms more three years ago, and they’ve been left where they lie, gradually playing host to more and more other forms of wildlife as they rot.

One of the boundary oaks that toppled in the storms. Now the path goes right beneath it which is wonderful.

It would be sad if one of these happened to be your chosen soul-tree, but I imagine it taking a great deal longer than the rest of our current lifetimes for these giants to disappear completely. Until then, they need friends. And so do we.

We need the oaks as much as they need us.

Hare, haw and boundary oak.

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

Thank you, Imogen, for another beautiful delivery of words. I shall be ordering Flatlands immediately. I’ve not heard of Victor Tapner before but I think his poetry will speak to me profoundly (I live on the Suffolk-Essex border). You asked for words that had a particularly deep effect on people and a line that always leaps to my mind is ‘a petrel flew in the rain’. The words come from The Ice Shirt, by William T Vollman, a novel that imagines the incursion of Norse people into what came to be called North America, in the 10th century. It’s full of weather and ice and storms and harshness, and this line so completely encapsulates the mood of it: you can feel the driving rain and the cold and see the grey sky and you know how indifferent the weather is to the fragile humans below.

Thank you for your words and inspiration!

Thank you Imogen, for such a lovely collection. I love ‘Marsh Bride’, and the ‘trail of heron feathers’. Heron is my special friend - he has appeared to me many times and brought me comfort during sadness and has encouraged me to be still, until the worst is over. Amazing information about toads! I must learn more! Thanks also for introducing me to Victor Tapner’s poetry - for seasonal appropriateness and ‘discomfort’, it puts me in mind of Ted Huges’ November - “month of the drowned dog”. I find this poem jarring and depressing, and yet I revisit it often in the winter. If I want to feel better, I read Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese. Have a wonderful day, and enjoy your magical garden x