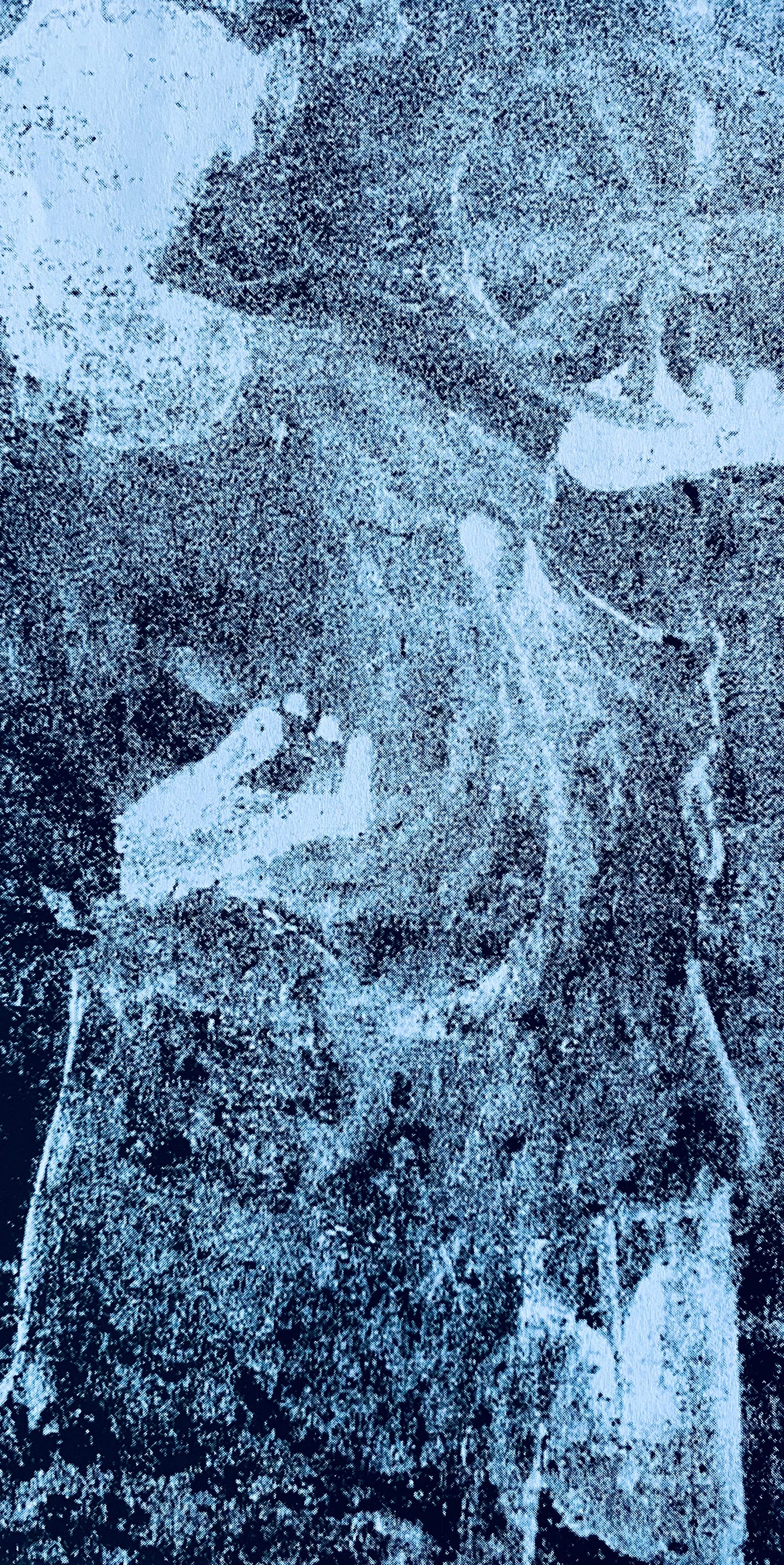

Wild Woman on the font, facing the main (south) doorway of St Catherine’s church, Ludham, Norfolk, 25 November 2024

Hello, lovely Between the Moons friends!

And today, that’s EVERYONE as I’ve decided to send this Substack post out to all Bracken & Wrack subscribers. It’s another celebration of our publication’s two-year anniversary which fell on 23 November. That’s Old Clem’s Day (St Clement’s Day) which is also Wayland the Smith’s Day. All in all - and I have to admit it’s by coincidence - rather a resonant date.

First, though, a little bit of housekeeping. If you enjoy this article and are able, please do consider supporting this publication with a paid subscription. You may be thinking, this is all very well Imogen, and I know you studied art full time for five years and have written all your life and feel that surely you should be able to make a very modest living from these things, but there’s no way I have time to read ANOTHER 3.5k word article twice a month.

Please rest assured that although this post has stretched into quite an essay, actually my ‘between the moons’ offerings are meant as a simple thank you to those who are able to help me spend so many hours researching and writing, and that going forward I intend to employ a bigger variety of media for this purpose. Substack keeps introducing new features, and now makes it easy to upload a video or podcast which those short of time may find more palatable. Other suggestions are welcome! Meanwhile, of course, my Bracken & Wrack newsletters sent every new and full moon will always be free to all.

And now, let’s get started.

Shrines & names

During visits to some of the Greek islands many years ago, I was always touched to come across one of the many wayside shrines to lost friends or relatives, often set up next to an especially treacherous-looking bend in a road. These shrines are like tiny pitched-roofed houses on legs, and within their glass walls they usually contain a photograph of the deceased, a bottle or can of their drink of choice, sometimes an item of clothing or other favourite possession - and an icon of their namesake saint with the flame of a little oil lamp constantly flickering before it. Very few babies, it seems, are not named after a saint who will watch over them in death as well as in life. And these shrines are also carefully and lovingly tended by those left behind. Attached to one of the legs you’ll always see a cloth for shining up the glass and a bottle of oil to keep the lamp alight.

When I was at school, most of the boys in my class shared their names (if nothing else!) with saints. Andrew, Mark, Stephen, Michael, Peter, Matthew, Simon, John, Martin, Paul, Philip - all these names were very common. Perhaps there were fewer girls’ names that echoed those of female saints, but still there were some Marys, Annes, Margarets - and Catherines.

One name that definitely had no saint ‘double’ who might perhaps act as a touchstone and guardian for its owner was, of course, Imogen. But even my very earliest memories involve a saint whose name I learned to recite probably by the age of two or three and my hand was taught to write in enormous childish letters at not much older than that. Knowing my mum it was probably a safety device in case I got lost. But still, I clearly remember repeating in a sing-song mantra -

Imogen Ruth Yates 34 St Catherine’s Road Thorpe St Andrew Norwich NORFOLK!

Yes, two saints names in one address :-) Perhaps it’s no wonder that I have a liking for those scratched and faded wild saints in their painted medieval panels. And it could be said that I have even more justification in thinking of Catherine as ‘my’ saint having come into the world on a road named after her. Most babies were born at home at that time, and I was no exception.

Catherine’s story

According to her legend, Catherine of Alexandria (who happens to have been Greek) was martyred for her faith when she was 18 years old. From a young age she devoted herself to study, before a vision of the Virgin Mary and child persuaded her to convert to Christianity at around the age of 14. When the persecution of Christians began under the emperor Maxentius, she went to the emperor and rebuked him for his cruelty. The emperor summoned 50 of the best pagan philosophers and orators to dispute with her, hoping that they would be able to turn over her arguments, but Catherine easily won the debate. Several of these philosophers were so convinced by her eloquence that they, too, became Christians and were immediately put to death.

The emperor gave orders to subject Catherine to terrible tortures and then throw her in prison, during which time she was fed daily by a dove from heaven. Jesus also visited her, encouraging her to fight bravely, and promising her the crown of everlasting glory, while angels tended her wounds with salve.

During her imprisonment more than 200 people visited Catherine, including Maxentius' wife, Valeria Maximilla, who was promptly put to death by her delightful husband. Everyone who spoke with her was convinced to become Christian, and was subsequently martyred. When Maxentius realised that torture would never make Catherine renounce her faith, he tried to force her into marriage as a bribe to win her freedom. Of course, Catherine refused, asserting that her husband was Jesus to whom she had pledged her virginity.

On hearing this, the now apoplectic emperor condemned Catherine to death on a spiked breaking wheel, but at her touch it shattered. Exasperated, Maxentius ordered her to be beheaded. Catherine faced her fate without demur and the deed was done, but it was milk instead of blood that flowed from her neck.

Catherine holds a special place in the constellation of saints, being one of the 14 ‘holy helpers’ and, it’s said, a major inspiration to Joan of Arc who received succour and encouragement from her. Was she a historical person or is her virgin saint story (like so many others) a version of the same legend in which a young girl refuses to yield to a pagan suitor and give up her faith, paying the ultimate price for her conviction? Perhaps it does not really matter.

In The Stripping of the Altars, Eamon Duffy explores the cult of the virgin martyrs. He lists whole groups of them - nearly all with similar grisly and sensationalist stories - who feature on East Anglia’s medieval rood screens and so give us a glimpse of the awe in which they were held. The most frequently portrayed are Catherine, Margaret (who cut her way out of a dragon) and Barbara (who was tortured and beheaded when she refused to marry a pagan and give up her prized virginity). But by the late medieval period these three were joined by a whole galaxy of more or less identical virgin saints. In North Elmham in Norfolk, eight of them occupy the entire south side of the screen: Barbara, Cecilia, Dorothy, Sitha, Juliana, Petronella, Agnes and Christina. At Westhall in Suffolk there are also a group of eight: Etheldreda, Sitha, Agnes, Bridget, Catherine, Dorothy, Margaret and Apollonia.

St Apollonia holding aloft a tooth in giant pincers. One of the ‘virgin saints’, her torture included having all her teeth pulled out. Naturally she was invoked by those with toothache. St Catherine’s church, Ludham, 25 November 2024

With their theme of the preservation of sexual purity, it might be thought that these groupings were intended as exemplars for the congregation to live up to. But as Duffy goes on to explain, the dynamic of such imagery - and of prayers directed to such renowned virgins as Mary and John the Evangelist - was not designed to present the chastity of the saint as a model to imitate. Rather, this same chastity formed the basis for their intercessory power, rather like a super-charged battery pack. Virginity was a symbol of sacred might, and what it gave to the parishioner was not so much an ideal to aspire to - something most ordinary people would never have dreamed of - but a magical current to be tapped into.

Talking of magic, as a child there was little more magic imaginable to me than the enchantment of bonfire night on 5 November. At St Catherine’s Road - and later in Old Costessey where we moved when I was seven - we would always have a small box of fireworks and a packet of sparklers that evening, accompanied by my mum’s homemade bonfire toffee and followed by Heinz tomato soup and jacket potatoes. It was always my dad’s job, and absolutely definitely no-one else’s, to 'light the blue touch paper and retire’.

The stumpy, colourful little packages smelling excitingly of gunpowder had names like Chrysanthemum or Silver Fountain or Roman Candle. And f course, there was always a Catherine Wheel, tightly coiled and begging to be nailed to a fence post and to have the taper touched to it. Even when I was tiny I always knew that there would be just one shot at the spectacle, and that there was only a moderate chance that it would actually light properly and spin freely, showering its array of golden sparks into the November dark. So I held my breath. But oh, the thrill when it did.

You might not know anything about St Catherine, but you will almost certainly have heard of her Wheel. I think that even as a child I had an inkling that it held an exquisite double-edged beauty much like the sword that martyred the earnest young scholar.

A constellation of candles in the Orthodox Chapel at Walsingham, Norfolk. The coming of St Catherine’s Day signalled to Nottinghamshire lace makers that it was time to light their candles so that they could see to work indoors

Perhaps not surprisingly since the wealth of medieval Norfolk rested on wool and its attendant arts of dyeing, spinning and weaving, Catherine has traditionally been held especially dear as a patron and advocate here. On faded rood screen panel and crumbling wall painting alike - or even as a fragment in a patchwork of ancient window glass - she is readily identifiable by the wheel she holds aloft. And of course, that forged an immediate connection to the benign wooden version whirring daily in many a household.

Val Thomas speaks of the local connection in her magical lockdown diary, Bounded In A Nutshell. In her entry for St Catherine’s Day (25 November) she says:

St Catherine’s Day has always been a special one for me, as a spinner. But I was a little wistful today, thinking that normally I would be getting out all the spare teaching spinning wheels, drop spindles, carders, baskets of fleece and plant fibres, ready for anyone who wanted to come and join me in ‘keeping up the day’. As St Catherine is the patron saint of lace makers, as well as spinners, ‘cattern cakes’ are particularly popular in Nottinghamshire, an important centre for their craft.

Val goes on to give a cattern cake recipe, similar to a version I have made before, which was very nice. The essential flavourings are cinnamon and caraway. I shall use Val’s recipe as a basis here, giving it a few tweaks of my own to turn it into a vegan offering. As we shall later see, Catterntide is really a stretch of time rather than a single saint’s feast day, so these cakes are very suitable for any time around now, and delicious with a cup of tea or coffee - or mulled wine maybe.

Cattern Cakes

225g self-raising flour

1 tsp cinnamon

60g currants

60g ground almonds

2 tsp caraway seeds

150g caster sugar (I use coconut sugar)

100ml olive oil

2 tbsp chia seeds soaked in 2 tbsp water for 10 mins

(to replace an egg) plus a splash of plant-based milk

Extra sugar and cinnamon for sprinkling

Mix dry ingredients. Add the oil and chia ‘egg’, adding a splash of plant-based milk if necessary as the chia will be less liquid than an egg. Don’t make it too wet though, as it needs to be a stiff dough.

Roll out on a floured surface to around 12” x 10”. Brush with water and scatter with extra sugar and cinnamon to taste.

Roll the dough up loosely and cut with a sharp knife into 2cm or three-quarters of an inch slices.

Space apart on a lined baking tray.

Bake in a pre-heated oven at 200C, 400F, Gas 6 for 10 - 15 minutes, then cool on a rack, sprinkling with extra sugar and caraway seeds if you like.

Black Catherine?

‘Map’ - A0 poster - the three virgin saints Margaret, Catherine and Mary Magdalene are pinned outside the north doorway of Hackford church, Norfolk.

As Catherine is so well-loved, it’s quite natural that she would feature in the ancient group of three female saints - Mary Magdalene, Catherine and Margaret - painted onto the wavering walls of All Saint’s church, Little Wenham near Ipswich in Suffolk.

The images are huge and haunting, at least life size, and what makes you catch your breath on first sight is that although their features are now completely invisible, the skin of their faces and hands is pure black. Was this deliberate, in the way that tradition has grown up around the image of the Black Madonna? There is actually a separate Madonna and child wall painting in another part of the church, and both mother and child also have black skin. Logic says that in the mundane world it’s a quirk of oxidisation affecting a specific medieval pigment, but the impact of the paintings on the viewer takes no account of this. I loved them when I visited and could not take my eyes away.

The three saints stayed with me, and I made a whole series of work inspired by their presence. I’ll tell you more about that another time, but for now I wanted to give you a glimpse of a couple of the ways I kept them close. Of course you will know Catherine by the Wheel resting lightly in her opened hand.

St Catherine with her wheel - reverse/negative image, photocopy (from the wall painting in Little Wenham church, Suffolk.

A sudden fancy

A couple of days ago, on the afternoon of St Catherine’s Day, I had a sudden fancy to go to visit a medieval church dedicated to the saint whose name I’ve heard practically from birth. I decided to go to Ludham, which isn’t far from here. I couldn’t remember whether Catherine’s image is set into its fabric anywhere, but in any case I thought it would feel like a bit of a pilgrimage on her special day. I was also familiar with one extraordinary feature of that church, and felt it was high time to visit to pay my respects again.

Stepping into the high, light interior of the church I went straight down to the rood screen, wondering if I would find Catherine’s likeness painted there in a 15th century hand. Two beautiful images of female saints book-end all the male ones - Mary Magdalene with her jar of precious ointment and Appollonia, friend of those with toothache, holding aloft a huge tooth in a giant pair of pincers. Grotesque and characterful stone faces stare at you in whichever direction you face, and carved angels look down from the hammer beams. But Catherine’s image is nowhere to be seen.

I began to wonder whether the church was actually a later dedication and had perhaps first been named for someone else. But picking up the guidebook later, I discovered that had I looked more thoroughly I would have spotted Catherine’s wheel carved into some of the pierced wooden spandrels holding up the roof beams.

Having wandered around, soaking in the late November sunset through the tall, many-faceted windows and photographing some of those staring faces leaping out of the stonework, I made my way back towards the doorway. There, in full view of the main doorway, stands a most unusual stone font. In fact, it’s unique, and the thing that makes it so is actually the carving right in front of you as you step in.

Ludham is probably most famous for the folklore surrounding its dragon - the Ludham Wyrm - but I wonder how many people have seen its Wild Woman, the only known carved depiction of a female woodwose? Her counterpart, the male wild man or woodwose, stands behind the font facing the north doorway, and he is quite a common motif in church carving in general, but it is she who takes centre stage, and she is unequivocally female.

Our Wild Woman has long hair, a body completely covered in hair or fur, and like the male woodwose carries a large club in one hand. Unlike him, however - and this is not something I have seen mentioned anywhere but couldn’t help noticing - her other hand is doing something quite different. Look closely and you will see that, like a sheela-na-gig, her vulva is exposed and enlarged and then see where her hand is. No wonder the church guidebook fails to point this out ;-)

So, you may be wondering, whatever does all this have to do with our graceful and learned young maiden, wedded to Christ and with quicksilver thinking that would win any debate? It’s a good question. But with no statue of Catherine in her church, the wild woman makes an interesting image to ponder.

Traditions around the Feast of St Catherine have been beautifully researched and written about by such favourite Substackers as Jacqueline Durban in Radical Honey and Caitlin Matthews in A Hallowquest Sanctuary among many others, and I thoroughly recommend diving down all the rabbit holes out there.

I am entranced by all of this, but first and foremost for myself I always come back to this being a Tide rather than a single day that comes and goes, or even two days if you celebrate 25 November as ‘new’ St Catherine’s Day and 8 December, 13 days later as the ‘old’ one, showing us how the world would have felt to our ancestors who lived before the calendar changed in 1752.

So, here is the way my wandering mind has been turning. We are now in Catterntide, which in many cultures has been seen as the women’s gateway into winter. The men’s gateway into winter traditionally falls at Martinmas on 11 November, but if you make the same calculation and project forward 13 days, you come to 24 November which is, of course, St Catherine’s Eve. Can you see how already the Tides are weaving together?

But there’s more. Old St Catherine’s Day, as I said, falls on 8 December, and that date was once the midwinter solstice, as it’s exactly 13 days from then until 21 December.

Now this may look like a bit of mix-and-match between the Julian and Gregorian calendars to suit my purposes, and of course it is. But still, I find these threads fascinating, and they certainly show us how the Tides flow and mingle and overlap, very much like the baby wavelets I love to watch on the shoreline at my closest beach.

Wavelets at Walcott, 26 November 2024

The furious host

But what of our Wild Woman? Can she possibly have relevance to this line of thought?

Well, I did mention the link between Old St Catherine’s Day and the winter solstice.

And this Tide or gateway to winter, by many accounts, is exactly the time when the Wild Hunt begins its nocturnal coursings. According to Nigel Jackson in Masks of Misrule, this is a time when the world order is mystically reversed and annulled to form portal-gateways through which the Wild Hunt rides forth ‘when old time has dissolved but new time is yet to begin’. In some traditions this wild and anarchic Ride, sweeping up lost souls, takes place during the Twelve Days of Christmas, while in others it begins with the winter storms at Samhain or All Hallows’.

There are so many variations on the details of this Wild Hunt (Wutanes Heer in Germanic languages = Furious Host) but in several of them, the Wild Huntsman is accompanied by the Wild Huntress. In Germany, the Lord of the Host was ‘the magician-sovereign and ecstatic death-god Wodan, and by his side rode the Wild Huntress variously known as Frau Wode, Frau Frie, Frau Perchta or Holda’. The Host were known to travel through the skies by night, accompanied by shouting voices and ringing vibrations.

In Shropshire tradition the image of a Horned Master merged with the 11th century figure of Wild Edric, a historical hero who resisted the Norman conquest, leading an uprising from the Welsh borders into Herefordshire and sacking the town of Shrewsbury in the year 1069.

Wild Edric and his faery wife, the Lady Godda, have been witnessed leading a wild hunting band, as Nigel Jackson relates in this first-hand account recorded in Shropshire Folk-lore by C S Burne and G F Jackson (1883):

‘… she heard the blast of a horn. Her father bade her cover her face, all but her eyes, and on no account speak, lest she should go mad. Then they all came by: Wild Edric himself on a white horse at the head of the band, and the lady Godda his wife riding at full speed over the hills.’

Perhaps on a wild and stormy night you will sense the passing overhead of that chaotic band of riders - but do make sure not to look at them, won’t you? And just maybe, the Wild Woman of Ludham is in exactly the right place, at the right time.

After all, this is Catterntide, and it’s never the wrong moment to stop for a moment, to pause and really feel where we are on the turning Wheel.

Even if it’s not the one special wheel that, each November, Catherine herself steps down to renew for us, so that it can be nailed again onto that fencepost of childhood memory full of wonder and anticipation.

There, it’s free to spin and spin and spin in the dark, releasing wild sparks in every direction, the after-flare of its stars staying deep within our eyes.

Exploding sparks: Catherine Wheels in the lane, 27 November 2024

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

That was fascinating to read! I've written about the wild hunt before but now I'd like to write about the wild woman...

It’s wild to note how much we are still persecuting strong minded women!

I do like the Tides and I am still planning on making Cattern cakes- something I look forward to every year!