Sweet month thy pleasures bids thee be

The fairest child of spring

And every hour that comes with thee

Comes some new joy to bring

The trees still deepen in their bloom

Grass greens the meadow lands

And flowers with every morning come

As dropt by fairey hands.

John Clare, from April in The Shepherd’s Calendar

Soon, there will be apple blossom! The garden at The Old Shop, 6 April 2023.

Full Moon: Pink Moon

This full moon is properly the Paschal Moon as it’s the first one after the spring equinox. This means that it determines the date of Easter Day, which is always the following Sunday. I like this blending of natural rhythms, celestial phenomena and the spiritual.

But this moon has many other names too, and the one you will most often see quoted is the Pink Moon. I’ve often wondered whether this means that the time of year influences its colour. A little research reveals that the name, like so many others in common usage, was originally from the Old Farmer’s Almanac. And this publication chose the names it gave to the moons from the ones used by North American tribes, mostly those of the Algonquin.

In fact, the April full moon is not named after the colour itself, but a wild flower native to the eastern parts of North America that blooms around this time. Phlox subulata, also called creeping phlox and moss phlox, was generally known as the moss pink.

Other references to spring abound in the alternative names for this moon in different cultures. Here are just a few: Moon When The Ducks Come Back (Lakota), Moon When The Streams Are Again Navigable (Dakota), Moon When The Geese Lay Eggs (Dakota), Frog Moon (Cree), Breaking Ice Moon (Algonquin).

The Celts are said to have chosen names like Budding Moon, Awakening Moon, New Shoots Moon, Seed Moon and Growing Moon, though I suspect some of these are recent ideas (and why not?!). Fiona Walker-Craven in 13 Moons and Michael Howard in Liber Nox both give Seed Moon.

Looking around me here at all the freshly-turned fields I could perhaps choose Warmed Earth Moon. But I think I would go for Alexanders Moon. This wild wayfarer has sprung up on all the hedge banks with a vibrant audacity, suddenly bursting out into sappy flower, its angelica scent pervading the lanes.

How about you? What would you choose to reflect your April landscape?

Stories in the Hills (detail): resin, vintage buttons and paper.

Ada’s buttons

People say that Norfolk has no hills. In fact, as you will know if you’ve tried riding a bike anywhere to the north of Norwich especially, there are far more ups and downs than you might think. My archaeologist husband was a great one for pointing out long, long views with horizon line after horizon line from the high points that he was uncannily aware of at all times.

Years ago, as part of my Howe project (Howe means burial mound) I found over 400 named hills on Ordinance Survey maps of Norfolk. And that didn't include any that were named after the nearest village! (I’ve actually found more since then.) There were lots of evocative ones — Crow Hill, Wormwood Hill, Candlestick Hill — and recurring ones like Gallows Hill and Gibbet Hill whose tales are clear enough.

For an exhibition in Salthouse church I taped a giant copy of Faden's beautiful 18th century map of Norfolk to the floor, with Salthouse at the centre. I made resin hills in cupcake moulds to place on the map. Cake-shaped to echo the sweet offerings to spirits and ancestors traditionally made in such places. A button from my grandmother Ada's button jar embedded in each one to represent the human stories deep inside every hill.

My grandmother Ada used to knit squares to sew into blankets. I don’t know whether she actually ever sewed them together or what happened to the blankets. I do remember noticing, even as a child, that the squares were quite rough and messy and of varying sizes.

Nana wouldn’t have dreamed of buying a ball of yarn from a wool shop. OH no. Every Saturday afternoon there would be a different local jumble sale where she would scoop up old woollen jumpers for pennies. Once home she would unravel the garments, pulling at the end of the yarn until it danced its zig zag jig along the rows and the garment it was attached to grew smaller and smaller. As she went along she would wind the wool into balls that always remained stubbornly wild and crinkly. But what happened to all the buttons? Until my grandmother’s bungalow was cleared I had no idea. But there they were, two big sweet jars full of twinkling treasures in every hue, shape and size.

Those jars became mine many years ago. I delighted in washing the buttons - and oh how they needed it - swishing them through the water and swirling them around on newspaper to dry. Then came the fun of sorting them by colour and material (some were wooden or metal) and enjoying the sight of myriad shades of turquoise or purple or blue as I slid them into clear bags and boxes.

My favourite buttons, though, were the mother-of-pearl or iridescent ones. These sat in their bag for years until I had the idea of using them to rescue a strange, gone-wrong weaving and felting project. I’d put so much time into this failed experiment that I didn’t want to throw it away. So I fashioned it into a circle and started sewing Ada’s beautiful old pearly buttons all over it without having any idea of what I was making or why.

There are gaps still, but I think I will try to finish it. Then, just maybe, I’ll know what it is that I’ve conjured from Ada’s pearls.

Crow, rook or raven?

Up here, in a stone barn

this Easter, a straggle

of children and adults saw

the outlawed story retold

of an old resurrection:

a grain reborn as a child

(as we sat in the straw):

a lost child fostered and found

to be wizard of poets, a star

with the wind’s protection.

Out in the yard, our cars

mud-axled, we dispersed,

turned away from the scene.

Now I visit my alder stream

in a double life, knowing

that nothing’s been lost. A raven

croaks Brân overhead:

banished westwards, but still

surviving. And alder flowers

green as thieves, still growing.

Hilary Llewellyn-Williams, from Alder (March 18 - April 14), in The Tree Calendar sequence

If you’ve seen any of my videos on YouTube you will know that the woods, heaths and streams around my cottage all have special names which they’ve shown to me one by one. The area of heathy woodland on the other side of the road is Crow Wood, and needless to say there’s a good reason for this.

Crow Wood is, in reality, just a small area of open access woodland but somehow it’s quite easy to become disorientated and wonder whether you have ever followed this or that track through the birches and bracken. To me, it’s a magical forest. The fact that it’s bordered by fields and streams probably accounts for treasured sightings of red deer and the ever present cawing of crows. We don’t have ravens in Norfolk yet - as far as I know - although they are heading this way and have been recorded just over the River Waveney in Suffolk. So any large corvid you see will be either a crow or a rook, and their sounds and behaviour are quite distinct from each other.

Often I hear a chirruping and will run outside to see a cloud of rooks passing over, preparing to roost in the alder carr or somewhere else across the fields from here. But the purposeful ‘caw’ of crows is quite different, and is often the first sound I hear from my bedroom in the mornings.

Like the deer, they seem partial to the pastureland right at the bottom of Crow Wood and I once saw an enormous crowd of them gathered among the tussocks. The sounds they made were so expressive that they had to be heard to be believed, but reminded me of the rise and fall of heated discussion. I wished afterwards that I had thought to record what happened but on reflection, perhaps it’s more fitting to let the crows keep their own counsel.

On the acres of farmland on either side of Old Lane (its actual name), fields stretch away in all directions and I love catching the gleam of corvid plumage as crows and rooks - but mostly crows it seems - strut around in the furrows, like black pearls against the roughness of the turned earth. It’s then that I remember with delight that I live, more or less at least, in the part of Norfolk that some archaeologists and historians believe to have been the centre of a Romano-British corvid cult.

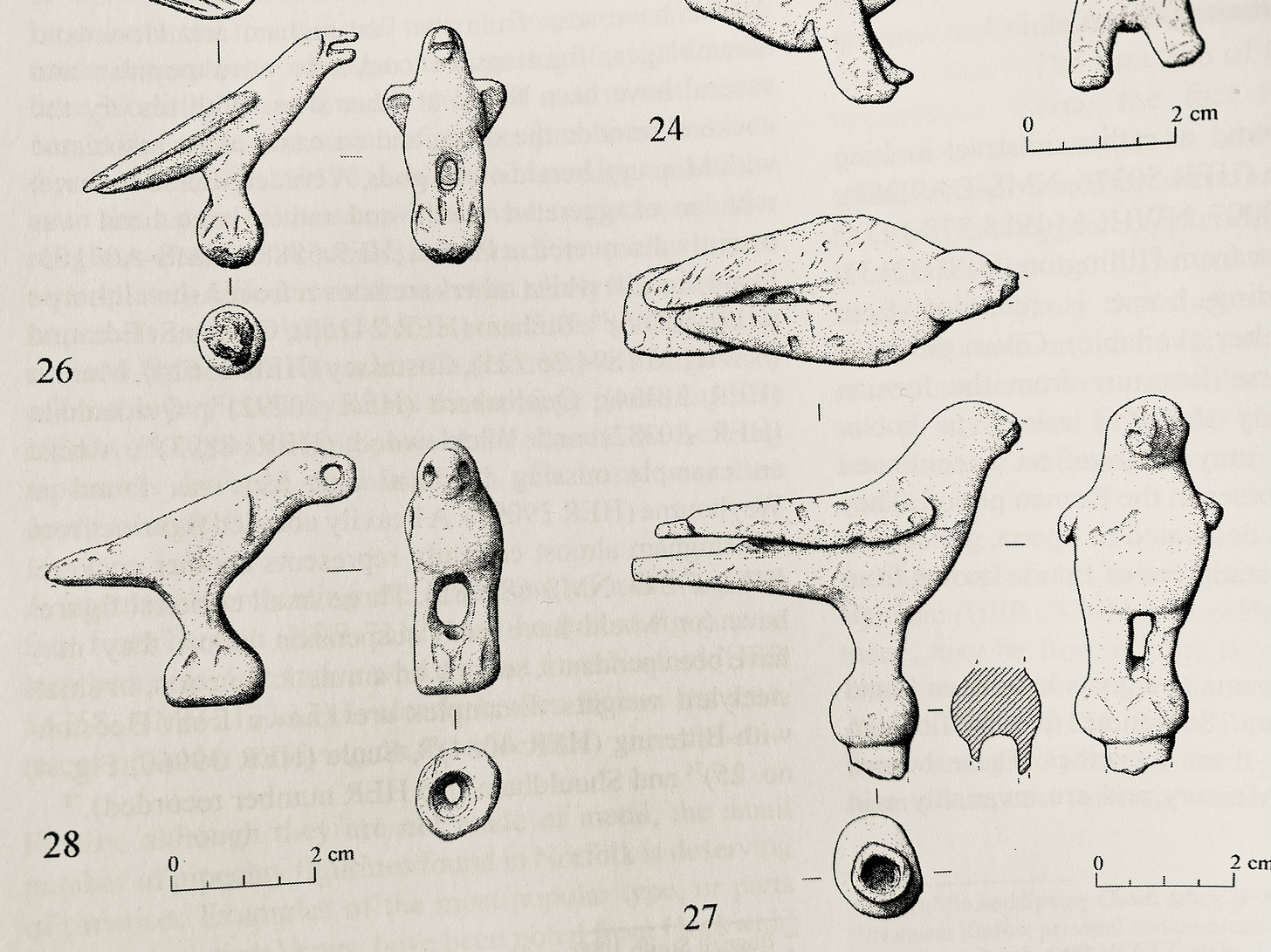

But why would anyone think that corvid-shaped metalwork objects could be connected with a religious or ceremonial cult? The clue is that they seem to have been mounted onto spiritual implements.

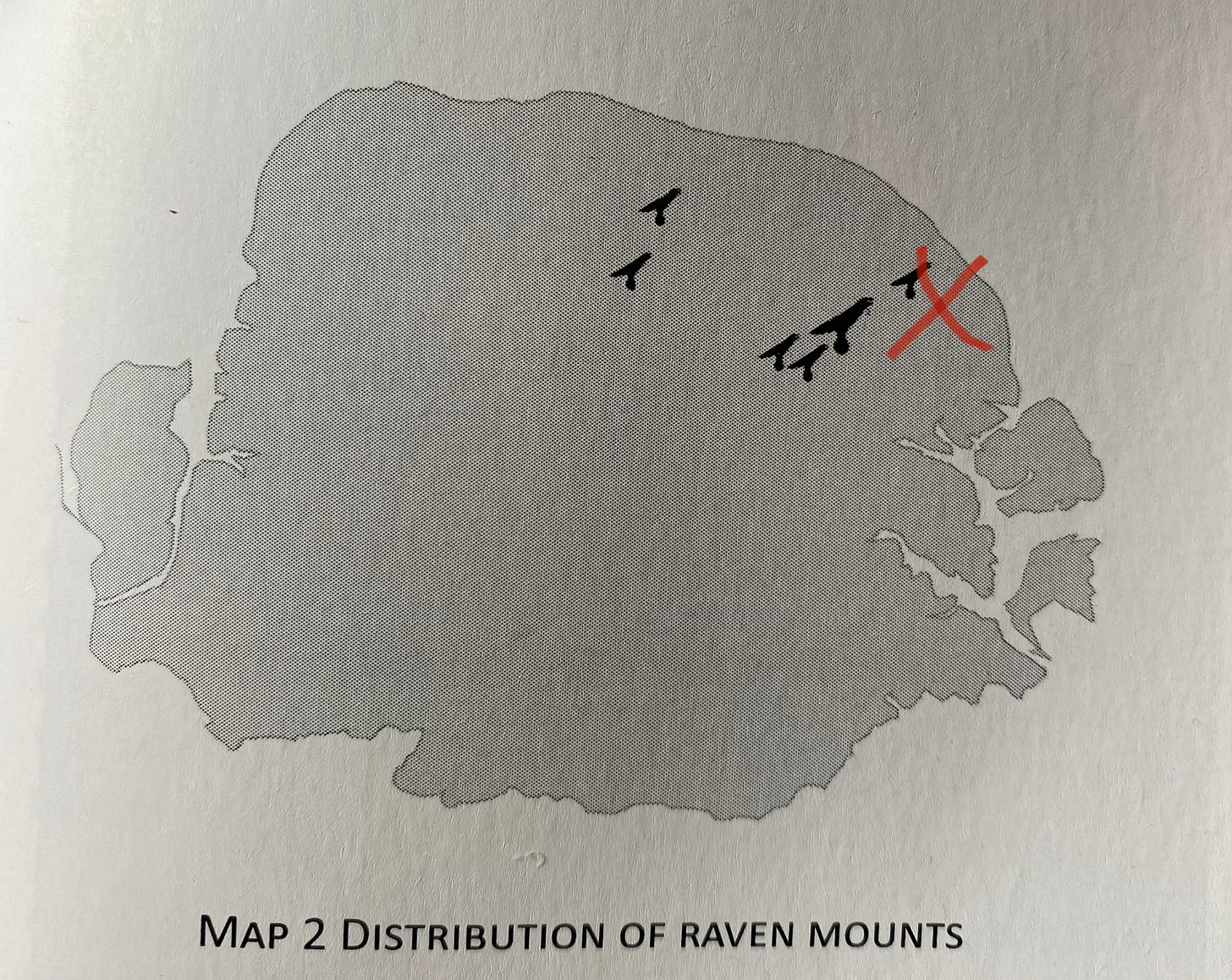

Find spots of the ‘crow cult’ ceremonial objects. The cross marks the approximate location of my home (and Crow Wood!).

Similar figurines have been found in the parishes of Felmingham, Paston, Burgh with Tuttington, Briningham, Letheringsett and Aylsham, all in north-east Norfolk. Clearly corvids, most of them sit on a sphere and carry another smaller sphere in their beak. They have traces of an iron attachment inserted into the base, and the Felmingham examples suggest that these are the remains of iron sceptres which the birds topped.

While some academic papers and museum labels describe the birds as ravens, the truth is that no-one actually knows which corvid is intended in the mysterious objects. There is a Roman fortified port at Brancaster in north-west Norfolk, and Bran means raven. But having said that, even those who posited the cult have to concede that quite some distance separates Brancaster from the very tight area from which the corvid figurines have been recovered.

I like to think of them as crows.

It must surely be significant that examples of the raven [sic] figurines … discussed above have only so far been recovered from an area of north-east Norfolk. This suggests a closely defined area in which a particular god held sway. Most likely this was a local cult with its origins quite probably going back to the Iron Age. The god Apollo, or a local version of this god, seems to have been the subject of this worship.

Adrian Marsden, Satyrs, Leopards, Riders and Ravens in Landscapes and Artefacts: Studies in East Anglian Archaeology

Just a few of the Romano-British iron corvid mounts.

Ground elder & cow parsley

Oh to be in England

Now that April’s there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf

Round the elm tree bole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England - now!

Robert Browning, from Home-Thoughts From Abroad

As a dreamy child with the incredible good fortune to have a big wild garden outside the back door, I remember wandering around it early in the mornings before school reciting this verse to myself. Maybe out loud, too. My brother, though only three years younger than me seemed far away both in age and interests (lego, and making models from cardboard boxes) and I must confess I didn’t even think about what my parents might be doing.

I knew the next verse of the poem too, the one that begins And after April, when May follows … but less well and without the breathless excitement that those initial lines conjured in my heart. April in our garden was magical. The snowdrops and aconites, so eagerly sought in February, might be over but there were primroses, daffodils, violets and lungwort if you knew where to look for them.

There was even a big elm tree that sprang into leaf exactly as the poem describes, which seemed to me pure sorcery on the part of Robert Browning. That is, until it was tragically struck by Dutch Elm Disease. But by then I was obsessed by David Bowie, Cockney Rebel et al and its loss cut less deeply than it would have done a few years before.

It wasn’t the sort of garden to have neat beds. My dad wasn’t a gardener over and above mowing the lawn and making compost from guinea pig bedding, and my mum had realised long ago that this garden needed to be left to do its own thing. Her long hoped for greenhouse and vegetable garden just weren’t going to materialise with all trees and shade. And the ground elder and cow parsley everywhere! I loved both and still have the sharp, sappy scent in my nostrils as in my mind’s eye my dad scythes a path through the green.

Found!

The Well of the Little People - a Good Friday tradition

We were in west Cornwall, following the silvery thread that I always feel links our eastern lands with those of the far south-west. We often spent time at the prehistoric monument of Men-an-Tol, and I had been aware that there was said to be a holy well very close by. This was Fenton Bebibell, an ancient site in Morvah parish, whose name translates to ‘Well of the Little People’.

Until the 1920s, each Good Friday it was the custom for local children to bring their dolls to the well to be 'baptised'. The procession of children would make its way across the heath to the well, where their dolls were immersed. No one knows how old the tradition is, but it is likely to be an echo of something very ancient. Now of course the 'little people' for whom the well is named might equally refer to the children, or to the dolls, or to the Fair Folk themselves whose favoured day, it is said, is Friday.

Sadly, the well became overgrown and was lost for decades. No-one was able to locate it for certain. Eventually, by good fortune, members of CASPN (Cornish Ancient Sites Protection Network) discovered and cleared the well, and the 'dolly dunking' custom was revived in 2006. It has taken place on Good Friday every year since then, with volunteers taking the opportunity to cut back the vegetation leading to the well, and to clear the pool.

Googling 'Fenton Bebibell' leads to local newspaper reports and photographs of children and their dolls from several recent Good Fridays. In one report I read that the baptism is followed by Easter goodies and mead!

So it was that the next time we were in the parish we asserted a firm intention to search for Fenton Bebibell ourselves. We had read that the well was still notoriously difficult to find, but we were fairly confident, as we had an OS reference to work with. Not only that, but we had a shiny new GPS which was raring to be put through its paces. What could possibly go wrong?

Setting off down the farm track beyond Men-an-Tol, with the notched mass of sacred Carn Galver an ever watchful presence, we duly arrived at a stile and a path through heather and bracken which we expected to lead to the well. Some time later, we had traced and retraced the grid reference, set and reset the GPS, scratched our heads, gone separate ways and come back and scratched our heads again. There was absolutely no sign of the well, and no clue as to where a water source might lie.

It was May, not so long after Good Friday, but already the portal had clicked shut and the vegetation had closed over again, keeping its secret safe. As we clambered over tussocks and squeezed through low gorse thickets we knew from the grid reference and GPS that we must be close.

We searched and searched. We asked the Otherworldly ponies who had materialised from nowhere. We split up again and searched individually. We searched again together. On the point of giving up, we decided to sit in the heather with our flask and have a cup of tea. Then we agreed that I would just have one last look while Trevor waited.

A gate lay below us and, although according to the map reference it would take us away from the well, I wanted to see where it led. As I approached it I could see a strange twisty thorn and had a feeling that we were now on the right track. Climbing over the gate I scanned the boundary line and oh! large stone slabs and a musical trickle of water beneath!

There, nestled under the hedge, was Fenton Bebibell. I'll never forget the sense of achievement, of excitement, of elation we both felt as we reached the sparkling pool.

The Well of the Little People!!!

I let out a shout and Trevor came running, or as close to a run as is possible when traversing clumps of sedge and bracken. There was no mistake. Quietly we each interacted with this magical site in our own ways, and instinctively I drew out my drum and the beautiful hare platter that was coming home with me this time, and placed them on the largest stone above the pure flow of the well.

True, it wasn’t Good Friday, but here we were at the holy well, where the spirits fairly danced around us, so what better place to give my drum and my hare a magical boost?

The energy fairly fizzed! I now know that this spring is the source of the River Newlyn.

Turning away from the well towards the fairy thorn, and with sacred Carn Galver up ahead, my gaze was caught by something strange. I jumped as I realised that I was being stared at. A closer look revealed the secret of the thorn. Two little people - were they well-maidens or tree spirits? - that were almost a part of the twisty, lichen-covered trunk. Who had put them there and why? Not that I wanted or needed to know. This was strong magic.

Two wildlings.

As we walked back towards the main track, a black horse gradually approached us. The horses are generally very shy, but this one seemed to want to tell us something. When the horse got close to us, it turned and slowly led the way back down. We followed. and came upon this Otherworldly gathering of magical equines among the bluebells. We felt that they were part of the story, too.

Led by an Otherworldly horse to meet his friends among the bluebells.

The Easter hare spell

Here again is the Yorkshire wisewoman, grandmother of Claire Nahmad who wrote Earth Magic. We were first introduced to her words in But A Wild Mother and I have a feeling she will make a habit of jumping into our newsletters from time to time to impart her teachings. She says:

‘The Easter hare spell is best essayed by the light of the full moon of March or April. As soon as the evening light has all but stolen away, you must make your way to the edge of a field or a meadow (or if you are a town-dweller, you may sit alone in your room and contemplate the picture of such in your mind) and so that you may have good health all the year round, and cast off any ailments that afflict you, speak this rune aloud to the hares that live in secret and run by night thereabouts:

Hare spirit, swift as lightning

The devils in me need affrighting

Brightest angels in high heaven

Fright them from me seventy-times-seven

Now do they reside in you

Run, run hare spirit, till fall of dew.

This is not to curse the hares with your maladies to make them sick, but to translate them to the hares so that they may carry them off for you, and so purify them.

When you have done, hurry home and light a white candle on the cusp of Raphael’s hour, which is one hour before midnight. Draw a hare on virgin paper and inscribe it with those afflictions you wish to be rid of. Then burn it up in the candle flame, repeating the rune as written. Give thanks to Raphael and to the hare spirit, and light a bowl of incense to burn alongside your candle.

Now meditate upon the swift and graceful hare, and let your soul take flight. Pass it into the hare, and let it run free and fleet in the form of the hare; let your soul run wild and unfettered over the wide meadows and upon the open hillsides as often as you feel nervous or full of frustration and weariness, and you will keep your spirits sparkling and childlike as if they lived in an eternal springtide. Do not forget this teaching, for it is an old trick of the witches.’

A blessing of blackthorn

One of my favourite childhood books, which I vividly remember wrapping around myself when I was eight (the same age Nona, the heroine) is Miss Happiness and Miss Flower, by Rumer Godden.

During the course of the exquisitely-told story, the reader learns a great deal about Japanese culture and I have never forgotten the wonder and respect I felt at discovering this completely different way of life from my own. The book was written in the 1950s, relatively soon after the events of the Second World War, but nothing of this enters into the narrative. Instead, we learn of an ancient and beautiful culture which at that time was probably still fairly intact.

Without giving too much away, I will just say that Nona’s teacher ends up bringing her a gift. Two tiny scrolls, hand-lettered, inscribed with haiku. We’re told that these are to be placed in the household niche, the place of honour within the home, and changed with the seasons. These scrolls are dolls’ house sized.

I even remember the haiku, and often find one or other of them in my mind. Here is the spring one:

My two plum trees are

so gracious. See, they flower

one now, one later.

Scrolling back through my instagram account I noticed a post that I wrote about the blackthorn along the lane on 5 April 2019. Exactly four years later with blackthorn again flowering, I tried to turn my memory into poetry.

A writing prompt had inspired me to attempt a group of three haiku, and this was something I’d never considered before. Three times three lines making a magical nine! I put aside my fear that I was rusty, that my poem wouldn’t do justice to the enchantment laid out along the lane, and started writing my spell.

Just as night comes down

blackthorn blossom seems to burst

from bare wintry boughs.

Those tightly furled buds

fistfuls of constellations

tossed into the twigs.

Little shooting stars

explode in showers of stamens:

gold trails in the dusk.

Blackthorn at nightfall, 5 April 2019.

A few resources

John Clare, The Shepherd’s Calendar, first published in 1827. Many editions are available and it’s highly recommended as a snapshot of rural life 200 years ago. My copy is published by Oxford University Press, 1973 with woodcuts by David Gentleman.

Claire Nahmad, Earth Magic: a wisewoman’s guide to herbal, astrological and other folk remedies, Rider, 1993.

Hilary Llewellyn-Williams, The Little Hours, Seren Books, 2022.

The ‘Crow-Cult’ theory:

Adrian Marsden, Satyrs, Leopards, Riders and Ravens (pdf ) and also within Landscapes and Artefacts: Studies in East Anglian Archaology, Archeopress 2014.

YouTube channel, for glimpses of Crow Wood and (sometimes) corvid calls for good measure :)

Imogen thank you for this lovely post, I have been reading it over a late breakfast. I am originally from Cornwall and never knew about the well of the little people, I will seek it out the next time I am there.

Love your 3 haiku to Blackthorn, they describe her so beauty and presence so deliciously.💚

One thing that interests me about naming moons is that the old tradition ( at least I know it as old!) of naming moons seems to be largely forgotten, that is to say that a moon is not named by the calendar month but rather by when it falls in relation to the winter solstice.

Meaning that the first full moon after the winter solstice is the start of the naming of the moon cycle and this may fall in either December or January, thus each moon name has 2 months it may be in.

I call this current full moon, birthing moon ( which can be March or April) and very much associated with the budding and flowering of Blackthorn.

From my recent recollection the moon has been mostly in March and Blackthorn has been in flower because it has been warmer and sunnier and this year Blackthorn is flowering in April because of the cold weather. Maybe coincidence or maybe the moon knows a thing or two?😊

🌛🌕🌜

A lovely read, thank you. Here in Wales there’s a town nearby called Cwmbran, which translates as crow valley. There are indeed a lot of crows, rooks, jackdaws and ravens around here. Jackdaws will often flock with crows and it’s easy to tell the difference in flight - just remember, crow slow and jack flap and you’ll see what I mean.