Sign of the season: cuckoo pint (lords and ladies) with its startling red berries. 23 July 2024.

Hello, and welcome to this late July just-slightly-past Full Moon edition of Bracken & Wrack.

Along the lane in this hidden corner of north east Norfolk, the shifting of the season is palpable. Pink and white blackberry flowers give way to tightly packed berries, the first willow-herb spires are opening, mugwort flowers have burst into untidy sprays in a perfectly wild way. Tiny and poignant, the first fallen conker-cases lie ground into the tarmac where rare car tyres have passed over them. The purples and golds of thistle and ragwort now catch the eye where, until recently, all was green. As sweet and as floriferous as ever, the wild honeysuckle or woodbine trails, spirals and tumbles joyously over everything else. It’s always thrilling to take an evening walk just to breathe in the heady musk of its trumpets. A posy of woodbine is said, in folklore, to bring a maid ‘tender dreams of love and passion’ and it’s also held that if you bring honeysuckle into the house a wedding will follow on its heels. You have been warned - or given a useful tip!

In this issue you will find:

A seasonal poem by Laurie Lee

Folk customs from a 1930s fenland childhood

The Blackberry Picker - part 2

The Key to the Sycamore

The Saint with a Scallop Shell

Saint James’ Pilgrim Biscuits recipe

Saint James, Staggerwort & the Witches’ Sabbat

Thistle, blue bunch of daggers

rustling upon the wind,

saw-tooth that separates

the lips of grasses.

Your wound in childhood was

a savage shock of joy

that set the bees on fire

and the loud larks singing.

Your head enchanted then

smouldering among the flowers

filled the whole sky with smoke

and sparks of seed.

Now from your stabbing bloom’s

nostalgic point of pain

ghosts of those summers rise

rustling across my eyes.

Seeding a magic thorn

to prick the memory,

to start in my icy flesh

fevers of long lost fields.

Laurie Lee, ‘Thistle’

(Press play below for an audio reading of ‘Thistle’)

Thistle on the heath, 23 July 2024 - a little early for its ‘smouldering head’ and ‘sparks of seed’.

A 1930s FENLAND CHILDHOOD: Folk Customs

Time now for the next part in the series I began in Dissolved in Dew, inspired by the contents of ‘Poultry, Plums and Fen Runners’, the memoir written painstakingly and determinedly by my mum Sylvia Yates (née Ashmore) (1927-2023) in the last years of her life. It was my brother who put all the material together into a homespun volume for her and printed a handful of copies for family members. You can read there about why I thought parts of it might be of interest to Bracken & Wrack readers.

The whole idea was kickstarted when, in The Emerald Sun, I wrote about a Fenland horseshoe-nailing practice that may just possibly have survived from the time of the pagan Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

One thing that surprised me in Sylvia’s memoir was the section on Fenland folk customs. During my own childhood I was aware of only a few of the ones she mentions, or at least I was probably aware of them but never realised that my very matter-of-fact mother placed any credence in them. I certainly didn’t know that she had picked up her knowledge from her mother and grandmother. If I had, I would have pricked up my ears. Especially so, since my great-grandmothers were both born around the 1860s at a time when the ways of the deep Huntingdonshire fen folk (and indeed Norfolk folk, as my maternal great-grandmother Harriet Pepper was actually born over the border in my own home county) had probably remained unchanged for generations.

Some of the beliefs and ways Sylvia cites are probably quite universal as I have seen repeated mentions of them in collections of folklore and elsewhere. But even the familiar ones are interesting to have verified as living practices during the 1930s.

I think you will probably recognise quite a few of them too.

With so many plum orchards around my grandparents’ home, Sunday lunch pudding was more often than not plum pie or just stewed plums and custard. From my own childhood, I remember counting the plum stones left on the edge of my pudding bowl. You would find out when you were going to be married by counting this year, next year, sometime, never until you ran out of stones, and silk, satin, cotton, rags to see what your wedding dress would be made of. Then there was coach, carriage, wheelbarrow, muck cart for the mode of transport. And you would discover your beloved’s calling in life by counting tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, rich man, poor man, beggar man, thief. That’s so awful isn’t it, but by the time I was growing up it was just a ritual to keep the children occupied once they had finished their meal. Clearly meant only for those seeking a man, and to be married, but I suppose in the dim and distant past that was how it was and not necessarily questioned.

Another of the customs my mum mentions that I do remember, although just done as a bit of fun at Halloween, was trying to peel an apple in one piece and throwing the peel over your left shoulder to see what letter you would find (well, with a bit of imagination). This would be the initial of your sweetheart.

So here are some of the others; yes many are indeed familiar but I am just very interested to know that they were being passed down through a family’s female line right through to my mum’s time, although it wouldn’t have occurred to her to instil them in me or my brother. How many more families is that true of?

My great grandmother apparently used to say Wear green for a wedding and you will soon be wearing black for a funeral, or just Green today, black tomorrow which I suppose indicates green being generally unlucky as a clothing colour. Well as a lover of the greenwood it’s one of my favourites, so I shall have to take my chances ;-)

In Fenland villages all the curtains were kept drawn in a deceased person’s house and those of all their neighbours along the road to the church. All the traffic stopped, people on foot stood still and men removed their hats or caps until the cortege had passed. My grandparents’ village like many others had its own bier that was pulled or pushed by hand to the church. Sylvia says that a coffin path existed in the neighbouring village of Bluntisham leading from the village to the church to avoid houses and pre-enclosure fields. Why ‘pre-enclosure’ fields she does not say, but what a fascinating thing to ponder.

So let’s look at good and bad luck omens, invariably significant in folklore. Seeing a black cat is always good luck, and a bee flying into the house means you can expect a visitor. Swinging a tiny money spider around your head brings good luck, although maybe not for the dizzy spider. Good luck also follows if you leave garments put on inside-out like that all day. Horseshoes nailed horns-side-up and strings of holed stones also bring good luck. (Of course we knew that, but here it’s a Fenland custom of which I wasn’t aware. Huntingdonshire is a long way from the seashore, the usual place to find holeystones.) An elder bush in the garden brings protection from lightning, although its wood should never be brought indoors. Another anti-lightning measure is to cover all cutlery, metal objects and mirrors in a thunderstorm, which Sylvia says my grandmother always carefully did.

As for bad luck, to prevent it you must turn the money in your pocket when you first see the new moon and also make sure to avoid looking at the new moon through glass (oh I remember that).

Do not thank the person who picks up a dropped glove for you - now that’s a strange one. Crossed knives on the table, two people attempting to make a pot of tea together, crossing on the stairs: well, just don’t do it. According to the lore, nothing can prevent seven years’ bad luck if you break a mirror, nor the ill effects if you forget to throw a pinch of spilt salt over your left shoulder.

The weather forecasting my mum mentions seems fairly standard but she says that everyone knew Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight. Red sky in the morning, shepherd’s warning and that if cows are lying down in their field, rain will follow. Rain was also foretold by a ring around the moon, swallows and martins flying low or a cat licking a paw to wash behind an ear.

You would also look out for the tiny scarlet pimpernel flowers seen on waste ground. This plant is known as the poor man’s weather glass with good reason. Everyone knew that its brick-red flowers open and close with changes in the weather. I knew that too, actually, but I wonder to what extent those little bits of useful knowledge filter down these days?

Horns-side-up horseshoe - a very old one, probably one of my great-grandfather’s.

THE BLACKBERRY PICKER - Part 2

The last edition of Bracken & Wrack saw the first part of an essay I wrote a couple of years ago at around this time. Finding it again I was prompted to share it with you here, and I thought it would be best to divide it into parts as it’s quite long. I’ll start with the last few words from the first instalment to set the scene, and then we’ll get going. I hope you have plenty of juicy blackberries forming in the wild places and wastelands (including the most unlikely urban sites) where you are.

Part 2

‘Anyway, I’m off to the beach for the day with the little one’, she continues. ‘It’s too hot for her on the heath.’

I’d first assumed a child, but she seems too old. A grandchild? Of course; a dog! Sure enough I glimpse a small furry face in the passenger seat.

‘Have fun!’.

‘Oh, we will!’, and she’s off, leaving me wondering whether she will actually get around to picking in the lanes of East Ruston and whether you ever got lost if you lived there.

Now read on ….

Another time it’s my stern-faced neighbour, the one with the swallows. Approaching each other head on, there’s no option but to say hello and try to smile (there’s a history here). I’ve stopped picking but my partly-filled colander with its gleaming purple cargo tells its own story. That primal worry rears up again: if she catches me in the act, the next time I run my hands over the bushes there will be nothing left. Amazingly, she too is surprised.

‘Oh, are they ready? I’d assumed they would be all dried up to nothing again this year.’

Surely she must walk her dogs on this lane at least twice a day but she actually hasn’t noticed the heavily laden briars; the bounty they carry. It’s unimaginable.

‘Well, lots of them ARE dried up’, I say truthfully, though finding myself not wanting to sound too enthusiastic about the quality of the berries. ‘But’, I go on more charitably, ‘there are some surprisingly good ones too.’

She nods and passes by, her yappy little Jack Russell straining at the lead and rearing up to try to get to me. No doubt to snap at my ankles.

In fact, there are easily enough for us all. The thing with blackberries - and nature has surely designed them that way - is that not only do the berries in a single cluster ripen sequentially but the bushes themselves vary wildly in coming to their peak. I read somewhere that there are an unexpectedly large number of wild blackberry varieties, each with a differently timed life cycle. Yet we lump them all together, conveniently and often disparagingly, as ‘brambles’.

And I really think that nobody but me is picking on our lane. Nobody.

Another morning and another neighbour; friendly, younger, pink-haired. Walking her dogs, of course. She stops, too, when she sees me. She’s much smilier.

‘They’re so dry, aren’t they? All dried up to nothing on our driveway’.

She means the track onto the heath; her home is a beautifully renovated cottage on the heath itself. A glorious, enviable spot. But even she hasn’t noticed this year’s treasure.

‘Oh, actually there are loads when you look’, I hear myself say.

‘I normally take the dogs out in the car to the woods, but it’s too hot for them to run there today so I’m sticking to the heath. I tried giving him’ - indicating one of the dogs - ‘a blackberry but he spat it out. She likes them though’.

The other dog gazes wistfully at my blackberry bowl. I give her a blackberry which she drops immediately and the three of them turn down their home track. I’ve noticed that the blackberries are especially big and juicy around her cottage sign. And although I think of the heath-dweller as a bit of a kindred spirit, she seems not to have even registered their existence.

********

It’s evening. My restless feet and mind take me towards the back door again, colander in hand. Once I would have taken a tupperware but one of the subtle shifts I’ve sensed is of simple beauty in the everyday; making the mundane a ceremony.

Not that collecting blackberries is mundane. If I have a heightened appreciation of what a handmade, tactile container can bring to the task, my wonder at the wild bounty of the blackberry harvest has been with me as long as I can remember.

Certainly, as a child I went out with my mum scrabbling around the edges of the woods or the tangled banks of the Old Cricket Ground. We would not have taken artisan kitchenware, no. Tupperware or perhaps a plastic colander would have been the order of the day. And although the sight of the glistening, purple-black clusters would have pleased my eye and my heart even then - especially set against leaves just beginning to show golden, russet and plum around the edges - I don’t remember there ever being an abundance as there is this year. The haul was invariably smaller than the capacity of our ambitious collection of containers, and even a handful felt like a gift.

At 10 years old I joined the Guides. The Scout Hut where we met each Tuesday evening lay down a heavily-cratered unmade track, littered with flint. In the summer and early autumn when it was still light we would sometimes hike to the old gravel workings known as ‘the pits’. Arching brambles lined the way, trying their luck in every uncultivated corner between the bungalows and prefabs. Part of the route followed the old railway line, and I vividly remember the dusty sleepers and the strong opinions flying around concerning the merits or otherwise of ‘This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both Of Us’ by Sparks.

The rusted tracks were overhung with brambles too, and I gleaned more picking lore from my friends. The super-sized berries at the end of each cluster were called King Berries and they were, naturally, especially prized. Traditionally, and probably literally, these were the first to ripen and had the most heavenly flavour, so it was common to find them all picked off, leaving the smaller, harder fruits behind.

I never ate a berry while we were picking. I don’t now. Partly, I suppose, it’s ingrained in me not to eat fruit or vegetables without washing them. Although, given the questionable chemical content of tap water, that reasoning doesn’t entirely convince. Mostly though it’s the texture of the raw berries which for some reason repels me a little, much as I love the flavour. It’s a trait that stood me in good stead as a teenage strawberry picker. After all, each full punnet was worth a whopping 25p as long as it set the scales bumping down, and didn’t contain too many telltale green stars nestled between the plump vermilion berries.

I balance the colander on one hand as, in a practised movement, I pull the ill-fitting door firmly closed behind me. This effortful manoeuvre with balanced bowl and makeshift doorstep is steeped in danger for a patently non-sensible blackberry collecting container. But all goes well this time, and I crunch across the yard.

The colander is heavy even before I begin, but I don’t care. It has served me well day after day these past few weeks. Now, dusk is falling. It’s definitely darker than I would like, colours already beginning to merge.

I should have known better. Every evening now, sunset moves relentlessly forward while the dry heat of each day deceives us into believing we are still in the heart of midsummer, dancing to its beat. The gilded bracken - already browning and crumpling - tells us otherwise.

It is still eerily warm as I set out along the lane, trainers sticking a little to the tarmac and the pale blue cardigan I’ve thrown on over my dress feeling like a miscalculation. As is my timing. It really isn’t easy to distinguish the good berries from those not worth the picking. Always, it’s the feel between forefinger and thumb that tells you the most. That perfect degree of give is something I learned to judge half a century ago. But in this light I can’t see the gloss, or lack of it, nor whether each berry is pinched tightly into itself or a freeform explosion waiting to happen.

Believe me, the clues are all there before ever you get to the place where your fingers meet with a sickening squelch and a mess of berry squashed between them, trickling overblown sweetness as a libation to the nettles beneath.

I rarely prick my skin. Those same decades of experience tell me which of the tempting clusters are simply not worth the risky acrobatics required to garner them. Needless to say, these are always the biggest and juiciest ones. Each berry is a swift calculation. Will the tips of my fingers slip through that gap without being impaled?

To be continued …

‘Riddle-me, Riddle-me, Ree.

In my pocket I carry a key …’

So sang the West Wind as he blustered through the wood, with his hair flying and his fingers jingling something in his pocket.

Little John Bunting stood still, listening to the Wind’s voice. He scratched his head thoughtfully, and tried to guess the riddle-me-ree, but he couldn’t find the answer.

‘I gives it up,’ said he, and he turned his back on the Wind and walked towards home.

Riddle-me, Riddle-me, Ree.

Twill unlock a sycamore tree’,

chanted the West Wind, blowing John’s hair awry, and throwing a bunch of sycamore keys on the ground as he flew by.

Alison Uttley, ‘The Keys of the Trees’ (extract from short story) in Magic in my Pocket

Not quite ready for the West Wind, sycamore keys on the lane 22 July 2024.

THE SAINT WITH THE SCALLOP SHELL

Here we have lovely St James, who has lived on the painted screen at Belaugh in Norfolk for the past 500 years. He adorns many other medieval screens too, being one of the twelve apostles and especially beloved of those who traverse the seas. St James holds aloft his customary scallop shell, the wearing of which on a hat or cloak became an emblem of those away on pilgrimage. Some say that the lines on the shell symbolised the paths from all points of the world to the shrine of St James, and some that it signifies the shape of a sunset at the world’s end - in other words, the shrine itself.

St James and his scallop shell on the medieval rood screen at Belaugh, Norfolk.

I hadn’t realised until I looked it up that the shell had a practical purpose too, as it could be used as a simple lightweight bowl for eating and drinking on the road, and it was also used as a measure and scoop for food donations received along the way. How lovely to think of a gift from nature being repurposed in this way.

Once at Compostella, scallop shells could be picked up on the nearby shore to take home as mementos, but human nature being what it is, there was also a thriving trade for them in the shops around the shrine.

Best of all are the stories telling how St James came to be associated with the shell. One of these relates how the saint rescued a knight who was clothed from head to foot in scallops; another that a scallop-covered knight and horse mysteriously rose from the waves while the saint’s body was being transported from Jerusalem to Galicia. Now these are the kind of tales we like here at Bracken & Wrack :-)

The Feast Day of St James will be upon us very soon, as it’s celebrated on 25 July. Apparently, on this day it’s traditional to start eating oysters, although the oyster season proper doesn’t begin until September. We’ll come back to the oyster in the next Bracken & Wrack, but of course an oyster shell does resemble the cockle or scallop shell and in past times oysters were very commonly eaten by everyone in society as they were so numerous around the coastline.

Interestingly, in Walking the Tides, Nigel Pearson tells us that the scallop shell was anciently the badge of those who felt connected to the divine feminine principle, especially those powers who had influence over the seas and the waves. It may be fanciful to try to find a connection, but it’s certain that the need to petition for protection and good luck must have been strongly felt by medieval pilgrims as they took ship from such ports as Great Yarmouth in Norfolk or Dunwich in Suffolk.

SAINT JAMES’ PILGRIM BISCUITS

This recipe is an outrageous anachronism as most of its ingredients would have been unknown to the average medieval pilgrim. But it is in the spirit of the open road that I offer it here. It’s one of those useful sweet snack recipes that is both easy to put together when the journey calls and doesn’t result in a gooey or crumbly surprise when you open up the provision package. On a recent pilgrimage around Avebury we came back to a tupperware of these that had been forgotten about and they were still fresh and good. And very welcome at that moment with a compromise coffee-bag coffee, I can tell you. The recipe is based on a Deliciously Ella one, and I make them often. Heavy on maple syrup, but worth it.

100g ground almonds

1 teasp baking powder

6 tbsp spelt (or other plain) flour

130g creamy tahini

10 tbsp maple syrup

a good pinch of salt

Preheat oven to 180C (fan oven) and line one or two baking trays with baking paper.

Place ground almonds in a bowl, add baking powder, flour and salt, and whisk to remove any lumps.

Add tahini and maple syrup and mix until smooth.

(Optional) place in fridge to chill for 20 minutes (I don’t).

Scoop heaped tablespoons from bowl and form into balls.

Place on baking tray/s , squishing slightly to flatten.

Bake for around 12 minutes or a little more (usually 14, I find) until cooked but still a little soft. They will firm up as they cool.

Store in an airtight container for up to a week - and they are fine for longer than this.

SAINT JAMES, STAGGERWORT & THE WITCHES’ SABBAT

As patron of horses and colts, St James is said to watch over those on overland pilgrimage as they journey to their destination. And here we have a link to one of the wild plants that I’m starting to notice opening its starry golden flowers all over the heath right now. I’ve recently learned that another name for ragwort (Senecio jacobaea) is St James’ Wort and now I can see why, as it really is making its presence felt.

Strangely perhaps, given that St James looks after horses, ragwort is poisonous to horses and cattle alike. Although the animals won’t eat the growing plant, they will happily consume it once it’s dried out, and it often finds its way into hay fodder. There, it causes irreversible cirrhosis of the liver which is usually not noticeable until the damage is done. Sadly, one of the clues that this has happened is the onset of walking difficulties, hence one of ragwort’s other common names, staggerwort.

Folklore has it that ragwort is one of those plants especially favoured by the Fair Folk and that they use it to shelter safely from the rain. This of course would only work when it’s in flower, so it must be a great relief during this wet summer that clusters of the starry blooms are arriving in their full glory. The Hidden Ones are also said to ride on stems of ragwort, skimming the surface of the water as they fly from island to island around the coasts of Albion.

Perhaps better known riders of ragwort are the witches. Many old tales relate that they would mount the stems and, as Nigel Pearson puts it, ‘speed over mountains and crags in their midnight revels and fiendish doings, all at the beck and call of their dark Master’.

Ragwort on the heath at the full moon, 21 July 2024.

As this plant is so devastatingly poisonous to horses, the specific mention of ragwort stems being ridden as a steed is very interesting. It seems like the kind of inversion or subversion that’s very typical of witch lore, much like reciting the Lord’s Prayer backwards or circling a church three times widdershins.

It may be the bane of livestock keepers’ lives and have its Otherworldly or otherwise dark reputation, but ragwort has another side. It is a plant with many useful properties which have always been exploited by humans rather than shunned. It has been used in folk medicine for quinsy, boils, burns, scalds, cuts, coughs, ulcers, inflammations, rheumatoid arthritis and fistulas. These days it is only used externally as some of its constituents are now of doubtful safety, but it’s still used in ointment form for gout, lumbago and sciatica, and a tincture of the flowers is applied externally too.

In common with flax and nettles, a strong rope can be made from the fibres of its tough stem and these have traditionally been used for tying down thatch. The stems were also used in basket making and weaving, and dyes of bronze, green and orange can be extracted from various parts of the plant. I definitely feel inspired myself to see what I can create from faery and witchy ragwort.

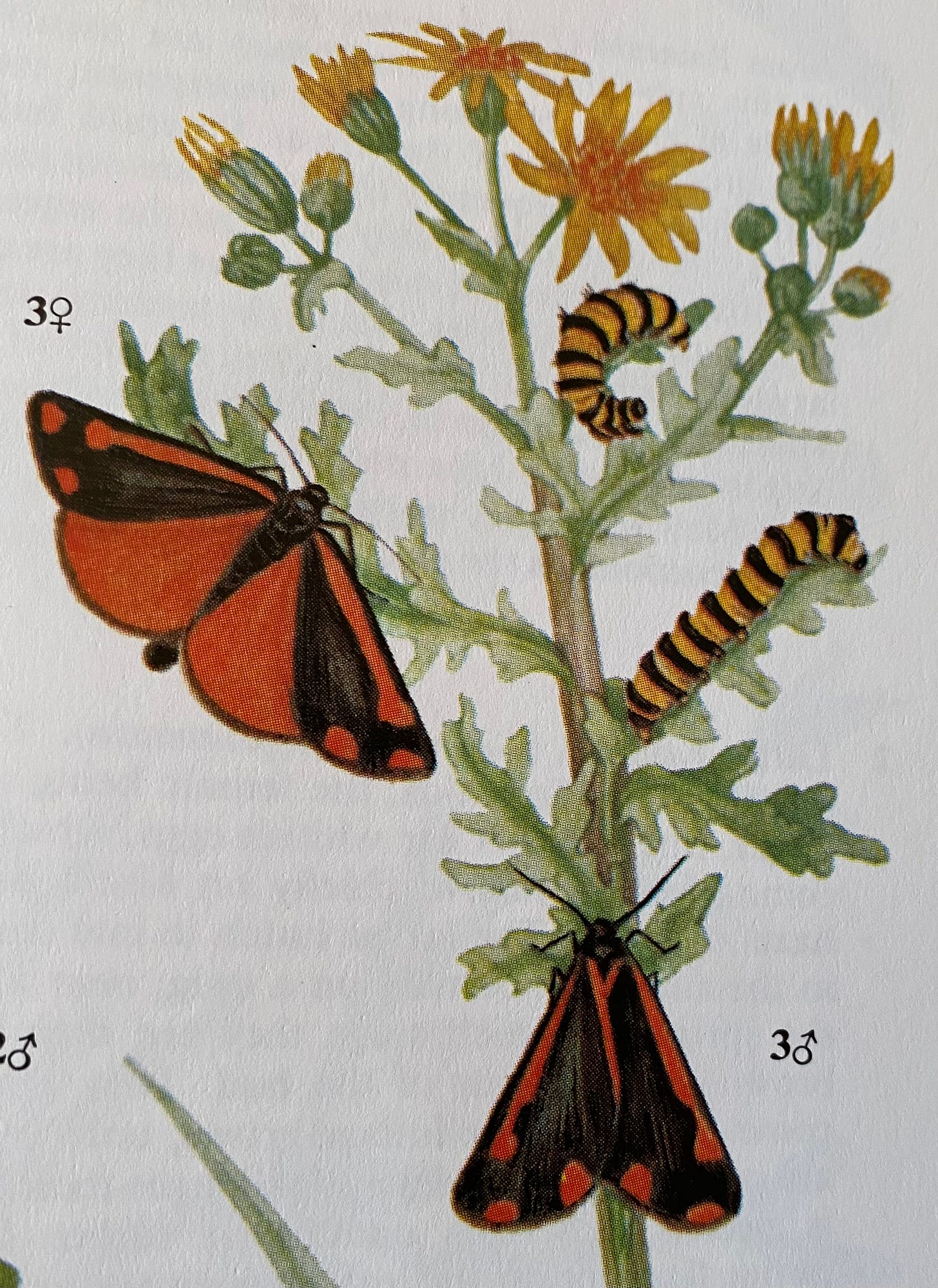

And I just have to mention that ragwort is almost the only foodstuff of the caterpillar of the cinnabar moth. When you see this moth you know it straight away as its colouring is so vividly red and black, which is actually a defence mechanism as predators know it to be bitter and unwholesome and are instantly warned off. The caterpillars themselves are perhaps even more striking with their orange and black stripes, and the sight of them always connects me with a vivid childhood memory.

When I was seven I moved with my family to a big ramshackle Edwardian house in what was then a village close to Norwich. We moved on the date that my parents called Midsummer Day, actually the Midsummer Solstice as it was 21 June. (As an aside, I love that this day was always remembered as the anniversary of our move and we would have special Midsummer Day choc ices for pudding each year on that date in celebration.)

The house and garden were completely magical to a small child. There was a big rectangular lawn that I think must have been a croquet pitch with banks on two sides and slopes downwards on the other two. Broken steps hidden in the undergrowth led up to a tumbledown wooden summer house in one corner.

But on our arrival, it was none of these details that struck my four year old brother or me. It was the enormous field - as it seemed to small children - of waving starry flowers above curly green leaves and thick stems, taller than my brother and certainly up to my own shoulders. We knew, because the first thing we did was to make our way along the whole length of it, my brother soon disappearing from sight. What had once been a lawn was now a single expanse of ragwort as far as our eyes could see, and crawling, arching and sliding over every plant were innumerable orange and black striped caterpillars. It was a sight I had never come close to witnessing before, as the whole of my short life before that had been spent in a modern suburban semi. And as you can imagine, I’ve never forgotten it.

I would like to say that I didn’t try to take some of the caterpillars to school with me, complete with their supply of ragwort leaves, but to be honest my memory becomes a little hazy at this point and I can’t be absolutely sure that I didn’t. These days I am thrilled to be able to watch the activities of just one or two of the surreally-coloured larvae as the ragwort flowers on the heath open their petals to the sun. And of course, I’m transported back to a magical fairyland of a garden: warm, golden and buzzing with summer life.

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

In the 1800s, green clothing and wallpaper was often dyed using Scheele Green, which was discovered by Swedish chemist Carl Scheele and derived from copper arsenite. Unfortunately, the deathly side effect of the beautiful green dye was arsenic poisoning. This most likely contributed to the colour green being perceived as unlucky.

I love your writing as well as the folklore from your mother's book that you so generously shared. Looking forward to the next article!