Willows by the edge of the lake, Alton Water, Suffolk. 6 April 2024.

If ever I saw blessing in the air

I see it now in this still early day

Where lemon-green the vaporous morning drips

Wet sunlight on the powder of my eye.

Blown bubble-film of blue, the sky wraps round

Weeds of warm light whose every root and rod

Splutters with soapy green, and all the world

Sweats with the bead of summer in its bud.

If ever I heard blessing it is there

Where birds in trees that shoals and shadows are

Splash with their hidden wings and drops of sound

Break on my ears their crests of throbbing air.

Pure in the haze the emerald sun dilates,

The lips of sparrows milk the mossy stones,

While white as water by the lake a girl

Swims her green hand among the gathered swans.

Now, as the almond burns its smoking wick,

Dropping small flames to light the candled grass;

Now, as my low blood scales its second chance,

If ever world were blessed, now it is.

Laurie Lee, ‘April Rise’

(Press play for the audio version)

Swan through the willows, Alton Water, 6 April 2024.

Hello, and welcome to this new moon edition of Bracken & Wrack.

Thank you for joining me again for a wander onto the trackways of the season. When I begin these newsletters I never quite know what will end up in them, so it’s all an adventure (albeit a tiny one!)

It’s lovely to be back here with you in the days after the super new moon in Aries, which was also a solar eclipse. I’ve just been reading about this event, which in parts of the USA was a very rare total eclipse of the sun, quite spectacular to witness. Here in Norfolk we were too far east to see anything out of the ordinary, although in Ireland and the western parts of the UK there was a partial or penumbral eclipse when part of the moon’s shadow appeared to take a ‘bite’ out of the setting sun. I would definitely have watched if I wasn’t hundreds of miles away!

Something that caught my eye and struck a huge chord as I look around me at new life bursting forth all around my cottage, was the repeated assertion that this eclipse, coupled with the strength of the new moon and the sign in which it took place, are a very powerful combination. ‘Fiery, driven Aries is eager and ready for fruitful new beginnings’, I read. Even if you take astrology with a pinch of salt it does feel as if everything within and around us is aligned for the bursting forth of unstoppable change and vitality. Just stepping outside you sense how the buds are exploding from their casings as the sap rise and rises.

Fiery gorse blossom on the heath. 5 April 2020.

Once, total solar eclipses are likely to have been regarded fearfully because during the event the light – and therefore Earth’s source of life – is temporarily blotted out. Today we know that solar eclipses only block the sun’s light for a moment and then release a tremendous force. You could say it’s a bit like a dam: when a blockage is removed, the river flows faster than before. So, who knows, by the time you read this edition of Bracken & Wrack in the days after the solar eclipse we may all be feeling a beautiful whoosh of fiery, vibrant light :-)

As you may have realised, yet again I have seen a theme emerge and weave its tendrils in and around this issue of Bracken & Wrack. With dancing flames and sparks that explode and fly in all directions, it’s fire that has come to the fore this time.

In this edition:

Solar Eclipse in Aries

Loki and the Craft of Fire

Poetry by Laurie Lee and Ogden Nash

Deer Tales

Up in Flames: the Crowland Martyrs

Grimkeld’s Wild Garlic Pesto

LOKI AND THE CRAFT OF FIRE

With fire as our guiding force, who better to write about than Loki ?

Now, like many of the topics we touch on here, there is a vast amount I could write about the Northern trickster god. I could easily imagine filling an entire essay, and if I were to write a book entirely devoted to Loki I would not be the first person to do so. If you would like some further reading on the Norse and Anglo Saxon gods, there are lots of options and I hesitate to suggest one above another, but you could try Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology or Kevin Crossley-Holland’s The Penguin Book of Norse Myths for a general overview of Loki’s role in the Northern world. And indeed our own: there is always space for a trickster god. Getting up close and personal, there are works specifically about Loki, like Heart on Fire: a novena for Loki by Galina Krasskova.

Loki makes the world more interesting but less safe. He is the father of monsters, the author of woes, the sly god. - Neil Gaiman, Norse Mythology

Rather than giving yet another overview of this most paradoxical of deities, and given the slant of this edition of Bracken & Wrack, I’m focussing on the fiery aspects of Loki. His (or indeed, her, according to some of the myths) feast day, appropriately enough, is said to be 1 April or April Fools Day. After all, like the god himself, this day holds a double aspect. Traditionally, anyone playing a trick after midday is liable to be taunted with ‘April Fools Day’s past and gone / You’re the fool and I am none’. And strangely enough for a day renowned for silliness and laughter, in past times it was considered ill-omened to begin a new project or enterprise on this day despite it being the start of a new month which might seem to be the perfect time to set out along a fresh path.

It’s true to say that Loki is nothing if not enigmatic and ambiguous. He has been hailed as the embodiment of fire (which is our starting point here) under which aspect he is called Logi, Loge or Logr . This has, however, been hotly debated since the identification with fire is apparently based on a mix-up with the word logi, meaning ‘fire’ in old Norse. This fire-god is held by many scholars to be a completely different entity, because Logi and Loki fight each other in one of the myths making it illogical to believe they are one and the same.

Fire on the beach, Trimingham, Norfolk.

Despite this uncertainty, from traceable and living folk customs of Scandinavia it looks as if Loki actually was linked with the element of fire after all. He has been honoured as a guardian of both hearth and forge fires, and is still given offerings and prayers in this role. In Walking the Tides, Nigel Pearson tells us that through this connection he had a very significant role in Norse religious and sacrificial rites involving fire. Something else Pearson says about Loki also made me sit up and take notice, as Loki is still venerated in some streams of witchcraft today and apparently a Traditional coven in North Norfolk (which can’t be far away from me) holds him as one of their patron deities.

That’s interesting enough, given the Viking and Anglo-Saxon heritage still lying just beneath the surface of the heaths, fields, woods and streams of the land whose tracks I tread. But, as I mentioned in A Trail of Heron Feathers, my maternal ancestry is from deep in the Fenlands where other traces of Loki have persisted as well.

More on them in a moment, but first I want to turn to Nigel Pennick who, in his book Rune Magic, is quite specific in linking Loge and Loki as two aspects of a single energy current:

‘The Northumbrian rune Cweorth represents the climbing, swirling flames of the ritual fire. It describes ritual cleansing by fire, and the sacred hearth. It is the process of transformation by fire. In the case of the funeral pyre, one of the aspects of Cweorth, fire serves to liberate the spirit so that it can be born in a new form. More commonly, Cweorth represents the festival bonfire of celebration and joy.

Magically, Cweorth is used to bring about all kinds of transformation. Its element is fire and its deity is Loki in his aspect as the god of fire, Loge.’

In Pennick’s Northern magical practices, Loge is one of the guardians of the directions, standing at the place of fire in the south.

Well, we can certainly sense the slipperiness of Loki. Like fire itself, he is impossible to pin down. Fire can heal, cleanse and gently warm our bare skin, or destroy and consume all in its path. Fire plays its part in funeral and festival without differentiation - it’s all fire.

Back in the Fenlands, a certain piece of folk magic is mentioned both by Nigel Pearson and Nigel Pennick, although each give the practice a slightly different emphasis.

Pearson relates that, in the East Anglian Fens, Loki was named in a healing charm against the ague or malarial fever which was prevalent in this damp and watery location. Up until the 19th century, he says, to effect the charm a horseshoe had to be nailed up using the left hand, whilst reciting:

Father, Son and Holy Ghost

Nail the Devil to the post

Thrice I smit with Holy Crook

With this mell I thrice do knock

One for God, one for Wod and one for Lok.

(Smit is smite, or hit; a mell is a hammer, Wod is Woden and Lok is Loki - Pearson.)

Nigel Pennick gives a slightly different version containing (it seems) no Christian elements. He says that in traditional nail magic, the hammer used to drive home the nails is an echo of the god Thor’s hammer Mjöllnir, as the sign of the hammer was commonly used in Viking times for consecration and personal protection. Priests made the sign over a wedding couple, it was made over meals and ploughmen used it over the fields.

When you nail up a horseshoe over a door for magical protection, says Pennick, you should recite this rhyme which is in essence identical to the one given by Nigel Pearson:

Thrice I smite with holy crock

With this mell I thrice do knock

One for God

One for Wod

and one for Lok.

Without the references to ‘Father, Son and Holy Ghost’ in the earlier example, Pennick interprets the word ‘God’ as Thor, the god of the hammer, which does make sense as Thor would then be invoked alongside ‘Wod’, Woden and ‘Lok’, Loki.

Now, this is where I start to get goosebumps.

Remember earlier on how Nigel Pearson told us that the horseshoe charm was known to have been used up until the 19th century?

My grandparents Holley and Mabel lived on the High Street of a Fenland village in Huntingdonshire. While my mum was growing up there, a smallholding lay behind the unassuming frontage which jostled with others right against the pavement. But by the time I was old enough to remember our journeys across the Brecks and the Fens to visit Grandma and Grandad’s cottage (a world away, in every sense, from our modern semi in the suburbs of Norwich) most of the land had been sold off and you walked to the back door down a garden path with grass on either side, a small vegetable patch and a black-pitch shed.

My grandparents, Holley and Mabel Ashmore, on their wedding day in 1922.

Of all the things that must have happened during our visits that are now entirely erased from my memory, why do I remember so vividly the incident I am now about to relate to you? I must have been very, very young as my grandfather was still active: I’d guess no more than five years old, so it was during the 1960s. I was at the far end of the garden with him, and he was nailing a horseshoe above the door of his shiplapped, wavy-edged shed.

I’m sure you’ve guessed by now. Grandad recited this very rhyme while knocking in the nails. The part I can hear him saying right now is ‘One for God, one for Wod and one for Lok’. Oh yes, a magical three nails, a Trinity of gods, and this from a Fenland-born Chapel boy.

The horseshoe, the nails, the hammer: these of course are all tools of the trade of a blacksmith who wields and works magically with Loki/Loge’s element of fire.

But another Craft combining fire and hammering is that of the wheelwright. And although I never knew him, Grandad’s own father was a wheelwright. On the other side of the High Street in the same village, in fact. I have heard tales of how the wheel hubs were cast from molten metal, the rims shaped by fire and by hammer and the red-hot metal quenched with water from the River Ouse which ran through the bottom of the garden at ‘Ousedene’, my great-grandparents’ street farm.

So it seems possible, quite possible, that the hammer charm came down in an unbroken line for generations of chapel-going Fen folk, who believed in its efficacy against all harm.

As long, that is, as they continued to ask for the protection of the Old Ones.

I found and rescued this very old horseshoe from my mum’s house while clearing it. Could it have come from my grandparents’ or (more likely) great grandparents’ home in the Fens?

Praise the spells and bless the charms,

I found April in my arms.

April golden, April cloudy,

Gracious, cruel, tender, rowdy;

April soft in flowered languor,

April cold with sudden anger,

Ever changing, ever true --

I love April, I love you.

Ogden Nash, ‘Always Marry an April Girl’

Deer Tales

Red deer herd, just beyond the boundary oaks of Crow Wood.

Deer! On the other side on the stream. A feeling that I was being watched ... and there they were in the distance, a herd of red deer trotting out of the plantation like so many fairy cattle - 4 April 2020.

Happening upon yesterday’s herd of red deer reminded me of the pair of wooden deer (of uncertain species) who reside on my tiny bathroom windowsill. Fittingly, they’re looking out wistfully towards the birch-lined heath. I spotted them in a charity shop in Cromer while still living in a caravan in the front yard. They were the first new occupants of my cottage, seeming to find an easy home here even before I’d settled in myself - 5 April 2020.

Up In Flames

Among the saints’ feast days at this time of year is one that stands out; that of the Crowland Martyrs on 9 April.

I have a great interest in Crowland Abbey near Peterborough as it plays a leading role in the story of the Anglo-Saxon noblewoman turned hermit Pega, who I initially introduced here in ‘St Pega and the Stream’. I’m still planning to focus on Pega’s story in a longer-form piece of writing but that is something to talk more about another time.

Strangely enough, and eerily enough, Crowland’s history has been punctuated by horrific episodes connected with fire. The building of the abbey began in 716, two years after the death of Pega’s brother Guthlac (and in his honour). It housed a magnificent shrine to Guthlac to which pilgrims flocked from far and wide, but in 866 the building was burned down and its community slaughtered by Danish Vikings.

‘What of Abbot Theodore, slain at the altar while praying for the souls of the marauding Danes? What of Turgar, a thirteen-year-old boy who fled with a brother monk as the remains of the abbey fell in flames around him?’ - Edward Storey, The Solitary Landscape

Refounded in the reign of King Edred, it was again destroyed by fire in 1091, when the abbey’s famous library of 700 manuscripts were burnt to cinders. Then about twenty years later it was rebuilt by Abbot Joffrid. In 1170 the greater part of the abbey and church was once more burnt down and once more rebuilt, under Abbot Edward.

Up in flames three times, and three times rising up from the ashes. It is quite a place.

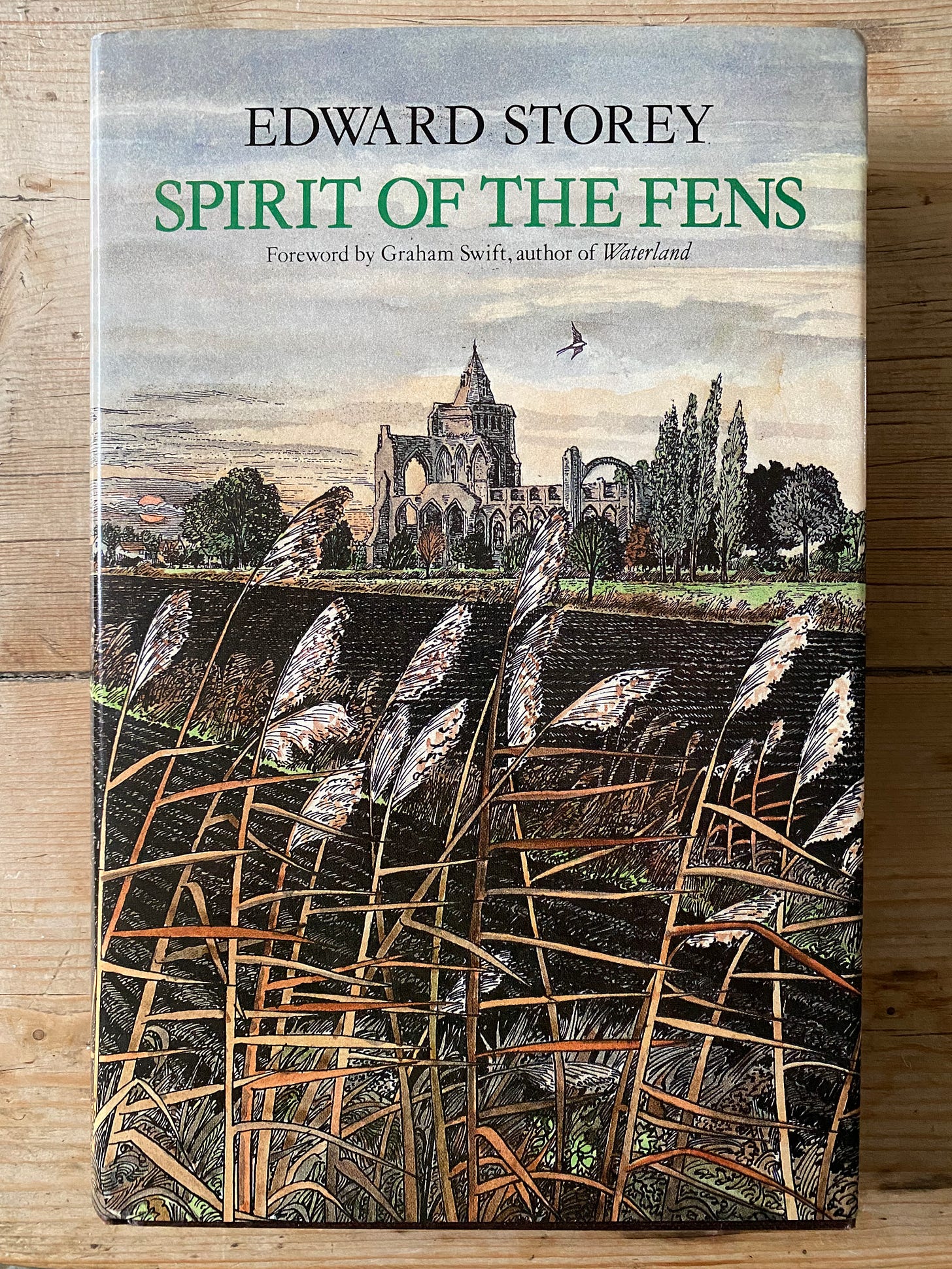

The cover of Edward Storey’s book, depicting Crowland Abbey seen across the fen.

The Crowland Martyrs venerated as saints on 9 April are those Benedictine monks who were slain by the Danes during their invasion of the abbey. Those named are:

Theodore, the abbot. His skull, complete with its hole made by a Viking sword is still kept at the Abbey and he is acknowledged as a saint in his own right.

Askega, the prior

Swethin, the sub-prior

Elfgete

Savinus

Egdred

Agamund

Grimkeld

Ulrick

It feels important to say all of their names, and what fabulous Anglo-Saxon names most of them are.

Their feast day happens to coincide with the time that wild garlic is at its most rampant in the damp grounds that it loves - no doubt forming aromatic carpets in the Fenland area where Crowland lies. The monks with their Benedictine rule of honest labour would certainly have made use of its abundance, just as I myself did when I collected a basketful from beside the Otter Stream to make some wild garlic pesto.

Today I consulted my trusty Culpeper’s Herball to see which astrological body the plant is ascribed to. And given the way that everything in this edition seems to be falling into place, I’m sure you won’t be surprised to hear that the great 17th century herbalist/astrologer gives wild garlic to Mars, the planet of fire and ruler of Aries.

GRIMKELD’S WILD GARLIC PESTO

When Grimkeld went out with his gathering basket to the swathe of wild garlic he had been keeping his eye on, he would not have dreamed that one day I would be making pesto by throwing everything into a Magimix. He would not have called it pesto, of course, and he would have used a pestle and mortar to work his ingredients together. But one thing he would have enjoyed, I’m sure, is the way that a fiery preparation like this would have given extra flavour to the plainly cooked vegetables the the monks were served on fasting days. And its fresh taste speaks of spring celebrations too, and the return of the green.

A big handful of wild garlic

40g hazelnuts, walnuts, pinenuts or almonds, toasted (I used walnuts for mine)

2 heaped tbsp nutritional yeast flakes for a vegan version (otherwise parmesan cheese)

Juice of 1 lemon

Extra virgin olive oil

Salt and pepper

Wash the wild garlic and put it in a food processor (or make the whole thing in a pestle and mortar). Blitz until fairly well broken up.

Add nutritional yeast and mix again, and then add nuts, lemon juice, seasoning and a good glug of olive oil.

Process again and then keep adding olive oil until you reach the consistency you like, whether for drizzling, spreading or adding to soups and pasta. Be warned that the flavour is strong (well, mine was) so you may want to use sparingly and see how you go.

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

Thank you for such wonderful writing! I learned some new things this morning!

Inspirational as always Imogen. Wordsmithery right there x