Willow on the bank of the River Waveney, Homersfield Bridge, 18 October 2024

Hello, and welcome to this deep autumn edition of Bracken & Wrack, a little after the full moon in October if truth be told.

It really does feel as if the season is poised, waiting for something to happen. Harvest-home and Michaelmas have been and gone and Hallowtide with its mists and frosts is not quite here yet. To add to the confusion, the days - and even the evenings - are surprisingly mild for beyond the middle of October.

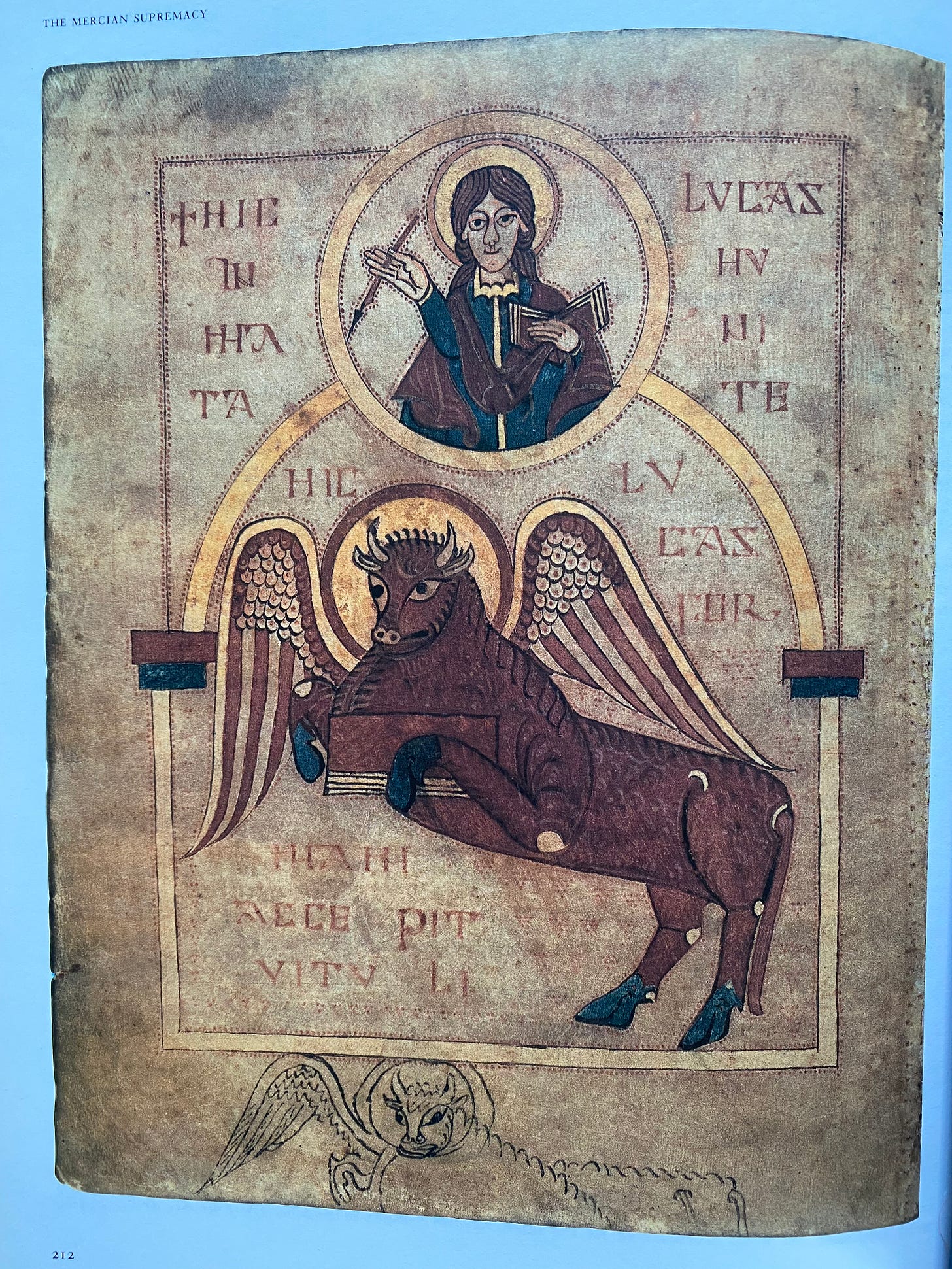

Or maybe not that surprising, when you remember that 18 October is St Luke’s Day, and that year after year I’ve observed the phenomenon of St Luke’s Little Summer, which I wrote about this time last year in A Ripened Sun. True to form, this year the weather forecast for 18 October gave full sunshine all day, and we even managed a quick dip in the sea. There’s lots more about St Luke and his Little Summer in the article linked above so do have a look if you’d like to. I was interested to reflect again that St Luke’s symbol is the bull and that his feast day falls very close to the full moon known as the Hunter’s or Blood Moon. Appropriately, this was traditionally the time when livestock that could not be fed through the winter were killed and butchered. This year the bull and the hunter almost collided as the full moon occurred on 17 October, and what a beautiful Super Moon it was. The third of four consecutive Super Moons it was the largest and brightest of the year, as the moon’s orbit brought it the closest of the four to the earth.

Saint Luke and his winged bull from The Book of Cerne, early ninth century

(Click to hear an audio version of the poem)

My weald of tales, my beech leaves, my bronze,

A world of trees shades the land’s shadow.

Under the tribe’s winter, roots of iron,

Roots of grain; and at the thicket’s heart

A man’s tread, a bird-cry, the glitter

Of a pool rippled with a stone blade,

His last gift. My green eye shuts. Slowly

Drops of light in the night sky falter

My gifts for him: The Hunter, the Plough.

Michael Vince, ‘The Thicket’ (part I), Trees Be Company

Little autumn tree made from dogwood clippings from the garden and some odds and ends found in the bedroom cupboard :-) 16 October 2024

I’m really happy with this simple little seasonal tree (well, simple except for the injury I did myself on the secateurs while cutting the dogwood twigs, ouch). If you’d like to see the moment I made it, it’s in my most recent YouTube video The Autumn Deepens: my October Days. Rather than linking that one here, I thought that instead I would suggest a video that I posted on 15 October two years ago. There are some different seasonal bits and pieces in it that there’s not room to include here, so hopefully it will add a little to the deep autumn feel of this edition.

THE BLOOD OF THE VIKINGS

On 18 October 1016, the Danish king Canute (Cnut) fought King Edmund Ironside and was victorious. By way of remorse for the copious killings, it’s said that Cnut built Ashdon church in Essex over the graves of the English. But as he was still a pagan at that point, he buried his own dead under the enormous barrows close to the boundary between Essex and Cambridgeshire known as the Bartlow Hills.

Originally there were seven of these barrows but now only four are easily visible, of which three stand in a close grouping. If you visit the Bartlow Hills today you will notice one thing before anything else. They are absolutely enormous. No photograph can possibly prepare you for their height in real life, you just have to go there for yourself. Climbing them is definitely not an undertaking for the fainthearted. Or, at least, it’s not too difficult to haul yourself to the top but it’s the slippery descent that takes a bit of nerve.

After the initial shock of their sheer dimensions you might notice an information panel, on which you will read that these are actually Roman burial mounds. You’ll see images of some of the artefacts that have been excavated here, some probably unearthed by unscrupulous Victorian amateur archaeologists. But despite all that points to the contrary, local tradition will insist that the barrows are indeed of Danish origin and it cites powerful evidence that this is the case, as dwarf elder (sambucus ebulus) has always flourished on them.

With stems and leaves that turn red in September, dwarf elder has many folk names connected with blood - and specifically with Viking blood. Danewort, Dane’s Weed, Danesblood, Deadwort and Blood Hilder are just some of them. It often grows in churchyards and likes disturbed soil which may account for its presence around burial mounds and battle fields. It was certainly linked with blood shed by the Danes (rather than Danish blood) by the 15th century when John Rous of Warwick (d. 1491) asserted that wherever villagers were slaughtered by the Vikings, you could see the dwarf elder springing from their blood. But it was in connection with the Bartlow Hills that the abundant Dane’s Blood growing there was first explained as the blood of the Danes, by William Camden in his Britannia of 1607.

Without having any real idea of what awaited us, we followed the footpath behind Bartlow church. Although closed for repairs, the church had been unlocked just for us thanks to a lucky encounter in the churchyard. And it, too, held many stories. Just one of these is that Cromwell’s horses were stabled here during the Civil War, and despite this some beautiful medieval wall paintings survive.

If you visit the barrows, I would love to know how you respond to your first glimpse of them. In my case it was sheer disbelief, mixed with the strange feeling of having shrunk to the size of a caterpillar like Alice in Alice in Wonderland. I looked at my photos, trying to choose one that gives some idea of scale but you really will have to see for yourself, that’s all I can say :-)

On top of one of the barrows, looking across to another, September 2024

As for the finds, the information panel tells us that large wooden chests were found in five of the mounds, with food and drink in exotic vessels, decorated bronze, glass and pottery and other offerings deposited in them. Wonderfully, the chests had been buried with lamps still burning in them. There was even an iron folding chair and the remains of flowers, box leaves, a sponge, incense and liquids including blood, milk and wine mixed with honey. The imagination runs riot.

Sadly, few of these artefacts have survived. Some from earlier excavations still exist, although I don’t know where they are. All the objects from later digs were taken to Easton Lodge, Dunmow, an Elizabethan mansion famous for society gatherings where they, along with everything else, were destroyed by fire in 1847.

Sad, yes, but that’s just another story to add to the layers and layers that have accrued since the Romans, or was it the Danes, laid their dead to rest within the fertile earth here. Now we scramble to the top of two of the mounds and survey the scene from our own tiny, fragile perspective. We don’t notice any dwarf elder, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there, dripping blood and mystery. Two lives to add their own colours - even their sloughed off skin cells - to the tale that unfolds day by day, year upon year.

Bartlow Hills as they were in 1776. Local people were convinced that the dwarf elder, ‘Danewort’, that flourished here was a sign that Viking blood had been spilt at this spot

A TWIST IN THE PATH: Old Shuck & The Pilgrims

The cliff edge meanders adder-like, following the whim of the hungry waves. You never know what might lie around the next bend. A twist in the path takes us back towards the sea and our steady pace comes to a sudden standstill. A man sits astride on the sandy path, his laden bicycle propped at an angle, a near silhouette against the blue sky.

We’ve not come across many other adventurers on this section of the coast path so I’m taken unawares. In any case, the focus required to keep moving while my outrageously heavy back pack cuts into my shoulders means I’ve been slow to notice anything more than a few paces ahead. Following behind as I’ve been, I arrive a moment or two later and can already hear voices rising and falling in conversation.

I lean thankfully on my staff as the man looks up at me. It’s hard to guess his age. Not old, not young, 50s maybe? He has the tanned-leather face and arms of someone who has spent the whole summer out of doors. And the assorted bags and panniers hanging from every part of his bike seem to confirm this.

You lean on your staff too. We really do have the appearance of pilgrims, I note happily. The man is asking about our journey; it’s clear that we’re fellow travellers, albeit making our way in the opposite direction. He tells us that he started out from Hunstanton, slowly making his way southwards to Winterton - a distance of 70 miles - from where he’s in the process of retracing his steps. Surely, I think, he must be pushing his bike rather than riding it. Heavily laden as it is, it’s really serving the purpose of a handcart.

I guess that a small tent is stashed somewhere among the packages but that’s just an assumption as there are, of course, other places to sleep; seaside kiosks, bus shelters and church porches to name but three. Still, there is something in the man’s mien that makes us feel that this isn’t a planned holiday so much as the wandering of someone who is perhaps a bit lost in life. When I ask him how long he’s been on the move he looks uncertain and says ‘About two months, I think. I’ve noticed the change in the season. It’s drawing in and getting colder.’

Now, this is towards the end of September. In fact, this very day happens to be my birthday. The autumn equinox has passed and a shiver runs through me. If, as we suspect, he isn’t journeying purely through choice, he’ll soon find himself facing conditions very different from those balmy July evenings when nothing in the world feels better than a life on the open road.

Despite the unspoken differences in our situations I feel a sense of camaraderie. We too walked from Hunstanton when we set off on our midsummer solstice leg and we’re now heading for Winterton. When the man asks why we’re on this journey you tell him that we seek the stories and songs of the land; our land. We set off this morning from the Upper Sheringham Mermaid and plan to finish this section of our pilgrimage at the Witch’s Leg at East Somerton near Winterton.

At these words, the man positively beams. When we first came across him he was sitting in the dust a little wearily; now he becomes animated. ‘Yes! The stories of the land. There’s a board back there - ‘ he gestures back the way we’ve come ‘about a giant black dog. Old … old …. ‘ He wrinkles his forehead in an effort to recall what he’s read.

‘Shuck’, you say with a grin. ‘Black Shuck is said to come out of Beeston Bump. We’ve just been there ourselves.’

View from the top of Beeston Bump, 25 September 2024

We wish our fellow traveller well and continue on the route that Shuck is reputed to take from the high grassy hill that looms over Sheringham, past Cromer and on to Overstrand, where he roams the streets before leaping into the churchyard and disappearing.

Actually, both Norfolk and Suffolk have reason to claim as their own the gigantic, sometimes headless, phantom hound with glowing red eyes the size of saucers. The first recorded sighting of Old Shuck was in Suffolk in 1577, when he broke into a service at St Mary’s church, Bungay, killing a man and a boy before heading to another Suffolk location, the village of Blythburgh. There, he left scorched claw marks on the inside of the door. These are referred to by local people as ‘the devil’s fingerprints’ and can still be seen to this day.

All down the church in midst of fire, the hellish monster flew

And passing onward to the quire, he many people slew.

Since then, numerous other sightings have been reported throughout Norfolk and Suffolk, and not just by those who have been sampling the wares of the Black Dog Distillery based at Fakenham in Norfolk.

The most chilling aspect of the legend is that a sighting of the Shuck - also, according to Westwood & Simpson in The Lore of the Land, known in various parts of East Anglia ‘Old Scarf’, ‘Skeff’, ‘Old Shocks’, ‘Shocky Dog’, ‘Chuff’, and ‘Owd Rugman’ - has often been said to be ominous either of one’s own death or that of a near relative.

But as we shall see in Part Two next time, it is quite possible that poor old Shuck has wrongly received his shady reputation. Have we misjudged his motives all this time? Find out more in the new moon edition of Bracken & Wrack and make up your own mind …

Meanwhile as Hallowtide approaches, the veil thins, and deliciously scary stories seem highly appropriate, let’s stick with Black Shuck as a terrifying presence. After all, sightings of Shuck have been so frequent in Overstrand that his image appeared in the original village sign and an old section of the coast path, Tower Hill Lane, was renamed ‘Shuck’s Lane’ by local people. Here, it’s said that one terrified witness fled after hearing the sounds of panting, howling and scraping of claws, and on turning back saw the glowing footprints of a hound scorched into the tarmac.

Glowing red hawthorn berries along the lane (not as big as saucers … ) 16 October 2024

OLD SHUCK’S WICKEDLY DARK BROWNIE CAKE

And on that note, here is a recipe that you might like to make for the Hallowtide season. I’ve adapted it from a plant-based Deliciously Ella recipe. It’s a dark dark chocolate brownie cake, almost as black as Shuck himself. It cuts into 10 pieces, and I realised that with a little imagination each wedge resembles the long face of the fearsome hound. If you add a ring of 20 glowing red eyes, when cut each portion will have two of these and can see YOU. If you choose to do this, you might use halved glacé cherries, frozen cherries, raspberries, cranberries or anything else you can dream up (I used raspberries). Press them lightly onto the top of the cake before baking, forming a ring about 2 inches from the outer edge.

200g dark chocolate, roughly chopped

150g self-raising flour

50g ground almonds

3 tbsp raw cacao powder

150g coconut sugar

225ml soya or almond milk (or any other)

75ml olive oil

Pinch of sea salt

20 edible round red decorations, eg berries - see note above

Melt half the chocolate, either in a microwave or in a bowl over simmering water; leave to cool slightly.

Preheat oven to 200C/180C fan/400F and grease an 8 inch cake tin and line the base.

Mix together the flour, ground almonds, cacao powder, coconut sugar and salt.

Pour in the melted chocolate, milk and oil, then mix until smooth.

Fold in most of the remaining chopped chocolate, reserving a handful for the top.

Put into the tin and level, arrange the ‘eyes’ in a circle a little way from the edge and scatter the remaining chocolate pieces in the middle.

Bake for about 30 minutes until the cake is set but still has a little wobble.

Leave to cool completely in the tin before removing and slicing.

A 1930s FENLAND CHILDHOOD:

I’ve been looking at my mum Sylvia Ashmore’s memoir again. Sylvia was determined to record what she remembered about her childhood in the Huntingdon Fens before she died, aged 95, in January 2023. The result is Poultry, Plums and Fen Runners which my brother put together for her, printing out just a few copies for family members. I’m so glad she finally finished the book as it was a huge source of pride to her in her last months. And actually, each time I open my copy I find something that might make a little snippet of interest to include in Bracken & Wrack.

Back in the summer, we looked at the magical craft of the wheelwright and at fenland household superstitions This time I’d thought I’d recount my mum’s memories of day to day life on a small farm during her 1930s childhood. This was the home of my maternal great-grandparents, Frederick and Harriet Barrett, who are quite mysterious to me as I never met them and have never even seen a portrait of them.

In his earlier years my great-grandfather had been employed as farm bailiff on a large farm at Billups Siding, and later he managed to acquire his own farm nearby. Colne Fen Farm was just outside Chatteris on the road to Somersham, and was a mixed farm of arable with some cattle, pigs and poultry. During my mum’s childhood there were cart horses too, for the work of ploughing, harrowing and reaping.

A man was employed specifically to look after the horses, arriving first in the morning to feed and harness them for work and leaving last after feeding and grooming his charges. He was paid a little more than the other farmhands. From this, it’s easy to see how the work of a horseman stood apart from the other farming tasks, and to understand how a whole web of lore, magic and secret initiations grew up around this shadowy fraternity.

In his book, In Field and Fen, Nigel Pennick devotes a whole chapter to the secrets of the horsemen, and they are many. As well as elaborate and terrifying initiation rituals, the possession and use of a magically-acquired toad bone was closely connected with the Horseman’s Guild, as it bestowed the power of control over horses. Although such folk practices were undoubtedly present as an undercurrent in rural Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire during my mum’s childhood, she never mentioned them. That’s not surprising, of course, since they were extremely secret and the members of the fraternity were sworn to silence.

With apologies to vegans (including me), but folklore is folklore - here is Nigel Pennick’s song The Toadman. You’ll see that the Horseman’s Word is specifically mentioned in the description.

I often think about my great-grandmother Harriet (born Harriet Pepper). As a spiritual child of the Iceni tribe I am always looking for blood links with the county of my birth. Apparently (and to my delight) she was a ‘foreigner’ whose family came from Norfolk. Admittedly, I think Harriet’s ancestral homeland was somewhere near Downham Market, which is in the Norfolk Fens quite close to the border with Huntingdonshire/Cambridgeshire. But it still counts, right?

It must have been a very hard life for Harriet, with eight children to care for as well as her own farm work to attend to. Unusually for the time, she had had some education and had been taught to play an American organ (I have no idea what that is!). My grandma, Mabel, was the oldest girl and Harriet taught her to read music and to play some hymns, but couldn’t afford to send her to proper lessons. Harriet also did all the admin for the farm and kept the farm accounts as my great-grandfather could not read or write.

The Barrett daughters - Ethel, Ivy, Mabel and little Annie. Mabel was born on 23 January 1897

Being so far from the town there was no water laid on to the property, so all the rainwater was collected from the roofs. There was no bathroom or flush toilet, and drinking water was brought by water cart from Chatteris and stored in a huge tank at the side of the farmhouse. Paraffin lamps were used to light the indoors, and oil lanterns to go outside after dark. Every day these would have to be filled and the wicks trimmed. Cooking was done on a paraffin stove and water for laundry and bathing heated in a coal-fired copper in the scullery.

Harriet was responsible for the chickens and the milk, and from these came her pin money: any money she could make from them was her own. The eggs went to market or were sold at the door, and the milk was made into butter. The dairy stood next to the kitchen in the farmhouse, and my mum remembered it as a large, airy room with a brick floor and a wide stone shelf along one wall. On this stood large, flat bowls for the milk and a separator which drew off the cream from the fresh milk that was brought in twice a day. When enough cream had accumulated it would go into the butter churn, a large wooden barrel on its side. Then you had to turn a handle until the butter could be heard plopping against the side. Turmeric was added to make it yellow before it was made into half-pounds and pounds using wooden butter-pats. Finally it was marked with a pattern on the top, ready for use in the kitchen or for sale.

Frederick, his sons and hired workers ran the farm between them - cultivating, ploughing, harrowing and seed-sowing in winter and spring, and reaping the corn and harvesting the mangolds and potatoes later in the year. Mum and her older brother, my Uncle Tom, would play around in the stackyard and watch their grandfather feeding the pigs, carrying the buckets suspended from a yoke on his shoulders. By summer the straw stack was low enough to play on, providing they kept away from the huge-bladed knife kept in the cut edge of the stack. They would bounce on top of it and then slide down onto the loose straw at the foot.

At harvest time Sylvia and Tom were allowed to watch as the sheaves brought into the yard by horse and cart were pitchforked onto an elevator and dropped into the threshing machine which was powered by a steam traction engine. The grain was threshed from the straw and collected in sacks, and the straw then built up into stacks in the stackyard. My mum was entranced by this.

Old ways like these are still, amazingly, just about within living memory, but oh how I wish I could ask my great-grandparents about the more esoteric customs and folklore practised by the folk of the Deep Fen.

Frederick with some of his sons and men who worked for him with the first tractor to be used at Colne Fen Farm

A HALLOWEEN LOVE SPELL

Halloween is a time for merrymaking and feasting with friends, and afterwards sitting up late into the night to pursue your own spiritual contemplations, your magical labours, and your communion with the saints and the spirits of those you hold dear who no longer dwell with you in the Vale of Tears. - Claire Nahmad, Earth Magic: a wisewoman’s guide to herbal, astrological and other folk remedies

Our Victorian Yorkshire wise woman gives several Halloween divination methods which isn’t surprising given that All Hallows is an especially liminal time when the membranes between the worlds are at their thinnest. In keeping with the preoccupations of the age in which Claire Nahmad’s maternal grandmother lived, most of the practices are methods of discovering the identity of your true love or husband. You could argue all day about gender roles and expectations, but for now let’s just go with it and pick one of them to try. Obviously, substitute ‘wife’ or ‘partner’ if that’s more appropriate, or just wait and see what you see …

For this spell, you will need a quantity of broad-leaved dock seeds. And as luck would have it, right now is the best time to spot their rusty-brown spires along any roadside verge, often so full of seed that they can no longer stand upright. The wisewoman refers to this plant as butterdock. and a little googling shows that they are the same thing, ‘butterdock’ being an old name dating from when the leaves were used to wrap pats of butter.

If you’d like to have a go at this divination practice, go out and collect dock seeds, keeping them in a pouch or some other safe place until 31 October. Dock is such a common plant of the wayside and wild garden that you might not normally even notice it, but now that you’re looking for it you will see it everywhere. The colour that the spires lend to the season is deep, gorgeous, and unlike any other that I can think of. I don’t know why it’s these particular seeds that are called for; perhaps it is partly that they ARE so present at this time of year.

‘The maid who wishes to work lovespells will have collected the seeds of the butterdock, and have kept them safe in a charm-bag until Halloween, or Nutcracker Night as it used to be known. Other maidens at the party must join her in walking to a secluded spot in the garden or some little further distance, where she will take out the charm-bag and dispense the seeds among her friends, keeping a palmful for herself. Thereafter the maids will disperse, each going to find her own place, apart from the others, to work the spell … every maid will bow to the moon …scatter the seed and murmur this charm:

I sow, I sow!

Then, my own dear,

Come here, come here,

And mow, and mow.

She will shortly begin to make out the spectre of her future husband mowing at a short distance from her as the moonlight plays upon the garden. She must take care not to tremble or swoon, as the spell is then broken, not to be essayed again until the following year.’

If you try this and it works, please do let us all know :-)

Dock seed spires just after sunrise near the Hundred Stream, October 15 2024

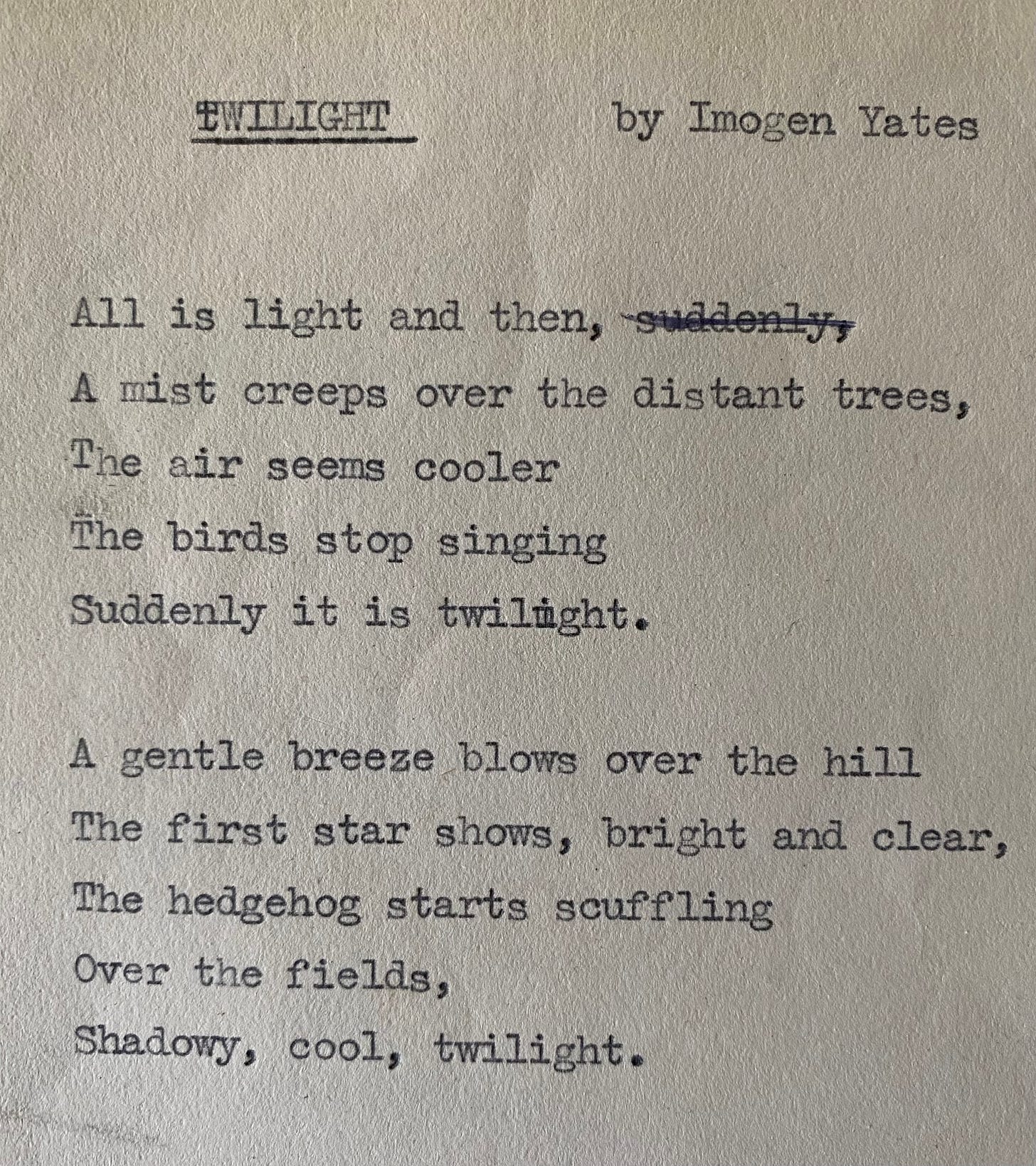

While sorting out my mum’s house I brought back, not only some very old photographs, but lots of my childhood writings and school work that I had no idea she had kept for all these decades. It seems I liked trying to write poetry from an early age. As an English teacher, my dad had a typewriter which I desperately coveted and would borrow as often as I could. A manual one, of course, with a ribbon and with keys that jumped up to tap the paper. I must have typed each word a letter at a time and with one finger, fumbling around the keyboard to find the one I wanted.

I’m around 7 in this photo, I think

Oh and one last thing - I didn’t mean this newsletter to be so late, but one good thing has come out of the delay. This morning I witnessed the moment that the sun rose out of the sea and it was very beautiful, and I’m able to share it now with you.

Sunrise at Walcott, Norfolk, 24 October 2024

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

Such a great read as always. Thank you Imogen. I loved reading the stories of your grandmother’s life. You made the character on the road so real I feel as if I’ve met him myself. I also love Black Shuck. Here in Somerset we have the Gurt Dog, who looks very similar to Shuck but is actually a kind hound who protects children and guides them home if they get lost.

Imogen, it’s so lovely that your mum and Grandmother kept such amazing notes and photos of their families lives. I suspect that it’s quite rare to have so much detail. I love that your mum kept a poem you had typed at such a young age. An excellent poem it is too and definitely worth all the time it must have taken you to write. Thank you for all your wonderful posts, I really enjoy reading them as well as your videos of your garden, you are becoming a very modern chronographer.