May magic: following the tradition of visiting holy wells at May-tide. 4 May 2024.

The month of May was come, when every lusty heart beginneth to blossom, and to bring forth fruit; for like as herbs and trees bring forth fruit and flourish in May, in likewise every lusty heart that is in any manner a lover, springeth and flourisheth in lusty deeds. For it giveth unto all lovers courage, that lusty month of May.

Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte d’Arthur

Hello, and a very warm welcome to this New Moon in Taurus edition of Bracken & Wrack.

As befits the earthy, passionate and beauty-loving Sign of the Bull, this issue can’t help but be filled with the lusty joys of the May, so the theme has really chosen itself with no help at all from me ;-)

In this edition:

The Magical Craft of the Wheelwright

Marking the May

May Revels & Fairy Flutes

A New Moon Walk Along the Lane

A Handful of Woad Seeds

Coffee at the alder carr, 8 May 2024.

A 1930s Fenland Childhood: The Magical Craft of the Wheelwright

In Dissolved in Dew, the last full moon newsletter, I introduced this new series inspired by the contents of ‘Poultry, Plums and Fen Runners’, the memoir my mum Sylvia Yates (1927-2023) wrote and my brother put together into a homespun volume for her. You can read there about why I thought parts of it might be of interest to Bracken & Wrack readers. The whole idea was kickstarted when, in The Emerald Sun, I wrote about a Fenland horseshoe-nailing practice that may just possibly have survived from the time of the pagan Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. I spoke then a little about my great-grandfather’s work as a wheelwright and coach-builder and conjectured that there were perhaps similar magical traditions around the use of fire and water in that trade as there are known to be within the craft of the blacksmith.

Now with Sylvia’s words in front of me rather than just my own memories, I’m going to write a little more about the craft of the wheelwright which, even by the 1930s, was a dying art as motor vehicles began their takeover of the roads, lanes and farm tracks. I feel very lucky to have this first-hand account to share with you.

Thomas Hugh Ashmore, my great-grandfather, was born on 5 February 1869 in Huntingdon, the son of Thomas and Rebecca Ashmore. On his marriage certificate of 1895 he is described as a coach builder living in St Ives. He had been apprenticed in 1886 at the age of 17 to a coach builder in Huntingdon ‘to learn the art of Coach Body and Wheel Making’.

Before the first world war, the wainwright or wagonwright was also the village wheelwright, with the local blacksmith forging the necessary ironwork. My grandfather Holley Ashmore would tell of being late to school when, as a small child, he had to help to take work over to the blacksmith in the early mornings.

Making a wheel was complicated, made only of wood and iron without nails, bolts or glue to hold it together. Its strength depended on the characteristics of different woods - elm for the hub because it did not split, oak for the spokes for strength and ash for the felloes, pronounced fellies (the part of the wheel rim into which the spokes are inserted) because of its toughness. Long seasoning was needed for all the wheel woods.

Once everything was ready and it was time to make the wheel, it would be shaped to slant out at the top and in at the bottom and and was dished like a saucer. The metal rim was a continuous iron hoop made slightly smaller than the circumference of the wheel so that when heated it would expand, and then shrink to fit tightly as it cooled.

As well as farm carts and wagons, wainwrights made governess carts and small carriages, milk floats and tradesmen’s carts. They had to be multi-skilled as wood turner, wheelwright, carpenter, upholsterer and painter. With the painting, great care was needed to get a brushstroke-free finish and to ‘line out’ with a contrasting paint colour along some of the panels and the spokes of the wheels. They also had to be skilled signwriters for their work on the tradesmen’s carts. This again makes me think of magical traditions like those connected with barge and gypsy caravan painting, but who knows?

At my great-grandparent’s home in the deep fenland, all the work was carried out in farm buildings between the garden and the River Ouse. The woodwork, wheels and coach bodies were made in the top shop, a long, light first floor area over the wood store with tools, spokes and felloes hanging on the walls and wood shavings on the floor. One large building was the paint shop where vehicles were finished. All the paints mixed on the spot from basic ingredients, some of which were probably very toxic as they made Holley too ill for him to be apprenticed to his father as a painter and signwriter.

Beyond the old farm buildings a gate led to the River Yard, an area of grass between the buildings and the river. Here, the large round ‘tyring plate’ was used to fit the iron rim to the wheel. The metal rim was heated in a fire to red hot and quickly lowered onto the wheel which was clamped to the iron plate. It was hammered home and quickly drenched in river water before the wood burned. There is no record of accompanying charms or rituals to make the operation go smoothly but I would not be at all surprised if small habitual actions always took place for luck, as there was plenty that could go wrong if the gods were not propitiated.

My mum says that she witnessed this operation only once, when she was no more than seven years old, but never forgot the scene in all her 95 years. By this time there was very little call for Thomas Ashmore’s skills. The top shop still had its benches, tools, shavings and even parts of wheels, but it and the paint shop had been taken over for different jobs. The milk float was still in daily use and Kitty the pony lived in the stable, but times were certainly changing.

The coach making trade was finished as by now the motor vehicle had well and truly taken over, and the village wainwright usually became the village carpenter and coffin maker. Thomas started offering a service to repair and paint motor vehicles, and also took over two plum orchards. The days of fiery magic and drama were over, but I like to think that a little spark from the embers has never quite gone out.

Thomas Ashmore in his plum orchard with Sylvia’s older brother, my Uncle Tom.

The young May moon is beaming, love.

The glow-worm's lamp is gleaming, love.

How sweet to rove,

Through Morna's grove,

When the drowsy world is dreaming, love!

Then awake! - the heavens look bright, my dear,

'Tis never too late for delight, my dear,

And the best of all ways

To lengthen our days

Is to steal a few hours from the night, my dear!

Thomas Moore, ‘The Young May Moon’

Sunrise from the dunes, 5 May 2024.

Marking the May

A few days ago I made a video about May-tide traditions, exploring the idea that we can adapt the underlying themes of growth, fire, passion, flowering and the celebration of beauty to suit wherever we are and whatever resources are open to us. It was also a place to document the wonders of watching the Morris dancing at dawn in the best company on St James’ Hill in Norwich, something I have wanted to experience for decades but had never done until this year of the deepest of magics. For me it marked not only the May but a new beginning full of promise, like a sunrise over the sea.

It’s only short, the most rudimentary of introductions really, but I’ve packed in far more than this newsletter can encompass so I’ve included it here in case you’d like a little flavour of early May in Norfolk.

If you would like the recipe for the May buns I mention in the video - and don’t forget that Old May’s Eve falls on 13 May so there is still a window of opportunity for seasonal feasting - you can find it here, In Apple Blossom. Just scroll down to the end.

May Revels & Fairy Flutes

After showing you my fairy flute in the last edition of Bracken & Wrack I thought that you might also like to see the video from last year’s May Eve and May Day where I took the little flute down to the alder carr to find out what it wanted to play. And my fingers moved of their own accord among the bluebells …

Now the bright morning-star, Day’s harbinger,

Comes dancing from the East, and leads with her

The flowery May, who from her green lap throws

The yellow cowslip and the pale primrose.

Hail, bounteous May, that dost inspire

Mirth, and youth, and warm desire!

Woods and groves are of thy dressing;

Hill and dale doth boast thy blessing.

Thus we salute thee with our early song,

And welcome thee, and wish thee long.

John Milton, ‘Song on a May Morning’

A New Moon Walk Along the Lane

Whatever the time of year, it’s always the scent that hits me first. The unaccustomed warmth of the May sun - or to be more precise the lack of chill easterly wind - has brought the aroma of cow parsley drifting to the fore but the overall impression is of a sweet spiciness with the hawthorn blossom’s intimate perfume a throbbing undercurrent flowing through all the others.

Almost immediately something catches my eye. The very first opened cluster of elderflowers, high up and splayed wide to catch the attention of sun and pollinators. Soon other creamy-white fans will spread open and their strangely alluring fragrance will fill the lane ahead of the deep musk of the wild honeysuckle that drops its namesake nectar, rich and sticky, in the warm summer evenings. That first head of elderflowers is a sign and a gateway.

Forget-me-not constellations spangle the lush hedge bank, crossed through by thrusting lengths of cleavers, rough against the still moist and silky grasses. Rising above them, the cow parsley has a brief moment of perfection and this is it. Stretching on tiptoe, the last flowers still unfolding into the frothing bridal mass with no taint around the edges.

Oh, another first: the curling tendrils and lyre-like leafy stems of the vetch. You need to hold your eye close to drink in the full beauty of its purple blooms like tiny sweet peas. One day soon, someone will probably come along with a strimmer so best grab your fill while you can.

At the wooded edge of the heath there’s yet another first. A single ox-eye daisy taking a recce before its companions open their own golden eyes to the dancing days of May. Behind them, I notice how much taller the foxgloves have grown, their stems already topped with blunt heads that will soon explode into streams of purple-pink and milky white bells. It’s going to be a good year for them. Above the gathered spires, young sycamore leaves stretch green and sap-filled, their sprays of knobbly flowers just on the cusp of transforming into miniature winged keys, playthings for the smallest of the Fair Folk.

Down in the alder carr along the edge of the stream, the bluebells take your breath away. Over the wire and you see how the leaves and stems are collapsing a little now from the sheer exuberance of their juices but the sight and scent are something to hold onto deep inside. Butterflies flit from bell to bell, drinking deeply. Peacocks, and those white butterflies with black tipped wings that are always here. They love this place, as I do.

The light reflected in the marshy waters is green now, rippling with young leaves and promise. Yesterday I watched a nuthatch here, flickering up and down a broken-off alder stump over and over again, eager for its rich pickings. A family of mallards had quacked quietly past; a pair with four tiny fluffy ducklings in tow. And a coal tit had held me in its beady eye while a jay flashed pink black and white through the birches.

Today it seems to be me and the butterflies. And luckily I have remembered to bring my flask and cafetière and one of the last of the May buns so I clamber onto a huge horizontal alder trunk, ridged and rough with dried moss and alder cones. I sit for a while there, sipping coffee and basking in what feels like another first this year - real warmth on my face.

Heading back along the lane I see with a start that the dandelion’s gold has been replaced - seemingly overnight and with a click of the fingers - by a sea of gossamer clocks. Time is ticking, but time is circling too, as time does. My next walk will be different, even if it’s as soon as tomorrow. 8 May 2024

A Handful of Woad Seeds

Woad in flower in front of the Temple of Taranis, Eceni Wells, Norfolk.

A handful of woad seeds reminded me of this place. More than a decade ago, an extraordinary pair of historical re-enactors from Northampton created ‘Eceni Wells’ - a vision of an Iron Age village - on The Midden at Wells-next-the-Sea in Norfolk. The magic that hovered around this place was fleeting, but magical it was while it lasted. With the help of a handful of friends, Steve and Jo raised the buildings from whatever recycled materials they could lay their hands on, and created a dream of what an Iceni (some say Eceni) tribal settlement might have looked like. Well, if the Iron Age inhabitants had been given a job lot of old fence slats to make shingled roofs for their houses and decided that rectangular buildings would be far more commodious than the round ones that everyone else seemed content to settle for.

Steve had initially made contact for archaeological advice - which was not usually heeded it it has to be said :-) This made my archaeologist/prehistorian husband a bit jumpy but I just loved the wholehearted way the couple dived into their project in such a resourceful way, making the most of what they had and going for the spirit of the thing.

During the time when they were building, digging the sacred spring, weaving wattle fences, finding rare-breed sheep, dyeing with woad and madder, spinning wool on a drop spindle, grinding pigments, growing herbs and myriad other tasks connected with their dream, Steve and Jo lived in a static caravan on site. This I visited a couple of times for an evening of scrambled eggs on toast and Lambrini-fuelled conversation. I don’t know whether Lambrini is still available, but it was a weak Babycham type of drink which they bought in huge bottles and consumed like lemonade. I can honestly say that up until that time I had never laughed so much in my life, in fact you would laugh until you were gasping for air as Steve was the funniest raconteur imaginable.

The houses and temple went up amazingly quickly. To step inside each of them was to enter another world filled with the scents of woodsmoke, mineral pigments, herbs and animal pelts. These simple buildings truly felt like living homes: Jo had made up beds in them all, and not only were their friends invited to stay over after nights of feasting and drinking (I never did this!) but the couple themselves slept cosily under wolf skins in each house in turn. These they had somehow acquired from Poland where wolves still roam and sadly, I’m afraid to say, are shot.

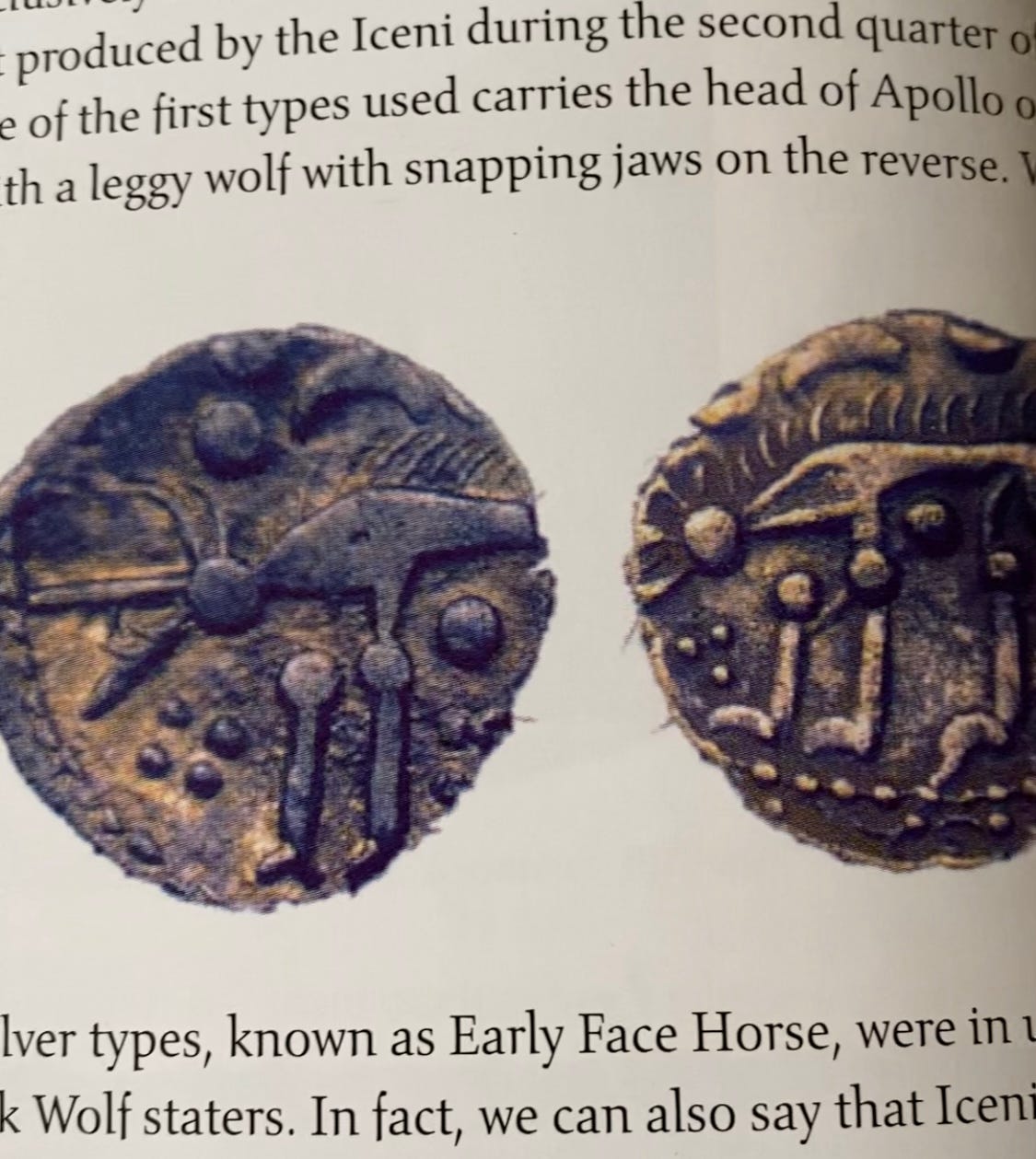

Wolves would also have been very present in Iron Age Norfolk. I wonder whether these powerful and magical creatures may have been held sacred here and not killed, as the Iceni were famously the only Celtic tribe to feature the long-legged wolf on their coins?

Narrow decorative friezes ran around all the interior walls, delicately hand-painted by Jo using natural pigments ground from minerals. She had managed to make a red and a white from the stunning cliffs at Hunstanton and there was also a blue which I imagine was woad, and charcoal or tar black. The designs were all inspired by motifs found on Iceni coinage including the back-to-back crescent moons and triple pellets that are so typical of our local Iron Age tribe.

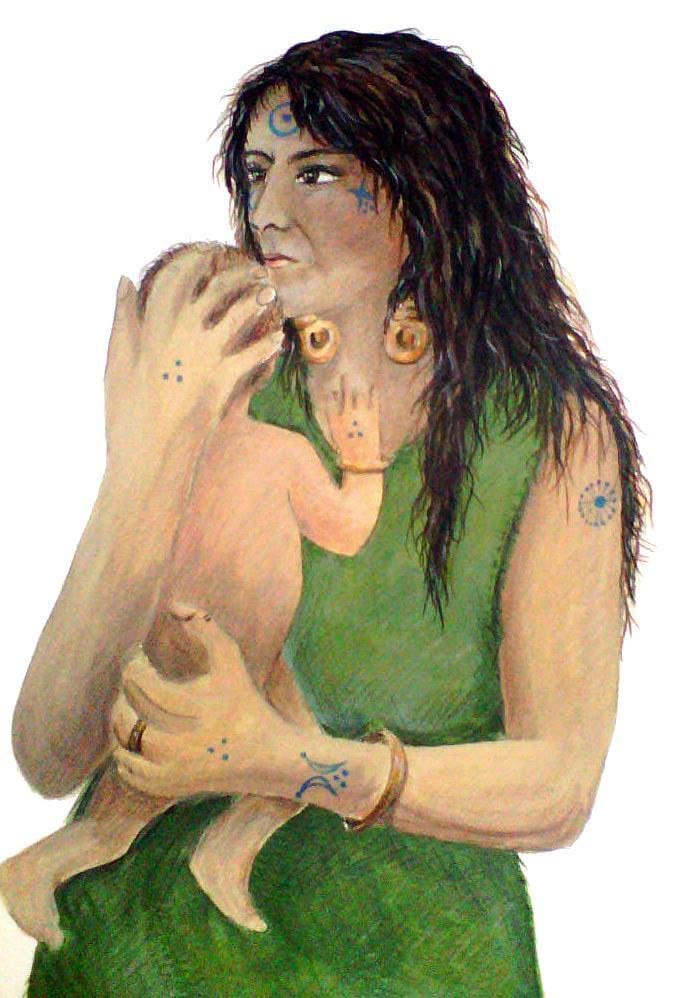

A speculative illustration by Norwich artist Julie Curl, showing how Iceni tribal motifs might have been employed as woad tattoos. I love the baby’s tiny triple pellet on the back of the hand.

My favourite area of all was the temple to the Celtic thunder god Taranis who was the settlement's patron. Inside was oxblood red and was all flickering firelight, playing across the objects on the altar. A brazier was kept heaped with coals so there was a throbbing warmth even in summer, and the branches of bay and other herbs laid across the top smouldered continuously, sending up a sweet smoke whose scent I have never forgotten. The rich paint made the interior dark and mysterious as well as warm, but through the gloom and smoke the glint of metal heaped up on the altar revealed the tribe’s many offerings to Taranis looted, as Steve told me, from the Romans.

On one level it was just an imaginative reconstruction. But inexplicably, the atmosphere was utterly electric, throbbing with presence. I have never known anything quite like it. Rich red sunwheels - sigils of Taranis - decorated the outside of the temple and drew drew the eye powerfully.

I was there on May Day that year, when the temple doorway was flanked by beds of tall, swaying woad plants shining with their own gold in the spring sunlight. Later in the year they would be heavy with umbels of elongated blue-black seeds. In front of the doorway, a statue of the tribe's patron guarded the tribal horn and was decorated with woad flowers for May Day, a simple garland laid before him. His likeness was based on a known carving of a Celtic deity, maybe Lugh. The stone bowl at his feet was always brimming with fresh water.

The sacred spring was another place with a special magic. How was it possible for it to feel so numinous when you knew it had been dug out only a few weeks beforehand and an electric pump installed to make the waters flow? Steve and Jo had commissioned a stone carving of a goddess head to sit above the spring, representing the spirit of the well whose feast day was May Day. Of course she wore a fresh garland of wild flowers in offering. To my surprise I found myself approaching quietly and reverently.

During a later visit Jo invited me to try on one of the headdresses that she had designed and embroidered for her band of Eceni Dancers. The women went barefoot and wore deep pink and blue garments dyed in madder and woad, as they practised slow ritual dances to the beat of a drum. In the open air with the scent and crackle of wood smoke, the effect was hypnotic. Jo had adapted the designs from Iron Age artefacts. She envisaged these bands as also denoting a woman's status within the tribe by means of different coloured yarns bound around the wool streamers that framed each dancer’s face.

I would have loved to join Jo’s tribe of Eceni Dancers but that will have to remain one of those unrealised dreams we probably all have lurking somewhere. Not only did I really live a little too far away but not long after that, trouble ensued at The Midden. I think it was triggered by an argument but the upshot was that the very insecure tenure was taken away and everything had to be dismantled and removed as if it had never been there. The rare breed sheep were moved on to pastures new. I imagine the wood and painted render being piled onto huge bonfires. No trace was left and today it’s just a recycling centre like any other.

Well, I say like any other. But I have grown woad myself and I know that once you have this plant in your garden it will always be present, seeding itself around and about without a care in the world. So I wouldn’t be at all surprised if that mundane recycling centre is actually quite an unusual one. I imagine the heaped treasure-offerings from Taranis’ altar still there after all, transmuted into treasure of a different kind. If you took a carload of rubbish through its gates in May, would you find yourself surrounded by swaying Iceni gold, still standing tall and free?

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

Do you live near where your great grandparents were?

Your great-grandfather’s tale is very interesting. Have you any thoughts regarding publishing your mum’s memoirs as a book? My father’s side were all Wiltshire farmers and there were always old farm implements around the farms, used when my dad was a boy. He explained what they were used for. Uncle used two shire horses to pull the plough and carts right up until the late 50’s. The farrier used to visit and make any necessary repairs on the spot. My great uncle still milked his cows by hand even though his son had bought expensive milking equipment. Uncle said his cows didn’t like it. I loved getting the cows in.

In a way, the painting of wagons continues: I visited a truck show with my son and saw many beautifully painted units all gleaming paint and chrome, modern, yes, but the same pride was there. A few older hauliers still use the old fashioned lettering and detailing in green and yellow paint.