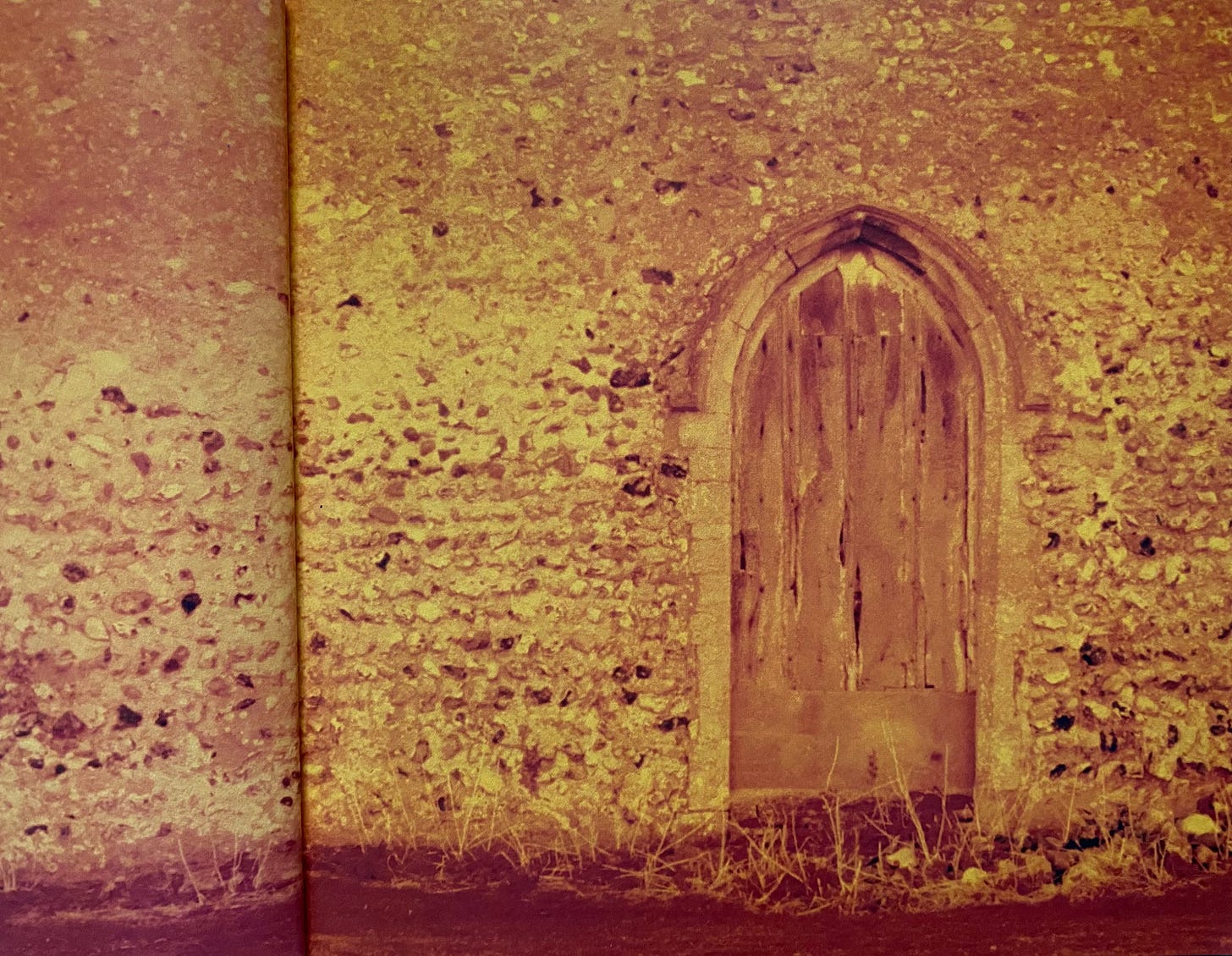

North doorway, Welbourne, Norfolk. Infrared photography.

Someone has mown

a grassy path. It beckons

behind the tower

where slicks of close-packed nettles

press hard against flint.

Shall I run my palm

over their tips?

Now the green path

drops its guard, turns to wild

as if by a click of the fingers.

Playing my game I look away

but resist for

barely a moment.

That smooth stone scar

held at bay by swaying

nettle armies

comes to rest, head on,

as a door.

Green pulses through traces

of worn reddish pigment.

Each rusty nail has a halo

or a shadow.

No lock, no handle

no visible means of

entry or exit.

Shivering, a teased out thread

of spider-silk

seals wood to stone surround.

I’ll just wait here for the devil

to snap it.

Imogen Ashwin, ‘The Devil’s Door’

North doorway, Wilby church, Norfolk, Infrared photography (low res reproduction)

Hello, and welcome to ‘between the moons’. It’s lovely to have your company.

This week marks a whole year since Bracken & Wrack included the option of paid subscriptions to help to support my work. So there has been a whole year of extra content, usually essays on a single topic, which I send to subscribers twice a month between the free new and full moon newsletters.

To celebrate, I thought I would simply send this little piece out to everyone, just for once. I hope you will enjoy it.

It all began as a simple thought that flashed into my mind. All too soon it had turned into an obsession that had me poring over the map for more and more places where I might catch the old horned one himself…

But let’s begin at the beginning.

Reluctant to give up art school life after doing really well in my BA, I had started studying for an MA in Fine Art at Norwich University of the Arts (then called Norwich School of Art and Design). For my degree I had found myself working in video, photography, print and installation (all media I am still drawn to over 20 years later) and in particular I loved the old fashioned processes involved in film photography.

Usually I would bump into the same couple of mature students (who both became friends) in the darkrooms which were otherwise almost empty of humans, although somehow full of potential, pulsing with a gentle expectancy. Ben, the photography technician who spent his days in the half-light, seemed to have a very quiet life. Most of the younger students who liked photography were excitedly exploring the new digital media which were still in their infancy at that time. He welcomed our presence and would go out of his way to find us whatever we needed, glad to know that the magical artes practised in his domain were still in passionate and interested hands. In the warm dark rooms where your eyes needed to adjust to even see whether anyone else was around, our presence became like a secret club of alchemists, turning paper, light, water and mixtures of substances into visual charms that sprang to life as we watched anxiously to see the results of our experiments.

The full time MA in fine art ran not for a normal academic year of September to July, but for an actual year from September to September with our final exhibition being held during the last week or two of the course. Going into college every weekday during that time was an amazing privilege and offered plenty of opportunity for ideas to develop, change and transform into other strands and avenues to follow. Like most of my fellow MA students, the work in my final show was very different from the projects I had been immersed in six months previously, although you could say that my preoccupation with the rational/irrational and human interaction with liminal places in the land always stayed the same at their core.

Quite early on, an issue arose. Even though the MA Show and final marking for the course were to take place in September, the exhibition catalogue had to be produced far earlier, in the February in fact. At that point I hadn’t had any of the ideas that I took through to my exhibition space that September. So, my catalogue submission could only reflect what I was working with (and obsessed by) at that time.

And all of this, to lead us to the Devil’s Door.

Some time previously I had bought a second hand film camera and had absolutely loved taking black and white photos and then developing them into contact strips, working with the images under a magnifier in the darkroom and finally printing them out in the huge machine that stood in the middle of the biggest photography room. You would put in a piece of white paper and as if by magic out would come a test strip or a photograph. Well as far as I was concerned it WAS magic.

But black and white film was not the only kind I had my eye on. There was a sort of duotone film for one thing, that I ended up using later on. But somehow I had heard of infrared film that picked up colour according to the degree of heat that any given object gave out.

And that got my mind racing.

For all my adult life I have been fascinated by one aspect or another of the many medieval churches we are lucky enough to have here in Norfolk. These interests, I admit, have bordered on obsessions and at various times I have felt compelled to find as many Norman doorways, or Norman fonts, or Green Men, or painted rood screen images of a particular saint, as I could reasonably get to from my home.

Now all this talk of heat-seeking film led me to one thought. While the south door of churches is nearly always the one that has seen the passage of footsteps over the centuries, the north door is usually hidden away in the shadows out of sight. It is on the north side that you may find a strange beast or green man eyeing you, and there are few gravestones as it would be deemed far preferable to be buried as close as possible to the sunlit and well-favoured pathway into the church where your name might be read and your status remembered. Indeed, the north side was often reserved for those who were allowed burial in the churchyard, but only just. Perhaps their life had had some kind of cloud over it or their reputation remained in question even beyond their death.

At Houghton-on-the-Hill in Norfolk, for example, during renovations on the north side of the church nave, it was discovered that in medieval times a woman had been buried face down and her body covered in stones. What her story may have been we can only begin to imagine.

Today most of these doorways are unused. Rotting wooden doors may be bolted shut or quite often the stone outline will still be present but the interior has been filled in with flint and rubble or even render. The wild plants that frequently straggle between the door and its stone threshold are testament to its lonely watch at the northern quarter.

Blocked north doorway, Oxwick church, Norfolk.

Now, as far as I am aware there is a rational reason why pre-Reformation churches were built with both a south and a north doorway. The liturgical year was liberally endowed with feasts, festivals and processions, and these last would have their traditional snaking routes taking the participants in, out and around the church building. These paths would enter at the south door and take in the north door as well as the west door if there was one. West doors are fairly uncommon though, so without an exit point in the north there would be no other way out except for the priests’ door which would not be accessible to the laity.

But the liminal qualities of the north door gave rise to a widely-held belief that this door belonged to the christian devil himself. When parishioners entered the light-filled south porch they would cross themselves with holy water and murmur a blessing that would send the devil packing. How should he escape from the church but through his own door - the Devil’s Door?

The devil as imagined in the medieval mind blazed with the fires of hell and carried a pitchfork, the better to push evildoers into the flames. So, I reasoned, if I was going to catch the devil emerging from his door I would have the best chance of doing so with my heat-seeking infrared film. One click of the shutter at the right moment was all it would take.

Well, that was enough. This was specialist film and I would have to have transparencies made rather than doing my own developing but once the idea had taken hold I was soon poring over maps in customary fashion. The exciting thing here was that there were so many churches where either I had never gone around the back, or perhaps I had but because I was set on seeing some other enchantment like interlaced beasts on a Norman font, I had completely forgotten what that doorway might have looked like.

And this is how the ‘game’ began. I would walk slowly around the tower (and you will always find the tower on the west), not letting myself look at the doorway itself. First I would become aware that this particular church actually still had a doorway, as occasionally they have completely disappeared if the wall has been rebuilt. Usually the first clue is the ‘smooth stone scar’ of the poem. Then I would gradually creep around, camera in hand until I was face onto the doorway, and …. click!

I have to come clean and confess that I never did actually capture the devil on camera - although on the north side of one church I discovered a Green Man mask that someone must have hung there as part of a different story.

But you have to agree it was worth a try.

North doorway, Rockland All Saints, Norfolk.

Until next time at the full moon.

With love, Imogen x

Oh yes! The north door is so mysterious and somehow maintains the earlier beliefs that remain beneath consciousness. It enables us to interface with the deep ancestral. side

This is fascinating! I did not know of this folklore of churches, as we don’t have medieval churches in the U.S. (nor am I a churchgoer). I do love folklore and folkways however, and your project makes me smile. Maybe no devil is disappointing, bit of a relief on the other hand. 🙂