Towards the autumn equinox: the sun rises almost due east at the beginning of a beautiful day. Filby, Norfolk, 14 September 2024.

Hello friends, and welcome to this Full Moon in Pisces edition of Bracken & Wrack. And not just any full moon, special as that is in its own right. This is a super moon - meaning that the full moon’s orbit brings it closer to earth than usual so it will appear extra big and bright. It’s also this year’s Harvest Moon which is traditionally the full moon closest to the autumn equinox whether it falls in September or in early October.

More than that, it’s a lunar eclipse and although the actual event will have passed by the time you read this, astrology holds that its effects will continue to be deeply felt. Lunar eclipses happen when the earth is between the sun and the moon, but this one is a partial eclipse, meaning that the three planetary bodies are not fully aligned. While the moon will pass through the earth’s shadow, it won’t take on the dramatic red hues of a total eclipse. Still, it’s a good time astrologically speaking to ready ourselves for positive change in our lives, particularly in the areas of closure, healing and fulfilment of dreams.

Then, of course, we have the autumn equinox itself. This year it falls on Sunday 22 September and many will find this a poignant moment as day and night lie poised in balance before tipping over into the dark half of the year. I’ve read that the weather, and accordingly our emotions, are especially changeable and stormy around the equinox although I don’t know whether there is any actual evidence of this.

I have noticed dramatic skies over the sea over the past few days, though. One thing that’s certain is that, as usual, we will have extra high spring tides in the couple of days after the full moon closest to the equinox. Here, these are really exciting as the high waves crash into and over the sea wall right onto the pavement and even into the road that runs parallel to the shoreline. I can’t wait to go and feel the salt spray on my face - maybe from a safe distance though!

Changeable early morning skies, Walcott, 17 September 2024

Looking back over my writings from Septembers past, I see that I witnessed dramatic skies exactly three years ago. On 17 September 2021 I wrote:

‘Now and again, I climb the hill past the inn and onto the cliff top with my flask and cafetière, and it’s such a magical place to be that I’m content to sit and gaze without going down onto the beach at all.

After all, a kestrel may hover low over the grassy cliff, or a cormorant far below on the groyne suddenly spread its wings against the lowering sun, black against the sea’s azure sparkle. Not to mention the possibility of a smooth grey seal head suddenly popping out of the water. And who would want to miss that?

Cafetière drained, as often as not I’m grateful and content. I’ll turn and head for home without feeling the need to walk the length of the crumbling cliff-path and down the slipway to the sandy bay under the watchful eye of the lighthouse.

But on this particular evening, I did. On the clifftop all had been golden late afternoon sunshine, but as I meandered along the sand, alert for belemnites and carnelians and following the curve of the shoreline, the storm clouds began to roll in.

And then, earlier than I had realised would happen - or maybe it had somehow got late - I looked up and the sun had started to set. And there before me was the lighthouse, rimmed in rose-gold.’

Still on the theme of autumn, I’ve just discovered something that may interest you if you, like me, are fascinated by both words and colour. Anglo-Saxon poetry often refers to winter, usually highlighting the bitter hardships and challenges of the season in its use of metaphor. The season between harvest and frost that we think of as autumn gets far fewer mentions, but in the poems we do have that speak of the time of leaf-fall, one word that crops up more than once is the Old English verb fealewian. In Middle English this becomes fallowen from which it’s an easy leap to glean its meaning ‘to turn fallow’.

But this is where the surprise happens, as if you were Anglo-Saxon you would know the word ‘fallow’ as the name of a colour between red and brownish yellow. If you’ve ever wondered how the fallow deer acquired its name, the answer lies here. Old English colour names do not map easily on to modern ideas of colour, illustrated rather wonderfully by the fact that fallow - fealo - is not only the shade of autumn leaves but also of wooden shields and turbulent winter waves.

Birch leaves are some of the first to turn fallow here on the heath, 15 September 2021

One of the very first magical books I owned nearly 30 years ago was Earth Magic: a wisewoman’s guide to herbal, astrological and other folk remedies by Claire Nahmad. Among much useful and interesting lore, it contains words and phrases of great beauty, rather antique in nature as you might expect from the teachings of a Victorian Yorkshire wisewoman. On glancing at the contents page, I was completely smitten by the evocative sub-headings; phrases to characterise or sum up each month . I don’t know whether the fact that my birthday falls in September had anything to do with it, but probably my very favourite is The Nut-Brown Maiden. I know that deep down I have always aspired to be her, the September girl, free and wild. When I’m not being Arthur Hughes’ lily-white Ophelia, that is.

In this edition of Bracken & Wrack:

Slipped Through From Another World: barn owl magic

Barefoot: a poem

Hollaing Largesse: fundraising for the feast

Layers: oyster observations

Seasonal photography

SLIPPED THROUGH FROM ANOTHER WORLD

I watch them for a long while,

the pair rising and courting the field

in daylight, the strange geometry

of their faces funnelling the air,

and everything – their whiteness,

their sense of having slipped

through from another world,

their focus on the hunt –

in the end it all comes down

to their silence –

the way each feather disperses

the air, how each wavers –

and I wonder what omen it is

to see two barn owls hunting

in mid-morning, so quietly

secretive, for surely

there is something in the slow

spread of the wing, the moment

of inverted flight, the living thing

pulled from the earth and lifted.

Seán Hewitt, ‘Barn Owls in Suffolk’, Tongues of Fire

One day, or perhaps at night during a wild winter storm, in the graveyard of the medieval church at Stokesby, an enormous oak had creaked its last and crashed to the earth. Its impact of its fall was viscerally clear, as flint rubble still lay around where it had demolished part of the old churchyard wall. This I took in in an instant, but a moment later I noticed the very beautiful way the sorrow of its loss had been addressed. The oak’s huge trunk had been sawn straight across, and, in one piece, out of the heart of the tree a barn owl had been carved, shaped, coaxed into life.

HOLLAING LARGESSE

Passing stubble field after stubble field along the lanes, many of them already muck-spread and with their golden bales safely stored in great cathedrals of straw, you would be forgiven for thinking that harvest time is over for another year.

It’s true that there are no more upstanding wheat fields - although the many acres of sugar beet won’t be lifted for a few weeks yet - but still there are links to the harvest season everywhere I look in my rural corner of Norfolk. For one thing, pinned to every supermarket notice board I spot at least one flyer for a church harvest festival or harvest supper. These always seem to be timed for September or even early October, and I’m sure that school harvest festivals always took place in September too. Well, they must have, as we wouldn’t have gone back after the summer holidays until early September and time had to be allowed for us to practice the favourite old harvest hymns like ‘We Plough The Fields And Scatter’ or ‘Come Ye Thankful People Come’, not to mention earmarking the biggest marrow or fattest onions (which somehow in those days, everyone had) to heap onto the school stage in a glorious riot of colour and welter of earthy scents.

So why this mismatch between the actual corn harvest, which is often over in just a few intensive days in July or early August, and the feasts and festivals which traditionally celebrate this achievement with huge sheaf-shaped loaves and plenty of barley-laced ale?

Part of the answer lies in the modern grain varieties that mature faster, and the advances in farm machinery and even the powerful floodlights that allow the low rumble and beep beep beep of the combine harvesters to be heard throughout the night during the most intensive segments of the work. Then as now, in times past the timing of harvest was entirely dependent on the weather but the difference is that went on for roughly an entire month. So, timing the celebrations for around Michaelmas at the end of September made perfect sense.

As Peter Tolhurst tells us in This Hollow Land: Aspects of Norfolk Folklore, everything that happened during the harvest period was conducted according to a set of time-honoured traditions which we know about through written sources like the poem ‘The Horkey’ [an East Anglian dialect word for harvest feast] written in 1802 by Robert Bloomfield from Honington near Thetford, just over the border in Suffolk.

Harvest was the only time, Peter explains, when farm labourers were in a strong bargaining position. They would elect one of their number as Lord of the Harvest, whose task it was to negotiate with the farmer a good rate of pay with generous food and drink rations. During the harvesting month the men could earn double their normal daily rate. There would be a ‘frolic’ to mark the beginning of the contract period and then the reapers would be led into the field by the Lord and Lady of the Harvest. The Lord it was who then called the breaks - elevenses and fourses - and set the pace.

The reapers had the right to claim largesse in the form of a fine, usually a shilling (which was a sizeable sum) that was put in the kitty towards the harvest supper. This ancient custom was known as ‘Hollaing Largesse’ and it was enacted whenever a stranger was foolhardy enough to wander into the field or pass by in the lane while the harvest was in full swing.

‘… the reapers would stop work, gather in a ring and join hands, one man standing in the centre, or just outside the circle, blowing a horn and shouting three times: ‘Holla Lar! Holla Lar! Holla Lar! - Jees!’ Those in the circle, with heads bent, then called out ‘o-o-o’ on a low note before throwing back their heads and changing their chant to ‘ah-ah-ah’, prolonging it until they were out of breath’ - Enid Porter, writing on folklore in the Fens in 1974

Well, I can’t tell you how fascinating I find this. The ritual aspect feels primal and full of magical intent. Non-verbal chanting and holding of a sound reminds me of the runic seed-sounds or galdr that were used magically by our Anglo-Saxon and Viking ancestors, and then there’s the ritual use of a circle and the repetition of the number three.

Even when mechanical reapers and threshing machines put paid to the enactment of the custom in the fields, it continued to be performed outside large houses in the village or in front of tradesmen who had called to do business with the farmer. That Hollaing Largesse has ancient origins is beyond doubt as it’s referenced by the Suffolk agriculturalist Thomas Tusser in his Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry of 1557.

When the corn was all gathered, the last wagon load, known as the Horkey Load, would be stacked high with sheaves and on top would sit the Harvest Lord, the reapers and a flower-crowned Queen (who I assume was the same Lady of Harvest as mentioned earlier. Decked with boughs and a straw figure made from the last sheaf, the load was drawn through the village and doused with pails of water by the villagers as a charm to conjure rain during the next growing season. The straw figure, spirit of the harvest, was kept until the following year to ensure a good yield once more.

The Horkey Supper was, of course, the highlight of the whole proceedings and must have been much on the minds of the reapers during the long working hours of the previous few weeks. It was provided by the farmer as part of the agreed terms for all those who had helped with the harvest, including the women who had tied and stacked the sheaves. Long trestles were set out and the company provided with roast beef - a rare luxury - vegetables, plum pudding and lashings of strong ale. The meal was concluded with many toasts; beer flowed and the drinking songs and games grew louder as the evening went on. The meal itself was followed by dancing and music, and at this time of year I like to imagine the imprint of all this revelry on every village green, ancient barn and inn that I pass.

A village I often find myself driving through here in north east Norfolk is Paston, which retains an enormous barn close to the road. I can see how it was the perfect setting for a Horkey Supper and there are records of it being used for exactly that. A long table was laid down the great length of the barn with the company divided by the great central tie beam (which, as an aside, I have actually seen. Although the barn isn’t generally open to the public to avoid disturbing the rare bat species that roost there, it was once the site of an art intervention that I visited.) After the meal the first song was greeted with the cry ‘Well done our side of the baulk’, which of course provoked the other side into a response. George Ewart Evans, chronicler of rural life, said that the phrase was still common in that part of the county in the 1960s. This was later confirmed by the folk singer Walter Pardon who lived in the neighbouring village of Knapton.

After the harvest the women and children were allowed onto the fields to collect up the remaining ears of corn - and this, I’m sure, would once have been happening right now as there are wasted ears to be seen round and about which no hungry family could have allowed to rot or be taken by crows and pigeons. This customary rite (and, indeed, a right) made a big difference to the cottage economy through the hard winter months. To ensure order and that everyone got their fair share, a Queen of the Gleaners was appointed, who, like the Lord of the Harvest, called the breaks by ringing a handbell. In some villages the beginning and end of the work day would be marked by the chiming of the church bell, called the ‘gleaning bell’. Now, that’s something I didn’t know and something else to dream of at this time of year when gazing at all those medieval church towers dotting the landscape.

In time, the Horkey Supper was replaced by the Harvest Festival with its theme of thanksgiving, and the customs and wilder excesses of the much older supper were tamed and smoothed out. Gone are the days when, as Nigel Pennick tells us in In Field and Fen, the Lincolnshire tradition of ‘The Old Sow’ was enacted at the harvest supper. The Sow was created by two men dressed in sacks, its head stuffed with cuttings from a furze (gorse) bush. It would suddenly appear at the feast and charge around the room, pricking as many people as it could reach and no doubt giving children nightmares that stayed with them all their lives.

Which, for good or ill - and with a slightly rueful glance back at the unbridled fun that’s been lost along the way - is where those tastefully designed posters on supermarket noticeboards come in.

Harvest from the cottage garden in my more organised days :-)

BAREFOOT

Barefoot, I thought, no that’s not me.

This summer I have hardly dipped

a bare toe in the sea foam.

Strange when I love the shore so much.

The scent, the squeak of pristine sand

the scurryings of turnstones in little gangs.

They have knees like us you know,

so they can run just as we do

even though their knees face backwards

or is it ours that are back to front?

Not many birds can bend at the knee

hardly any in fact.

A gentle soul I met on the beach told me that.

You learn a lot just by getting out there.

But back to barefoot.

I don’t go barefoot in the house even,

except when I slip out of bed at night.

I like my cosy socks.

Two pairs, actually, most of the year.

It was a single pair for weeks

but now it’s September which says it all.

I do remember going barefoot, yes.

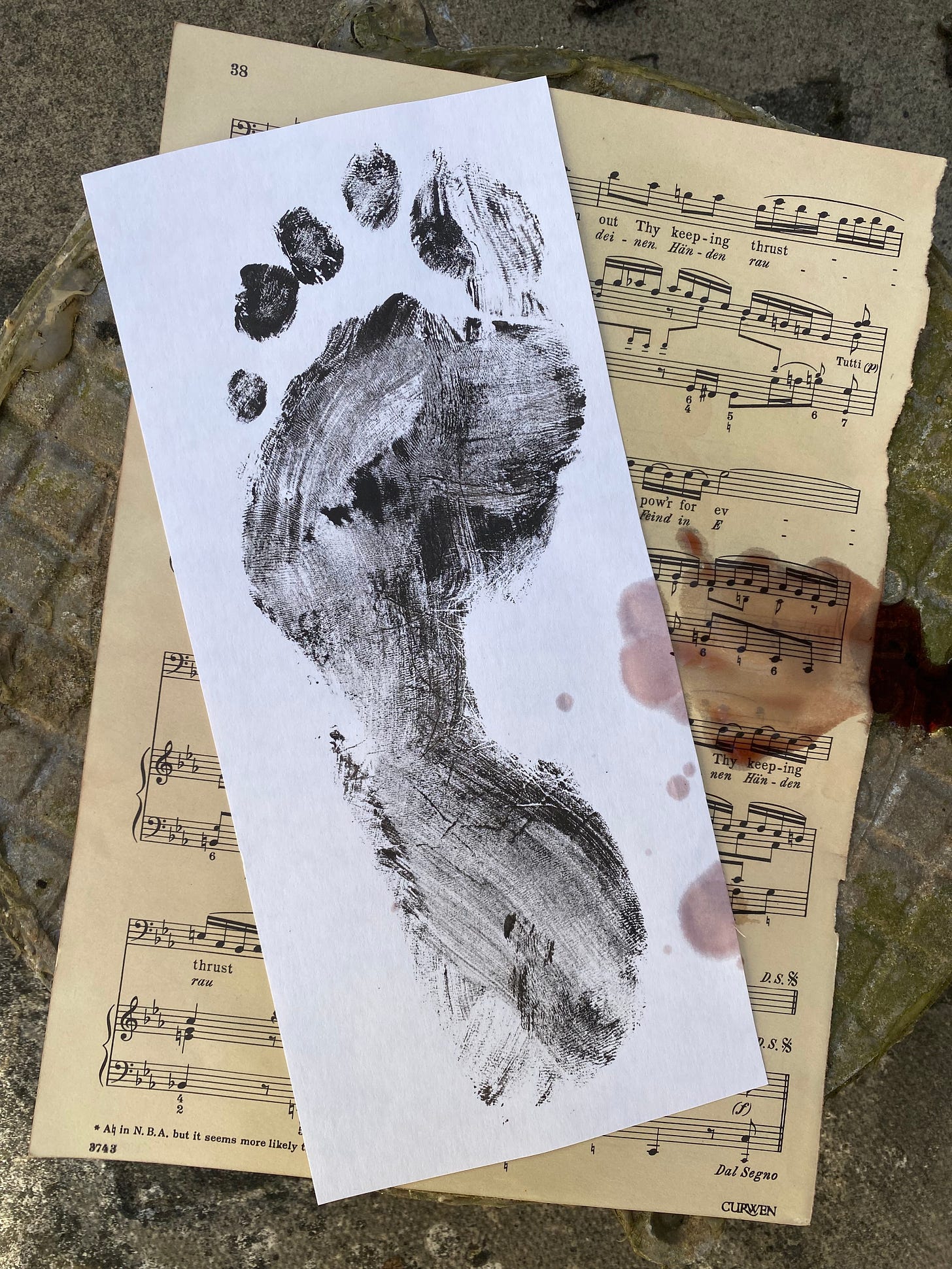

Sheets of church music and a dish of red wine

to stand in, dip my bare soles and toes

onto paper that was mute, yet held all the notes

in the universe. This is my blood.

I spread my toes on the staves,

strewed music like meadowsweet

over the torn carpet.

What can do more than blood and a tune

to tear your heart apart?

And then there are the ancient footprints

on top of the church tower, pressed into lead

where they might never be seen again.

Red wine may fade and blood be washed away

but not those feet and their music, not ever.

I couldn’t find any images of the art installation I made in a run-down Norwich shop front that’s referenced in the poem. It included a trail of my red-wine footprints on church sheet music stretching the length of the space. But I did find an old inked footprint of mine, some yellowing sheet music and a splash of red wine, so at least I tried :-)

LAYERS

You can see all the edges, smoothed and angled by the tides. I run my finger along the ridges, layer upon layer. Like a puff pastry pie crust, knocked up as my grandma would say. You held down the edge at intervals and then took the back of a knife to it over and over again. It was a job I loved to be given, standing on a chair in her Fenland kitchen. Then the layers would rise, and you would see all those edges. Yes, very much like that, although the oyster’s methods are more mysterious.

Does each layer represent a season in the sea? I would like to think so. A full turning of the year through winter storms and summer shallows filled with laughing splashing children.

The colours. Bleached and silky, deep glazed charcoal, chalky white and oh the pearl.

I don’t mean a small round precious thing, of course. I bet they kill the living creatures just for those. I mean the thin wash of moonlight that nature secretly brushes across the inside of each shell to infuse the oyster’s inner universe with beauty.

Although, obviously I know they get eaten. Swallowed down raw, is that it? A luxury now, once they were the food of the poor gathered by the bucket load. I can’t begrudge them that. And there was always a joy in the building of a shrine, the weaving of seaweed and the lighting of a candle. Each one a wonder, a lost land found.

Oh think of the colours then, as the flame flickered and turned the pearl to gold, and St James saw them, nodded his approval, granted benediction.

Oyster shells on the bedroom window sill (within sound of the sea), 18 September 2024

Well here we are at the cusp of autumn, and perhaps the nut-brown maiden has already tiptoed in if truth be told. The kitchen door is still left wide open all day, but every now and then the cry of wild geese sends me running outside to look up to the skies, where huge loose Vs proclaim the coming of Wild Hunt season.

Part of me, certainly, is resisting the turning of the wheel and the fading of those warm easy days of summer adventuring. How about you? Are you kicking against having to think about extra layers or looking forward to the time of cosy blankets and hot chocolate?

I’m still taking my cafetiere to the sea almost every morning before the day begins and it’s become something of an addiction so I had better be careful :-) But even more to be cherished are the occasional porridge-on-the-beach days, like the one pictured below that we had at Walcott last Friday.

So that’s me up to date - let me know in the comments how it is with you and whether you’re taking the nut-brown maiden by the hand or asking her to stay away for a while yet.

Breakfast provisions on Walcott sea wall, Norfolk, 13 September 2024

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

I really enjoyed reading this, thanks Imogen xxx

Those traditions are so fascinating and sorely missed I'm sure in this disconnected modern age. Thank you for your beautifully evocative words!