Winter thistle at Swanton Abbott, Norfolk, 1 December 2024

Hello and welcome to this new moon/early December edition of Bracken & Wrack.

The days are drawing towards their shortest; too dark to make it to the beach for early morning coffee and with a definite misty chill in the air from about 3.30 in the afternoon. Or sometimes earlier than that! But there is such beauty in those quicksilver hours of daylight that I can’t mind. The trick is to get out there and breathe the sweet musky air even as it sends shivers up your nostrils.

Sometimes I just walk to the end of the lane and back, and even that is always a joy. Perhaps a squirrel will squiggle across in front of me, or a sudden gust will send a fresh flurry of gold and bronze birch leaves dancing through the air. Often there’s the flick of a white upturned tail as a muntjac deer kicks up their hooves and darts into the bracken that’s fast dissolving before my eyes.

On the day of the last new moon, under pale grey skies and a light drizzle we stepped out from the shelter of pine, chestnut and sycamore to gaze across a field. Just an ordinary, much-ploughed, Norfolk field you might think. But this one is actually pretty extraordinary, and just a stone’s throw from home. Of course, it’s certain that tales sing out from under our feet wherever we roam in the landscape, but this field holds a particularly vivid and violent story.

It was here at this very spot that the rebels’ last act of resistance in the English Peasants’ Revolt (also known as the Great Uprising or Wat Tyler’s Rebellion) took place on 25 or 26 June 1381. Metal rang on metal and shouts, roars and screams pierced the summer air as the band of local peasants and yeomen fought with the blazing courage of their convictions. But armed only with the tools of their trade they could never be a match for the heavily resourced aristocratic forces of Henry le Despenser, Fighting Bishop of Norwich. The rebels were led by Geoffrey Litster, a dyer from the nearby village of Felmingham, who was captured and later suffered the terrible fate of being taken into the town of North Walsham to be hung, drawn and quartered.

The gently undulating field stretching before us is a poignant and nationally significant site, and I may be wrong but I have the feeling that very few of the town’s residents actually know it’s there. Which is all the more reason to stand quietly beside an old beech tree with its dips and hollows, offer our love to the rebels and leave a small gift for their leader who fought so passionately for the rights of the overlooked.

Beech on the boundary close to the battle site. It’s not old enough to have been standing when the rebels made their stand, but has its own stories to tell. 1 December 2024

But this unassuming acreage may just be about to become better known as the resonant and historically important site that it is. Excitingly, when I posted a captioned photo of the battlefield in my Instagram stories, I received a message from a writer who actually plans to write a play about the Battle of North Walsham. Although I think the playwright lives in Kent, she has links with a local professional theatre company who specialise in touring Norfolk and performing in unconventional venues. She’s said she will let me know if things take off and there could even be an opportunity for some sort of collaboration, so let’s see what happens.

All this is something of a digression from our overall theme for this edition of Bracken & Wrack, but before I tell you what’s planned this time, please allow me one more little rabbit-hole as I can’t resist sharing another seasonal Laurie Lee poem with you.

Laurie may have titled his haunting and fragile poem ‘November’, but for me it evokes the feeling of early December, which is why I wanted to include it in this edition of Bracken & Wrack. (Click below to hear an audio version of the poem.)

November loosens the tongue

like a leaf condemned,

and calls through the sharp blue air

a sad dance and a dread of winter.

The mistletoe reveals a star

in the dark crab-apple,

and chestnuts join their generations

under the spider sheets of cold.

I hear the branches snap their fingers

and solitary grasses crack,

I hear the forest open her dress

and the ravens rattle their icy wings.

I hear the girl beside me rock

the hammock of her blood

and breathe upon the bedroom walls

white dust of Christmas roses.

And I think; do you feel the snow,

love, in your crocus eyes,

do you watch from your trench of slumber

this blue dawn dripping on a thorn?

But she smiles with her warm mouth

in a dream of daisies,

and swings with the streaming birds

to chorus among the chimneys.

Laurie Lee, ‘November’

‘I hear the forest open her dress’ - intervention in the birches on St Lucy’s Day 2021

It’s not often that this rather mix-and-match newsletter has one discernible theme. Of course, I always hope it will evoke the moment in the season that it arrives in your inbox (if you subscribe, that is). But realising that the New Moon would this year fall during Andermas-tide (which for me means the 13 days after St Andrew’s feast day on 30 November) - ideas for this issue have been quietly shaping up ever since a conversation around a certain lake in early November triggered all sorts of memories and associations.

I’ll explain more in a moment, but first I’d better let you know that as my thoughts around the topic have expanded, so I’ve realised that this newsletter needs to be in two parts. I hope you won’t mind that I have shot off down this particular alleyway and find myself taking you all along for the ride :-)

Oh, by the way. If you’re someone who enjoys the Bracken & Wrack recipes, fingers crossed you’ll be a tiny bit mollified when I tell you that the two parts will have a recipe apiece which I hope you might like to try.

In Part One:

Shouts, Roars & Screams: the peasants’ last stand just a stone’s throw away

Seasonal Poetry by Laurie Lee

A Loch in Norfolk - Really?

Putting Food into Hungry Tummies: the appeal of Andrew

Wild Music: St Andrew’s Tin Can Band

St Andrew’s Dreaming Bannocks: a recipe and a charm

A LOCH IN NORFOLK - REALLY?

If you lived in Norfolk and being a Saturday volunteer at Loch Neaton ParkRun was suggested to you, you’d be forgiven for imagining that a surprise road trip to Scotland was on the cards. But strange to say, the Loch is actually far closer to home, albeit in a different part of the county. In fact, the name belongs to a large recreation ground and lake that’s described by the rather overlooked Norfolk market town of Watton as its ‘jewel’. And so it is.

Today the park is a green, leafy and well-used area for all kinds of sports and leisure activities. ‘Neaton’ is the name of a suburb of Watton so that part is easily explicable, but ‘Loch’?

Old jetty at Loch Neaton, Watton, Norfolk, 9 November 2024

An information board by the gates explains that Loch Neaton was created in around 1869 when earth was excavated for the building of a new embankment for the Bury and Thetford line during the height of railway expansion. When the quarry was filled in to create a fishing, boating and swimming lake it was, we’re told, named ‘Loch Neaton’ to honour the Scottish navvies (short for ‘navigators’) who dug out the earth to build the embankment. It must have been back breaking work and the recognition is well deserved. But still it’s an interesting turn of phrase, as despite the essential role they played in what was in Victorian times a very labour intensive exercise, the navvies weren’t always held in such high regard.

Digging cuttings and forming embankments, not to mention the construction of tunnels, bridges, viaducts, stations and goods yards, all required substantial numbers of men with a wide range of skills. Navvies moved with their families to work on engineering projects right across Britain. During the height of railway construction in the mid-nineteenth century, more than 250,000 navvies were employed throughout Britain.

The legacy of these travelling communities spreads snaking fingers right across Norfolk, even though most of the local lines were closed in the 1960s during the Beeching cuts. Today, many of those redundant trackways have been reclaimed by nature and turned into long distance walking, cycling and bridle paths including the wonderful Marriotts Way close to my old home in Reepham, and parts of the Weavers’ Way which is near our cottage between the heath and the sea.

Although many groups of navvies came from Ireland, and local men were also involved, it seems that most of those who worked on Norfolk’s railways were Scottish.

And THAT was my inspiration for this - and the next - edition of Bracken & Wrack :-)

Despite their massive contribution to our history through the building of the canal and railway systems, controversy and suspicion surrounded the groups of families wherever they went. Perhaps because of this, the navvies’ daily lives and experiences remain mysterious. Their social isolation and unsavoury reputation for being fierce, drunken, disruptive and ungodly creates an stereotypical image of the navvy that travelled with them and seems at odds with the wish of the people of Watton to ‘honour’ these men.

Reports of prize fights, gambling, petty crime, drunken sprees lasting several days, bad language, questionable conduct and general lawlessness are certainly not without substance, but then the navvies and their families lived very much as outlaws from society with landlords being reluctant to house them even where sufficient lodgings could be found. Many slept outside or in damp, insanitary huts, quickly constructed from whatever materials could be found just metres from the line itself. Missionaries who ventured fearfully into these shanty towns to ‘bring them to the light’ met with a mixed reception, although some navvy families took to the Sunday Schools, Mission Halls and charity provided by the church.

Generally, once a section of line or project was complete the navvies would move on to the next job, leaving the residue of their encampment as the only sign that they had ever been there. But one account I read, the blog of a Park runner called Ian, mentions that many of the Scottish labourers settled in the Watton area once the work on the railway was complete. And that would mean that they were not only accepted by the community, but that it’s likely that their descendants’ DNA mingles with that of indigenous Norfolk people to this day.

I haven’t been able to verify this, but it would be interesting given the other links between Norfolk and Scotland I’ve been following. For years I’ve been aware that the navvies who constructed the railway earthworks and buildings at Reepham were also Scottish, so the mystery deepens.

Young ash trees along Marriotts Way, the disused railway line near Reepham, Norfolk. Much of the work here was done by Scottish navvies. In their day no trees or other vegetation would have been allowed anywhere near the line for fear of fire caused by sparks from the coal-powered steam trains.

PUTTING FOOD INTO HUNGRY TUMMIES: The appeal of Andrew

Fishing boat with Scottish flag: embroidered kneeler in St Andrew’s Church, Hempstead, Norfolk, 3 December 2024

In my recent essay St Catherine & the Wild Woman I mentioned that I was actually born into a home address containing not one but TWO saints’ names. While still very young I learned to write these names and reel them both off without really having to think about they meant at all. St Catherine might have overseen the quiet road of suburban semis where I first opened my eyes, but it was St Andrew who held the guardianship of the parish itself. Nestled by the River Yare and almost touching the city of Norwich, there’s no real indication of why that particular dedication was chosen for its medieval church.

As one of the original twelve apostles - in fact the first to be called to become a ‘fisher of men’ St Andrew was a popular saint in any case. But Andrew was a fisherman by trade, and I would conjecture that in this county of rivers, Broads and a long, long coastline his association with fishing had something to do with the regularity with which his name can be seen on churchyard noticeboards.

In Earth Magic: a wise woman’s guide to herbal, astrological and other folk remedies, Claire Nahmad reminds us that Andrew attended and helped at the feeding of the five thousand, a miracle whereby five loaves and two fishes magically ‘stretched’ to allow everyone in the crowd to feast together. A saint who looked after fishermen and had participated in an act that put food into hungry tummies might well have had special appeal during the many hard years of plague, drought and famine.

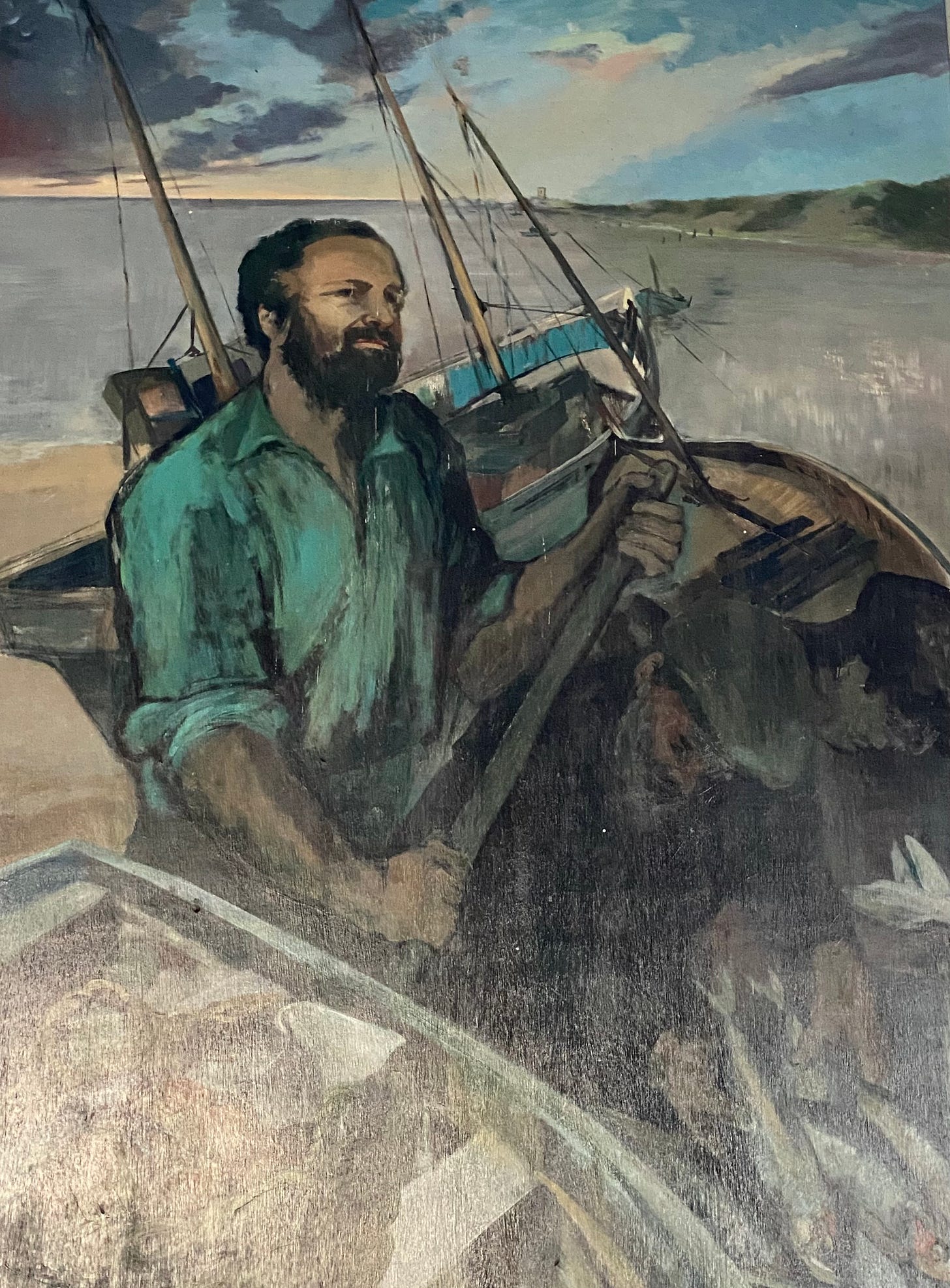

Andrew and his brother Simon Peter in their fishing boat, stained glass in Edgefield church, Norfolk

We’ll come back to Andrew’s association with the sea, but another observation of Claire Nahmad’s also rang a bell with me. Andrew is Greek for ‘a man’, especially one of simple, powerful, magnetic and spiritual qualities. These qualities are applicable to what we know of St Andrew, and are, she says, ‘also virtues generally beloved and esteemed by the Scots; this might be part of the explanation as to why he was chosen as their patron saint.’

Could it also be part of the reason that Andrew appealed to the down to earth people of Norfolk?

This modern painting of Andrew hangs in St Andrew’s church, Hempstead. Glare from the window opposite made it impossible to photograph well but hopefully you can make out the basket of fish and bread on the lower left, and there’s definitely a sense of no-nonsense physicality - 3 December 2024

Although Andrew himself never set foot in Scotland - unlike some of the other countries of whom he is patron saint - a number of his relics are said to have been brought to that land, where they remain to this day. How this came about is the stuff of legend (as you might expect) and there is more than one story in circulation. This is St Andrew’s University’s version of the tale:

After Andrew was crucified on an X-shaped cross for spreading Jesus’ teachings in around 70 CE, his remains were taken to Patras in Greece. One of the monks there, St Regulus (also known as St Rule), had a dream in which he was told to hide some of the bones. Then, around 357, on the orders of the Holy Roman Emperor Constanius II the relics were moved to Constantinople [now Istanbul] to rest in the Church of the Holy Apostles.

St Regulus then had a second dream in which he was told by an angel to take some of the bones to ‘the ends of the earth’ to protect them, and that he should build a shrine there. He set off taking a kneecap, an upper arm bone, three fingers and a tooth from St Andrew to find a safe place for them.

His journey however did not go smoothly. St Rule was shipwrecked off the coast of Fife in Scotland, but fortunately he was able to deliver the relics to Kilrymont on the East Fife coast, a centre that was already sacred to the Celtic church.

Kilrymont is now known as St Andrew’s. And true to his vision, St Rule established a shrine for the saint’s bones at the place where St Andrew’s Cathedral now sits.

Charles Babalola (L) as St Andrew, with his brother Simon Peter, in the 2019 film ‘Mary Magdalene’.

WILD MUSIC: Andrew’s Tin Can Band

As Scotland’s patron saint, naturally St Andrew’s Day - Andermas - is celebrated in a big way in that country. Games, music, feasting, storytelling - all of these are traditional on 30 November and an ‘Andermass Medieval Fair’ takes place each year on the streets of Perth.

Around the world, too, I found snippets of lore relating to St Andrew’s Day customs and magical practices. But given that I wanted to explore the deeper connections between Scotland and this - on the face of it - very different landscape here in Norfolk, I began looking for St Andrew traditions in England. These, I thought, might act as a bridge between the two lands and perhaps offer some kind of clue.

And, although I didn’t find much to go on, the tradition that did come up was very interesting to me, as it draws on deep memory of Julian Calendar time and tide as well as echoes of other folkloric practices.

In Charming The Fields I wrote about the Rogationtide custom whereby villagers would ‘beat the bounds’ of a parish three times, making lots of noise on pots, pans, buckets - whatever they could lay their hands on - to scare away the demons that caused famine, plague and other ills and send them over the boundary into the next parish instead. Charming indeed :-) And the Andermas custom that takes place annually in the village of Broughton in Northamptonshire (not far beyond East Anglia) is very reminiscent of this.

For one thing, my ears pricked up to hear that the church in that village is another St Andrew’s. Not surprising, then, that the parish honours the saint’s feast day. Except, that most parishes with a St Andrew’s church - including the many in Norfolk - don’t really go to town in this way even though the date in the dark part of the year leading up to the midwinter solstice might have inspired old traditions of Molly Dancing or other annual celebrations.

But here’s the thing. The people of Broughton have marked Andermas-tide for at least 300 years with a Tin Can Band tradition that, with its banging of pots, pans, spoons, dustbin lids and spanners bears more than a passing resemblance to those Rogationtide processions of old. The start of the controversial - even infamous - event just before midnight is actually blessed by the vicar of St Andrew’s.

Now, you might expect the Tin Can Band to strike up on at dead of night on St Andrew’s Eve (29 November), heading into the morning of the saint’s feast day. Excitingly though, each year the event takes place on the first Sunday night/Monday morning after 12 December (Old St Andrew’s Eve), which, as readers of Bracken & Wrack will know, means that it has been set according to memory of how the season ‘felt’ in the days when the Julian calendar marked the turning of the year. So it truly is an old tradition, and I do wonder how many more now-lost versions of this spectacle might remain unrecorded.

You can watch a short clip of the procession here

ST ANDREW’S DREAMING BANNOCKS

‘On the twenty-ninth day of November, which is St Andrew’s Eve, it is a treat to make ‘dreaming bannocks’. The recipe is Scottish and the bannocks are very good.

Take a generous portion of eggs and flour and best butter, enough to bake cakes for all the company, mix well together and put in plenty of salt and a dash of cinnamon. Then for each separate cake you must add a tiny pinch of soot, hardly bigger than a pinhead. Bless the cakes as you form them out of the dough and toast them well on the grid-iron; but this must be done silently, for it is said that the baker must be as mute as a stone while baking and toasting, for one word would destroy the whole concern.

Give one or more of the cakes to those who are trying the spell with you, and save a couple for your own supper morsel. Then must you all retire to bed in perfect silence, where you will be sure to fall into slumber and see wonderful emblems of your destiny.’

Bannocks are traditional Scottish griddle cakes and luckily for us, our Victorian Yorkshire Wise Woman gives a charm (and a very imprecise recipe!) to be essayed on St Andrew’s Eve. Now, you might like to wait until next year to try this, or like me you might be happy to see the Tide as stretching right up until Old St Andrew’s Day, meaning that the night of 12 December would be the one to choose.

The first challenge, though, is converting the recipe into something that might hold together as a griddle-cake, and not content with this I also want them to be vegan. (Obviously you can adapt them again if you’re not.) This is what I have come up with. They are very plain as no sugar is involved - this they have in common with traditional Norfolk Rusks, the recipe for which will crop up here very soon :-)

Unlike Welsh Cakes, clearly it’s not traditional to add currants either, so they will be best served immediately, warm from the griddle (or heavy based frying pan) with some spread, vegan ‘butter’ or a drizzle of olive oil.

225g plain flour

1 tsp baking powder

75g vegan block (‘butter’)

1 teasp cinnamon

1 teasp cardamom (optional but helpful as the recipe lacks the true butter flavour)

1 teasp sea salt

1 tbsp plant-based yoghurt + 2 tsp wine vinegar or lemon juice (replaces egg)

Dash of plant-based milk to mix to a shapeable dough (go gently on this)

Tiny pinch of wood-ash per cake (very much optional - I’m sure they will still be effective without. It’s the intent that counts)

Mix flour, baking powder, cinnamon, salt and optional cardamom.

Rub in the vegan block and mix in yoghurt, vinegar/lemon juice and a little milk to form a soft but not sticky dough.

Shape into small flat cakes and press a tiny pinch of soot or ash into each (optional and at your own risk).

Heat a griddle or heavy pan and smear with a little vegan block or oil to prevent sticking, then cook on each side until nicely browned. Making the cakes small and flat will help them cook evenly right through.

If you try the spell as written, let me know how it goes!

St Andrew on the medieval rood screen at nearby All Saints’ church, Edingthorpe, Norfolk

Until next time.

With love, Imogen x

Wordsmithery right there💚 Thank you x🙏🏻